Brantford in the 1980s - Post 22

The 1980s saw significant changes in the downtown. New developments designed to reinvigorate the downtown totalled $50 million. Yet, as much as there were new developments some things did not change. Downtown Colborne Street continued to see an exodus of businesses. and the buildings continued to deteriorate due to the lack of enforcement of property standards. In spite of all the investment downtown residents largely stayed away; they did not venture downtown.

Downtown

Development of the Market Square seemed imminent when Campeau Corporation and the T. Eaton Company agreed to a partnership to redevelop the property. The plan included an Eaton’s store at the east end of the development, a 550-space parking garage, retail stores, and a 300-space parking garage at the corner of Colborne and Bain Streets with a skywalk to the Eaton’s store. The province agreed to a $6.4 million loan for the project in January-1980. The provincial loan was contingent on a signed agreement between the City and Campeau by 30-April. However, the development would be plagued with delays.

Market Square 1980. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Before an agreement could be signed, all the necessary property for the redevelopment would have to be assembled. Acquiring the land proved problematic because downtown merchants who owned property required for the development were not all supportive of the development. City Council would not pursue expropriation as an avenue to solve the impasse. The City was reluctant to close George Street but Eaton’s was adamant that it wanted to build on this roadway, in order to be directly connected to the mall. This was a deal breaker for Eaton’s. The new development required the downtown plan to be amended and resubmitted to the Ontario Municipal Board for approval. Remember, all these things needed to be accomplished in four months to be eligible for the government loan.

George Street store fronts 1980. These building were demolished, and the businesses relocated, to make way for the Eaton Market Square Mall development. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

In June, Campeau announced that it was unable to attract a supermarket to the development. In October, Eaton’s pulled out of the development as a partner but agreed to remain as a tenant. The City requested another extension of the provincial loan guarantee. In December, Eaton’s threatened to withdraw from the development entirely if the proposed expansion of the Brantford Mall, which included a major department store, was approved by Brantford Township. The City intervened with the Minister of Housing implementing a partial freeze on the Brantford Mall development.

On 1-January- 1981, the City would annex Greenbrier and Wyndham Hills from Brantford Township which included the Brantford Mall. On 29-December-1980, Brantford Township issued building permits for the expansion of the Brantford Mall. The City immediately passed a bylaw in early 1981 to limit any development at the Mall site. The Mall launched a court action against the City to rescind the bylaw. The parties settled the issue in February-1982 when the City allowed expansion to proceed with the proviso that the Mall not apply for a building permit until 1-July-1983 or until the foundation of the downtown development was in place.

Meanwhile, negotiations between Campeau and the City dragged on. Settlement with property owners along George Street still had to be reached. Campeau needed an extension to conduct soil tests, complete its agreement with Eaton’s, and find retail tenants for the mall. The City asked the provincial government for an increase to the loan guarantee; the province agreed to increase the loan to $7.4 million.

The downtown development plans would change again. The parking garages would be combined into one structure, a mini-mall would be constructed at Colborne and Bain Streets to house the displaced merchants from George Street, and Market Street would be closed between Colborne and Dalhousie Streets to be replaced by a pedestrian walkway.

On 20-July-1981, a formal agreement between the City, Campeau, and Eaton’s was signed. Eaton’s agreed to operate their store for at least 35 years and Campeau posted a $500,000 letter of credit against the company withdrawing from the project.

In October-1982 Campeau asked for a one-year extension to begin the project. The company was having difficulty signing tenants for the property and the economy was poor, so mortgage money was not available. The City granted Campeau an extension to June-1984.

The delays only added to the cost of the project. Rumours swirled that Eaton’s was ready to pull out. The province contributed another $2 million to the project.

On 29-June-1984, a settlement was reached between the City and Campeau clearing the way for the development of Market Square to begin. The cost of the development was now estimated to be $37 million. The cost to the City increased by $3.4 million. This included a loan to Campeau for a public space inside the mall, and the relocation of services on Market Street. A sod turning ceremony was held in April-1985.

Construction of the Eaton Market Square from the same point of the view as the 1980 photo. Note the newly opened Becket Building just to the right of centre. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Work on the $12 million parking garage was delayed. Scheduled to open in 1985, the parking garage was not completed until June-1986. The contract for the structure was awarded to a local company, Sternson Ltd. Within a month of opening blistering occurred on the top deck and the floor had to be resurfaced.

Construction of the parking garage looking towards the Farmers’ Market. (photo by J. Miklos, courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Construction of the parking garage looking down Market Street South along the sightline of the former Victoria Bridge. (photo by J. Miklos, courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

The Eaton Market Square Mall formally opened on 19-August-1986. 1,500 guests were invited to the opening. The Expositor marked the occasion by writing …the opening of a bright new era in the long history of the city’s core area.

Market Centre Parkade Grand Opening, Friday 27-June-1986. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Other efforts were initiated to increase the appeal and traffic downtown. The downtown was rebranded as City Centre, complete with a mascot, Seemore. A walk of fame was established on the west side of the Pauwel’s Travel Centre Building, next to the Dalhousie Street parking lot that featured the portraits of Joseph Brant, Alexander Graham Bell, Pauline Johnson, Jay Silverheels, and Wayne Gretzky. These portraits were painted by Hendrik Lenis and Wayne Phillips.

Seemore, Downtown Brantford mascot. (photo courtesy of the Downtown Brantford BIA)

The Richard Beckett Building opened at the corner of Colborne and Bain Streets in 1985. Beckett was the mayor of Brantford between 1961 and 1970. The building contained a downtown campus of Mohawk College, offices, a senior citizens’ drop-in centre, and 63 low cost apartments for seniors. It was hoped that the building would spur further development of residential living downtown.

Demolition of the former Bank of Nova Scotia building at the corner of Colborne and Market Streets occurred in November-1985 to clear the land for the construction of Massey House, a six-storey office building, by Campeau. The building was to house the offices of Massey Combines Corporation. The company moved into their new offices in December-1986 and filed for bankruptcy in March-1987. Massey was replaced by the Holstein Association of Canada. The building was renamed Holstein Place.

Bank of Nova Scotia and Keachie buildings at the south west corner of Colborne and Market Streets. Originally the site of the Bank of Hamilton. The Bank of Hamilton merged with the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 1924. The bank of Nova Scotia was located in this building until the bank moved into their new branch across the street in 1980. (photo by J Miklos, courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Massey House is built on the site of the Bank of Nova Scotia building, Keachie building, and the Belmont Hotel. Massey Combines Corporation moved their head office here in December-1986, four months before they filed for bankruptcy. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

In 1986, construction began on Darling Court on Darling and Queen Streets which houses provincial government services. It opened in 1987.

Three proposals that never came to fruition:

Renaissance Place was to be a retail and apartment project in the Arcade Building at Colborne and Queen Streets;

River Heights, an 18-storey condominium tower, proposed by the Canadian Order of Foresters Insurance Company, on Brant Avenue overlooking the river;

A 15-storey Constellation Hotel to be built were the Royal Bank building is today at the corner of Brant Avenue and Colborne Street. The Best View Hotel was purchased by the City and demolished to make way for this anchor development at the west end of the downtown.

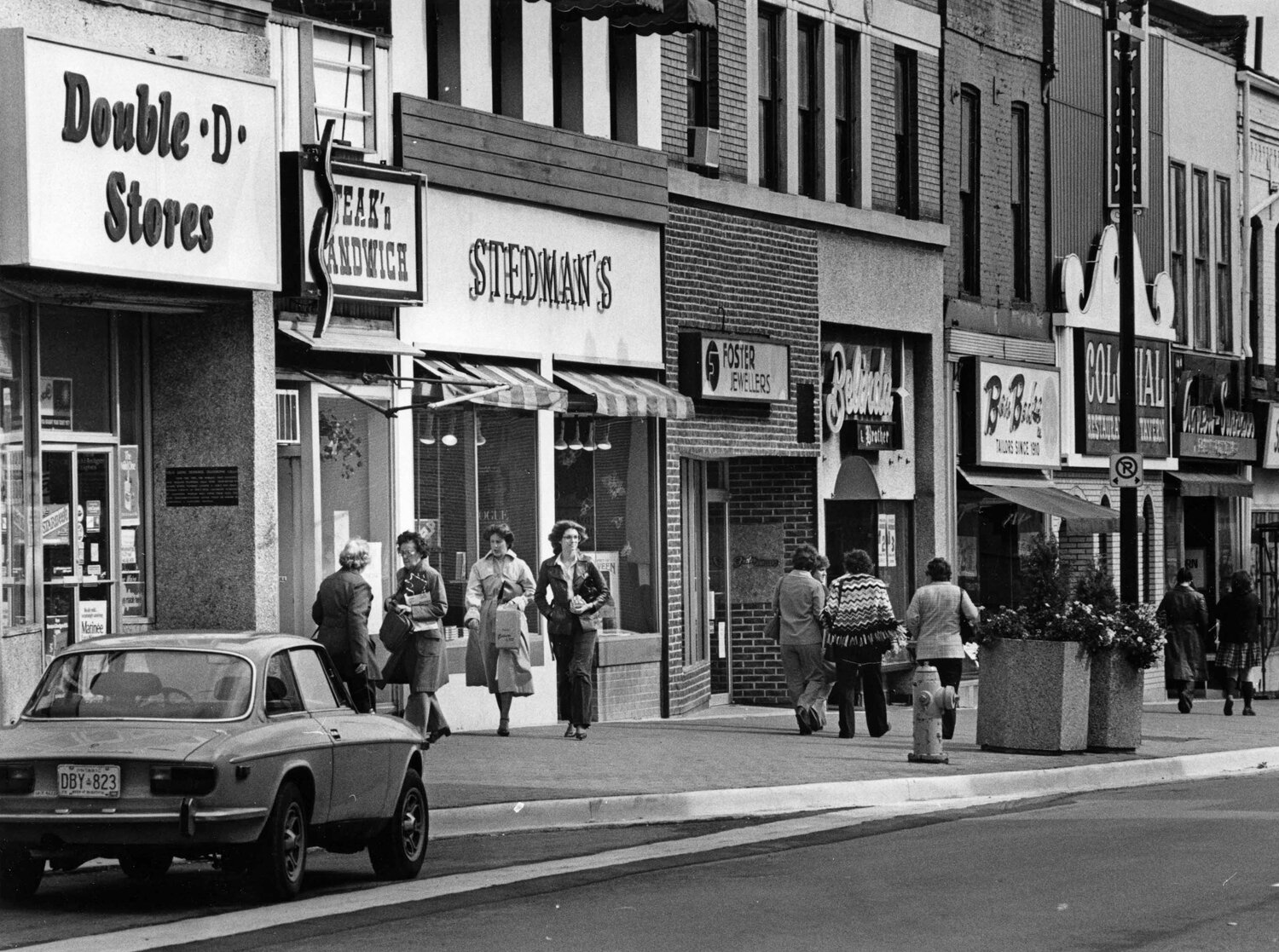

In spite of the new developments and marketing initiatives to get people downtown, the downtown continued to deteriorate. The old buildings along Colborne Street were not well maintained and businesses continued to close, even long-established businesses like Stedman’s Book Store. Citizens outside the downtown area were no longer comfortable visiting the downtown. These conditions led to the demise of the proposals mentioned above.

Stedman’s Bookstore and other businesses along the north side of Colborne Street in the early 1980s. Stedman’s was a long time fixture in downtown Brantford in the 20th-century. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Development of the Market Square posed a dilemma for the chip wagons stationed at the Square. Zoning bylaws did not allow for their relocation anywhere else in the City. The downtown chip wagons were a Brantford institution dating back to the late 1940s. In 1981, the chip wagons were voted Canada’s best french fries by Weekend Magazine. A public meeting was required to decide the fate of a temporary bylaw to save the chip wagons. The Expositor noted: Only in Brantford do you get public meetings on the subject of french fries.

The synchronisation of the downtown traffic lights continued to elicit angry responses from the motoring public. This had been an issue since the introduction of one-way streets in 1954. In 1981, the City took part in an experimental computerised traffic light system sponsored by the Ministry of Transportation. The system cost $630,000 to implement. In 1983 the system was still not operational. Another two years passed when a consultant finally determined that the City did not assign sufficient staff to operate and manage the system, and as a cost savings measure the City purchased electrical-mechanical controllers rather than solid-state controllers. Municipalities that installed the solid-state controllers experienced few problems.

Was downtown Brantford in a better state by the end of the decade than it was going into the 1980s? According to a local downtown merchant, the turning point for downtown came in 1979 when the sidewalks on Colborne Street between Queen and Market Streets were widen and the number of parking spaces reduced. Up to this point all the commercial store fronts were occupied. With reduced easy access on-street parking, the number of visitors to downtown declined. The planned work between King and Queen Streets was cancelled because of store owner outrage. Even after millions of dollars were spent on new developments, the bulk of the downtown still contained old 19th-century buildings that were poorly maintained which, when empty, did not create a safe and welcoming environment.

Brantford Downtown 1984. An aerial photograph of downtown Brantford. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

A - The site of the Darling Court courthouse.

B - The site of the Brantford Transit terminal.

C - The site of Eaton’s Market Square Mall.

D - Beckett Building

E - Construction of the parking garage.

F - The Ring Road, now known of Icomm Drive.

G - Timberjack, formerly Koehring-Waterous, now the site of Brantford Commons and the Fresh Co. grocery store.

H - Best View hotel, now the site of the Royal Bank of Canada building.

I - Bridge Street. This portion was closed when the Ring Road opened and the Brant Avenue / Colborne Street intersection was reconfigured.

Brantford Downtown 1986. An aerial photograph showing the completed Eaton’s Market Square Mall and Parking Garage. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

The Circus - Popular for a time in the 1980s, this restaurant was located at 175 Dalhousie Street. The building was demolished in 1994. Phoenix Place Apartments now occupies this site. (image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Transit Terminal

I am amazed at the hurdles a municipality can put itself through when it tries to make the right decision and satisfy the demands of multiple constituents with conflicting needs. Politics always complicates the process. With the proposed developments contemplated for downtown renewal, a search began for the site of a new transit terminal. Little did anyone think this task would take nearly ten years. The development of the Market Square along with the closure of Market Street between Colborne and Dalhousie Streets required a new municipal bus transfer site. In 1984, the Public Utilities Commission selected the municipally-owned parking lot at Dalhousie and King Streets as a temporary transfer location for its terminal but downtown merchants did not want to lose the parking spaces so it was back to the drawing board. City staff proposed to close Queen Street between Darling and Dalhousie Streets and purchase the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce building to use as a terminal building. This solution was opposed by the YM-YWCA as the pollution from the buses and traffic congestion was not compatible with the operation of a fitness facility. City Council then selected the north side of Dalhousie Street between George and Market Streets but this was immediately rejected by the PUC as unworkable.

Transit Terminal 1934, Market Square, corner of Colborne and Market Streets. This terminal was demolished in the mid-1960s. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

The deadline to find a location, 1-January-1985, came and went. There was only one thing left to do: set up a committee of course. Representatives from the PUC, City Council, the Business Improvement Area, and Campeau Corporation began another search. Twelve sites were studied and two were selected. The committee selected the Dalhousie Street parking lot across from the Sanderson Centre (now the location of Harmony Square) and Council approved the location, but the BIA lobbied hard against this site and in March-1986 Council withdrew its approval. A new committee was struck, this time with more Councillors, In July, the PUC and technical City staff recommended the Dalhousie and King Streets parking lot as the best location to encourage downtown revitalisation. However, this site meant the acquisition and demolition of heritage buildings forcing businesses in those buildings to relocate. The parking lot itself was too small to accommodate future expansion and would require a terminal redesign. For these reasons this site was rejected by City Council in February-1987. The search was still on.

Bus Barns 1962. Corner of Brant and St. Paul Avenues. This facility opened in 1906 and housed the street railway cars. The last street car made its final run on 31-January-1940. The facility was converted to a garage for the buses. In 1970 a new bus service facility opened in Holmedale and this garage closed. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

In June, the property behind the Canada Trust building on Darling Street, the former site of the Forbes Bros. GM dealership was selected and approved by City Council and the PUC. The delays saw the price of the terminal building increase by $100,000. The new terminal finally opened on 20-September-1988.

Transit Terminal present day.

Capitol Theatre

The City had been lobbied for years by the arts and culture community for a performing arts space. This would be an important addition to the community in its civic renewal efforts. The market for cinemas was changing from one of a large theatre with a gigantic screen to multiplexes, facilities that housed multiple small intimate theatres in one complex. Famous Players had contemplated chopping up the cavernous Capitol Theatre into several small theatres, forever destroying the interior of the theatre building. Campeau planned to build a multiplex in their Market Square development and was trying to lure Famous Players, the owners of the Capitol Theatre, to move their operations to the new mall. When Famous Players agreed, the Capitol Theatre was surplus to their needs and was offered to the City for $425,000. The City would have its performing arts centre.

Capitol Theatre. Designed by famous theatre architect Thomas Lamb of New York, who also designed the Pantages, Elgin, and Winter Garden Theatres in Toronto, for the Brantford Amusement Company and built at a cost of $350,000. The theatre opened on 22-Dec-1919. Originally called the Temple Theatre in recognition of the adjoining Temple Building. In 1929 Famous Players purchased the theatre and made it one of the first theatres in Ontario wired for sound. The name was changed to Capital Theatre in 1931. The last film at the Capital Theatre was screened on Thursday 21-Aug-1986. The City of Brantford purchased the theatre in 1986. On 11-Dec-1989 the theatre was renamed the Sanderson Centre for the Performing Arts. In 1990 the theatre underwent a $2 million restoration. The theatre seats 1,133. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Capitol Theatre undergoing restoration in 1990. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

The theatre closed its doors on 21-August-1986 and the City concluded its purchase of the building in October-1986. Market studies indicated that the theatre would need to operate on a subsidised basis for between $100,000 and $200,000 a year, yet the City pressed on, hiring a manager. The first production presented at the City’s new performing arts space was the musical Evita, in October-1986. The production was a success. However, a consultant’s report released in November identified $4.2 million in needed repairs and upgrades. The first-year box office results were disappointing. A report noted that the theatre suffered from poor planning and organisation. The theatre needed better financial controls. A new name for the facility was also recommended to distance the theatre from its movie palace past.

A new marquee and lobby were completed in 1988. Brantford-raised Hagood Hardy was a featured performer in 1988. The theatre was closed in October-1989 to undergo a complete restoration of the auditorium, to return it to its 1920s splendour.

The Sanderson Foundation, founded by the wife of Brantford industrialist John Sanderson, donated $500,000 towards the restoration of the theatre. On 11-December-1989, City Council during an in-camera session decided to rename the facility The Sanderson Centre for the Performing Arts. This was a contentious issue because the decision was made in-camera and the Sanderson Foundation attached no conditions to its gift.

John Sanderson

John Sanderson (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

John Sanderson’s father Henry, arrived in Brantford in 1831 with his parents, from Lancashire, England. Brantford was a small village of 350 people at the time. Henry built a successful farming operation on Paris Road. His oldest boy John was born on the farm in 1857. John had a head for business. He joined Adams and Son, a wagon manufacturing company in Paris in 1886. As the firm grew, John quickly rose in the ranks of the company becoming a partner in 1892. In 1900, the company was reorganised and became the Adams Wagon Company and moved to Mohawk and Greenwich Streets in Brantford, with John as President. The new factory was the most modern in Brantford boasting an assembly line. In the early 1890’s, the Sanderson’s bought and moved into the Bell Homestead. John’s business interests expanded, and he sat on the boards of many local companies. John’s success continued, and he moved his family to a grand home at 74 Dufferin Avenue. John died suddenly on 14-March-1917 due to complications from diabetes. John’s estate passed to his wife Emily after his death and then to their two unmarried daughters after Emily’s death in 1937. The foundation set up by the family continues its support of church mission work and city causes to this day.

International Telecommunications Discovery Centre

A telecommunications museum was to be a major City altering development. Initial projections estimated that the museum would attract 350,000 visitors a year after five years. This was later revised to 700,000 visitors per year after five years. The telecommunications industry showed little enthusiasm for the project but the community was solidly behind the project. A 1982 report deemed that the museum was feasible and laid out what needed to be done regarding the marketing of the facility, the fundraising necessary, and the cost of construction and operation.

In 1983, the City selected the site of the former Scarfe factory on the Ring Road (now named ICOMM Drive) for the location of the museum. The building built for the museum is now the Brantford Casino. The CNR rail line separating the Scarfe property from the former Massey-Harris property was relocated and the CNR bridge was repurposed to carry a new water main across the river. The museum was expected to be open by 1987.

Scarfe Paints complex, 1920s., 31 - 35 Greenwich Street. Originally called Brantford Varnish Works & Company. William J. Scarfe purchased an interest in a Windsor, Ontario varnish works in 1877 and moved the company to Brantford in 1878. The factory on Greenwich Street opened in 1885. The company was family run until it was sold to Rinshed Mason Ltd. Inmont Canada Ltd bought the plant in the 1960s from Rinshed Mason of Canada Ltd. The plant on Greenwich Street was closed on 1-June-1977 and the business opened its new location at 10 Craig St on 19-July-1977. The Greenwich Street plant was demolished in 1978. Inmont Canada became known as BASF Inmont Canada in the mid-1980s. The company closed its Craig Street plant in December-1996. The Brantford Casino, built as ICOMM, is located on the site of the former Scarfe factory. (photos courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Scarfe Paints office.

Scarfe Paints billboard.

In 1985, the cost of the museum was estimated at $20 million. The provincial government pledged $5.5 million towards the project contingent on matching federal funds which were pledged in 1986. The City was expected to contribute $1 million. Fundraising would make up the difference. The opening date had slid to 1990.

The museum, to be known as the International Telecommunications Discovery Centre, was to consist of three modules. One module would focus on the history of telecommunications, drawing heavily from the Bell Canada collection of artefacts. The second module, called Telecom 2020, was to be a science centre type discovery centre focusing on commercial applications of future technology. The third module, the Canadian International Telecommunications Institute, would be used by technology companies to create cooperative development programmes. It was hoped that the Institute would be the catalyst to draw technology firms to the City and help diversify the local economy creating high paying research and development positions.

The sod-turning for the museum building occurred on 16-June-1989. The opening date was now 1991 and, of course, the cost of the project continued to increase. Those increases would have to be borne by the City and the fundraisers.

Civic Matters

Derek Blackburn of the New Democratic Party was Brantford’s elected member of Parliament for the whole decade. Derek was first elected in 1971.

Phil Gillies of the Progressive Conservative Party represented Brantford at the Ontario Legislature between 1981 and 1987. He was defeated in the 1987 election by David Neumann, Brantford’s mayor at the time, running under the Liberal Party banner. In 1985, the Progressive Conservatives, who held power since 1943, were replaced by a Liberal / NDP coalition.

Phil Gillies, Charlene Nicholson, parliamentary assistant, Cheri Smith, office manager, 1986. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

David Neumann, an alderman since 1976, defeated incumbent Charles Bowen in the mayoralty race of 1980. Neumann served as mayor until 1987 when he was elected MPP for Brantford. Rather than conducting a by-election City Council appointed Karen George as mayor. George was Brantford’s first female mayor.

City Council for the three year term 1986 to 1988. David Neumann was elected to the Ontario Legislature in 1987. Karen George was appointed Mayor by the City Councillors to fulfill the role for the remainder of the term. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Charles Ward, known as Charlie to his friends, passed away in 1982 at the age of 90. A local icon, he served as an alderman for all but two years since first being elected in 1952. At the time of his passing Ward was the oldest holder of an elected office in Canada.

As the 1970s ended, the City again needed to expand in order to accommodate population growth. Annexation talks commenced with Brantford Township in 1979. After six months of negotiations, in April-1980, the two sides came to terms. The City would annex 4,660 acres of Brantford Township land, which happened to include one-third of its population. The City agreed not to seek annexation of Township lands for at least 23 years, and the Township agreed not to develop lands along its border with the City. With this agreement, any idea of regional government in this area ended.

In 1980, the City hired a Chief Administrative Officer so that City Council could focus on policy setting and reduce the time it spent on administrative matters. The term of the mayor and aldermen was extended to three years, from two, in 1982.

According to a 1980 consultant’s report, leadership at City Hall was lacking. This lead to citizen apathy. The City needed to engage with its the residents and market what the City had to offer. The City needed an image makeover. In 1984, the Let’s Speak Up campaign was launched to boost Brantford’s image locally. The campaign was supported by advertisements, media releases, and a theme song.

Let’s Speak Up record. This campaign was designed to boost civic pride in the City. The campaign was supported by advertisements, media releases, and a theme song. Other cities were conducting similar campaigns, among them Hamilton and Buffalo, NY. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

A 1979 report outlined the inadequacies of the Brantford’s Public Library system, remarking they were housed in cramped quarters in the Carnegie Building, that opened in 1904. The Library Board was asking for a new building, ideally located on the southwest corner of Colborne and Market Streets, the busiest intersection in the City. The Forbes Brothers property on Darling and Queen Streets was recommended but a failure to secure a Wintario grant scuttled plans for this project. A new library languished on the City’s capital projects priority list. Suddenly in 1989, the City announced it would purchase the Woolco store at the southeast corner of Colborne and Market Streets and convert the building into a new library. It was hoped that the library would serve as a traffic generator for the downtown.

The Lorne Dam had long been deteriorating. A 1982 report declared that given the advanced state of deterioration the dam needed to be either repaired, replaced, or removed. No action was taken. Finally in 1989, on the advice of Grand River Conservation Authority, the dam was removed.

Lorne Dam 1984. The photograph shows the state of deterioration of the dam. The dam was removed in 1989. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Tipping fees, a fee to dump garbage at the municipal landfill site, were introduced at the Brantford landfill site in 1981. A one-year trial project for a recycling programme was launched in 1986. The programme continued beyond the trial period due to strong public support.

The issue of Sunday store openings was raised in 1986 and 1988. Surveys and a non-binding referendum showed that the residents were against Sunday store openings by a margin of three to one.

An interagency council on smoking and health asked City Council to create a bylaw to prohibit smoking in public areas. The issue of prohibiting smoking in public buildings was rejected by City Council in 1977. In 1986, the Public Board of Education banned smoking in all its buildings. City Council then followed suit with a smoking ban in public places.

In 1982, the Brant Multicultural and Citizenship Council merged with the International Villages Festival committee to form the Brantford Ethnic Festival and Cultural Society. The purpose was to offer settlement services to immigrants and refugees settling in Brantford and Brant County and to encourage multiculturalism. The name of the organisation was later changed to Immigrant Settlement and Counselling Service of Brant.

Heritage building awareness started to gain traction in the 1980s. The demolition of heritage homes along Brant Avenue at Church Street for the construction of nondescript strip plaza became the lightning rod for action. A 1981 City bylaw restricting properties along Brant Avenue to residential offices or personal service businesses was rejected by the Ontario Municipal Board as not in the public interest, a more comprehensive study of the street would be required. The planning department proposed a heritage district to Council in 1983 but Council maintained their policy of not designating any building without the owners’ consent.

In 1987, the owner of the Commercial Building at the corner of Dalhousie and George Streets wanted to demolish the 106-year old building. Pressure from the City’s Heritage Committee and discussions with the owner led to the preservation and designation of this building. Council, realising how quickly and easily a prominent heritage building could be demolished due to a lack of any heritage protection whatsoever, moved to designate the streetscape of Brant Avenue as a Heritage Conservation District in 1989. The district encompasses buildings along Brant Avenue from the Lorne Bridge to St. Paul Avenue. The district consisted of 132 properties which include residential, commercial and public use buildings. Most of the homes were constructed between 1870 and 1889 as Brantford was experiencing an industrial boom. The movers and shakers of Brantford lived here and on adjacent streets during this boom period. The buildings feature traditional architectural styles including Neo-Classical, Italianate, Gothic, and Queen Anne, creating an interesting streetscape.

When the Brant County War Memorial was unveiled in 1933, it did not include the statue of soldiers that the designer, Walter S. Allward envisioned for the memorial. In 1956, a gallery honouring the fallen from the Second World War and the Korean War was added to the memorial. In 1987, a veterans group set up a committee to fundraise $300,000 for the addition of statues to the war memorial to complete Allward’s vision and design. Rather than six statues, seven statues were commissioned to recognise the efforts of women in the war effort. Winnipeg’s Helen Granger Young was the artist commissioned to design and build the statues.

Declining church attendance caused City congregations to begin to consider amalgamating. The old churches were costly to operate and maintain and declining membership meant reduced weekly collections. Colborne Street United Church and Zion United Church were the first to consider amalgamation. Although this merge did not occur, the template was set. Marlborough Street United and Cainsville United became the first two churches to merge, creating Harmony United Church in 1994.

Colborne Street East

The south side of Colborne Street from Clara Avenue to the TH&B underpass at the city limits was full of houses and businesses, Clubine Lumber, Sunys gas bar, and some restaurants. On 22-May-1986 a landslide of unprecedented proportions occurred. Four houses had to be evacuated, twenty more were threatened by further slides, and the TH&B rail line running along the edge of the Grand River was obliterated. This portion of Colborne Street lies above an ox bow in the river. The flowing river slowly erodes the river bank as the water rubs up against the shore as it changes direction around the bend in the river. 125 feet of the embankment was washed away. The landslide closed the rail line between Hamilton and Brantford for good as the slope was considered too unstable to repair the line. This was the largest landslide to take place in Ontario.

The City needed to stabilise the embankment and work out a compensation agreement for the affected property owners. The stabilisation effort would take between seven to ten years to complete at a cost of almost $15 million. Property owners were advised that if they chose to remain on their properties, it would be at their own risk. A compensation agreement was worked out between the province, the City, and the Grand River Conservation Authority. Compensation was based on the pre-landslide value of the properties. The province would pay 55 percent of the property value, and the GRCA ten percent. The remaining 35 percent would be split between the City and property owner. The property owners did not feel the compensation package was adequate and were prepared to appeal to the Ontario Municipal Board as the decade closed. All the properties were finally vacated and demolished by 2015.

Industrial Situation

The good times of the 1970s were expected to continue into the 1980s. Growth was projected to average three percent throughout the decade. However, the slowdown of the economy came fast and furiously. In July-1980, the total number unemployed in the City reached 4,500, in May it had only been 1,000.

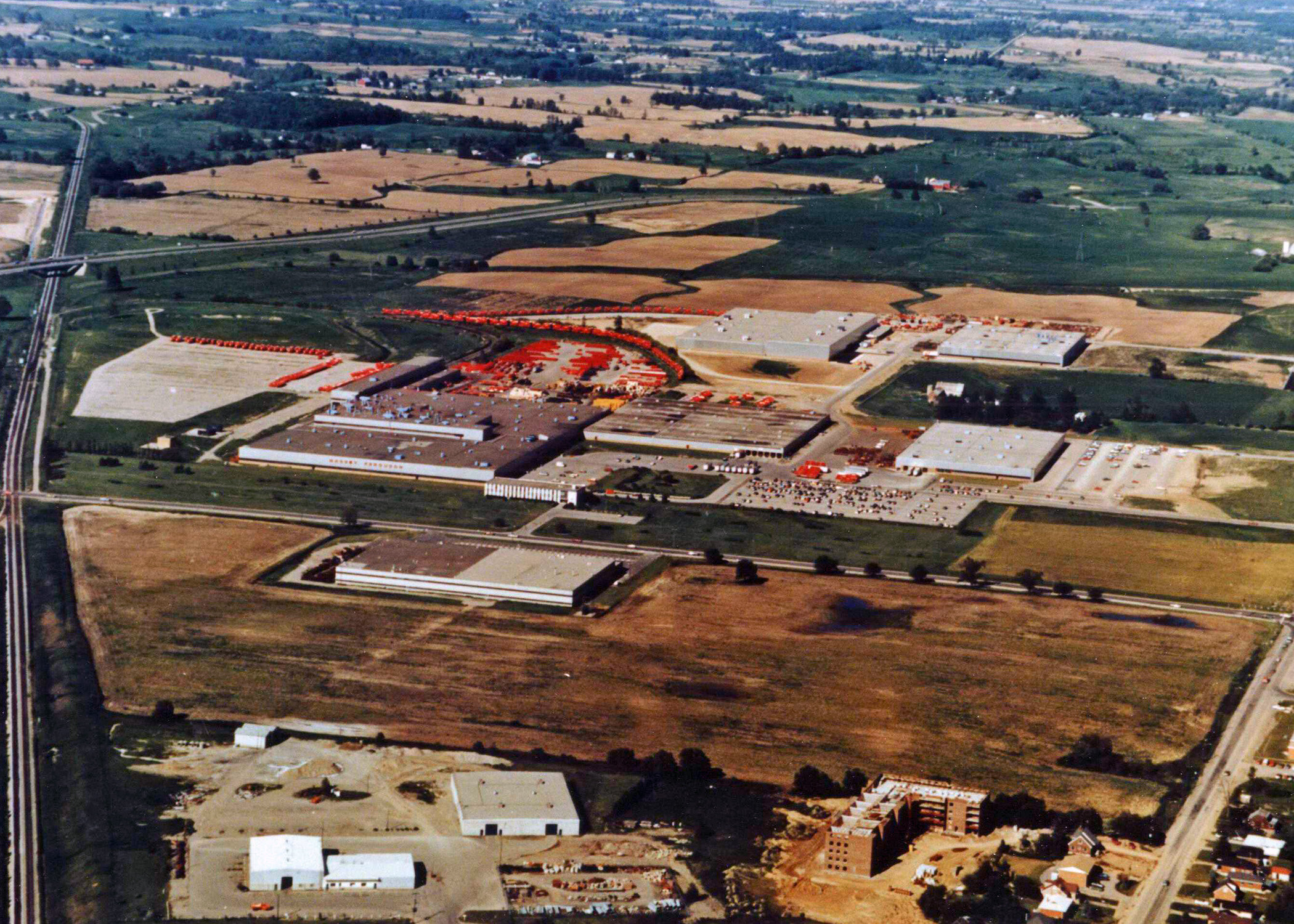

Massey-Ferguson and White Farm Equipment were in financial trouble, the worst they ever experienced. To conserve cash, Massey-Ferguson extended their usual one-month summer shutdown to three-months.

Aerial view of Massey-Ferguson’s Park Road North complex. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

The parent company of White Farm Equipment, White Motor Company of Canada, sustained heavy losses during the first six-months of 1980. This led to rumours that the Brantford operation would be sold or closed down. In July, White Motor Company of Canada entered into voluntary bankruptcy to reorganise their debt. The planned two-month shutdown of the Brantford White Farm Equipment plant was extended indefinitely.

Aerial view of White Farm Equipment’s Mohawk Street complex. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

By March-1981, the number of workers unemployed in the City had reached 6,200. The welfare rolls swelled to 1,200.

The workers at White Farm Equipment accepted a modified contract in March-1981. This lead to the recalling of workers laid-off and assisted in closing the sale of the company to Linamar Machine Ltd. of Guelph and Texas-based TIC Investment. In spite of these moves, 200 workers were laid-off in August as market conditions did not improve. These workers were not eligible for unemployment insurance because they did not work long enough to qualify.

In April Massey-Ferguson announced the closing of their factory in Des Moines, Iowa, moving 220 jobs to Brantford. The company also received loan guarantees from the federal and provincial governments. The Brantford plant was shut down in November because of the continuing poor market conditions; the second shutdown in two years.

Local service and support companies felt the effect of the shutdowns. Social services were dealing with a large increase in demand, demand that outstripped the ability to provide timely assistance. The Mayor-Warden’s Committee on Services to the Unemployed, a joint City/County taskforce, was organised so the newly unemployed would know what local community services were available to them. The Brant Social Services Committee was seeking federal and provincial assistance with welfare payments and job creation.

By the end of 1981, unemployment stood at over 22 percent, 8,000 workers were out of work. A Toronto writer wrote: …Brantford is taking a beating the likes of which hasn’t been seen since the Great Depression. Besides the high level of unemployment, the City faced a significant increase in welfare cases, an increase in property taxes, and a decrease in housing starts. Because of the publicity around how poor the local economy was, the City was not able to place $1.1 million worth of the bonds in the market at a reasonable interest rate in June-1982.

The City did not stand idle during these turbulent times. Efforts were made to diversify the local economy. Local manufacturers were asked to acquire their parts from local firms rather than importing them. Development of the Northwest Industrial Park began as the Braneida Industrial Park had virtually no vacant land available.

The federal government established the Industry and Labour Adjustment Programme, a scheme to provide funding for companies to relocate or expand in hard hit regions. The City’s request for ILAP assistance was approved in January-1982.

The expected turnaround at Massey-Ferguson in 1982 did not occur. Although 1,800 workers were recalled in January and the company announced that the production of four-wheel drive tractors was to start in November, continuing poor market conditions forced the shutdown of the plant in August. 200 salaried staff were also laid-off. In September, the company extended the shutdown into the next year and also shut down their Toronto plant.

The effects from the ILAP programme were felt immediately. After the one-year programme had run its course, Brantford had seen the best results of all the communities using ILAP, thus a six-month extension was granted. ILAP help create 3,000 new jobs in the area, twice the number originally expected.

At the end of 1982, 10,161 workers were out of work in a city of 75,000. The welfare rolls classified 60 percent of the recipients as employable.

White Farm Equipment was in poor shape although it did have one ace up its sleeve. The factory developed and held the patent for the manufacture of a new axial-flow rotary combine; a revolutionary development in combine engineering. In March-1982, the company announced plans to close the plant indefinitely, laying-off 925 workers. To keep the plant alive TIC Investment took control of the company and promised to guarantee 1,200 jobs until at least 1990 for the rights to the new combine. However, the company was not able to repay its bank loans and could not secure any further government assistance. On 13-June-1983, the banks forced the company into bankruptcy. The employees tried to buy the plant and the combine technology but were not able to raise the money. In December-1983, Borg-Warner Acceptance Corporation of Chicago bought the company and negotiated a new contract with the workers.

White Farm Equipment workers’ last pay day 13-June-1983 when the company first filed for bankruptcy protection. The company was placed into receivership one final time on 10-April-1985. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

With the new 9720 axial-flow combine the company was able to increase its Canadian market share from seven percent to twenty-two percent. In March-1985, 250 employees were laid-off. On 10-April-1985, the company was again placed into receivership. The province was willing to increase its loan guarantees, but the federal government was not. With no other money available, the company was forced to liquidate, after 108 years in business. The rumour was that Massey-Ferguson thwarted the rescue effort in order to get its hands on the axial-flow technology from the receiver. The contents of the company’s engineering centre went on the auction block in September-1985.

White Farm Equipment’s revolutionary 9720 Axial Flow (Rotary) Combine. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

White Farm Equipment’s auction of assets, September-1985. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Massey-Ferguson began calling back workers in January-1983. In April-1983, the company announced plans to close its Toronto plant within two to five years and move all production to Brantford. The plant’s future looked secure. In 1984 the company invested $5.5 million to upgrade its Park Road North complex. In 1985, the company announced it would be the major tenant at Massey House, a new office tower in downtown Brantford located across the street from the library. It is now Laurier’s Grand River Hall.

1985 turned out to be a disastrous year for the company, only 1,100 combines were produced. During the period 1979 to 1981 the company produced 35,000 combines in Brantford. 1,325 workers were laid-off in November-1985. When things look bleak and sales do not materialise what is a company to do? Reorganise. When everything else fails shuffle the deck.

At the end of 1985, the combine division was reorganised as a separate company; everything combine related was moved to Brantford including production, research, and marketing. In May-1986, Massey-Ferguson was divided into two separate companies, the combine company became Massey Combines Corporation, based in Brantford, and the rest of the company was reorganised as Varity Corporation. Varity was chosen to recognise the Verity Plow Company, an early constituent piece of Massey-Harris. Is it a coincidence that Varity rather than Verity was used? The president of the Massey-Ferguson at this time was Victor A. Rice - VARity. Varity moved to Buffalo, NY in 1991 and ceased to become a Canadian company.

Massey Combines Corporation baseball hat. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Virtually all of the debt of Massey-Ferguson was transferred to Massey Combines, creating an unsustainable financial situation for the new company. Unable to meet its payment to a creditor, the company was forced into bankruptcy on 4-March-1988. The unimaginable, Brantford without Massey, became reality. As much as the closing was expected, the finality still came as a shock to the city.

Was the separation of Massey Combine and Varity Corporation an attempt by Victor Rice, Massey-Ferguson’s President, who engineered the reorganisation, an attempt to jettison an unwanted and unprofitable portion of the business? The bankruptcy resulted in retirees with capped pensions and no health benefits.

As the drama of the decline of the two pillars of the Brantford economy played out, the City was busy improving and expanding its industrial base. The unemployment rate in the City dropped drastically by the end of 1983. The City’s Director of Economic Development declared 1984 as a banner year as 14 new companies established themselves in the City.

Success continued into 1985. 28 new manufacturing firms located in the City in two years which led to the creation of 1,600 new jobs. The City no longer had trouble selling its debentures. The unemployment rate had decreased to 12 percent by October-1985. Building permits had increased and Revenue Canada reported that workers in the City were making more money.

Some of the new names on the industrial scene included Westcan Electrical Manufacturing Ltd., attracted by the ILAP programme, Kuriyama Canada, the City’s first Japanese company, that specialises in hoses for agricultural and industrial machinery, Inmont Canada, a manufacturer of paint finishes for the auto industry, Slacan, a division of Slater Steel, and Koolatron Corporation, a manufacturer of portable refrigerators. Although Brantford was not able to attract the new Toyota plant or the GM/Suzuki joint venture, the closeness of the plants to Brantford helped automotive parts suppliers in town.

The City purchased 150 acres of Massey Combines property to add to its industrial land reserve. The Massey complex became the Brant Trade and Industrial Park that attracted small and large industrial tenants. In November-1989, Stelco Fasteners, a bolt and nut supply for the auto industry, became the Park’s first major tenant. 67 new companies settled in Brantford between 1988 and 1989.

Strikes

Workers at Worthington Canada went on strike for five months in 1980. This strike made history as the first test case of a new provincial labour law requiring employees to vote on a final offer if requested by the company.

Employees at Trailmobile were on strike for eight months in 1983. It was a nasty strike marked by acts of vandalism. The strike ended when the company threatened to close down the plant if a settlement could not be reached.

In 1979, employment at Hussman Refrigeration Company had reached 600 workers, but by 1983 it was down to 350 because of the economic downturn. During contract talks in 1984, the company asked for a two-dollar an hour wage reduction for new workers and the elimination of the cost of living bonus. These were hard won benefits that the union refused to surrender. The strikers remained on the picket line for eight months. After the company threatened to close the plant if no agreement was reached by 4-September-1984, the two sides settled with neither side gaining what they originally asked for.

Royal Visit to the Mohawk Chapel, 1-October-1984. The visit was to unveil a plaque recognising the first Protestant church built in Ontario (1785) as a National Historic Site (1981). The visit was short, 75 minutes. The Queen is picture with Premier William Davis (left), Chief Wellington Staats (centre right), and Prince Philip (right). (photos courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

In September-1984, 3,000 civic workers walked off the job. Job security was their number one issue. The Queen’s visit to dedicate the Mohawk Chapel was almost called off because strikers threatened to picket during her visit. During the strike, downtown garbage was not collected and access to civic construction sites were picketed, slowing down access to the sites. A Council meeting was interrupted by strikers and police were called. Police also had to accompany non-unionised salt truck drivers after a window in one of the truck was smashed while it was in use. A 29-hour bargaining session in December-1984 concluded with an agreement. The 15-week strike was over.

Bus drivers for the Public Utilities Commission walked off the job for seven-weeks in 1988; the first strike in the PUC’s history. The issue was the removal of a clause whereby drivers were picked up before their shift and returned home after their shift by a special bus. The drivers surrendered this clause and accepted 10 minutes extra paid time travel time.

Plant closures

Crown Electrical Manufacturing closed in 1982. The company had been in business for 72 years.

Spalding Brothers closed their factory on Spalding Drive in September-1982. The company had been in Brantford since 1913. 270 workers lost their jobs.

Spalding Plant. This plant opened in September-1955 and replaced their Edward Street facility which was originally the A.G. Reach Company of Canada, also a maker of sporting goods equipment. The two companies merged in 1926. Spalding made golf clubs, Topflite golf balls and golf bags in Brantford. This plant closed in September-1982, 17 years after it opened. Canarinda Manufacturing Ltd. of Waterford purchased the golf making equipment in 1983. The building is currently unoccupied. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

In March-1983 York Farms announced it was closing its plant on Canning Street and Colborne Street West resulting in 100 people out of work. This plant is now the Maple Leaf Foods chicken processing plant.

Etatech Industries was forced to close in 1987. The company was established in Brantford in 1919 as Robbins & Myers. The business had been employee run since 1978.

Etatech Factory at 58 Morrell Street was built in the early 1920s to make electric motors for the Canadian market. Initially the company built vacuum cleaner motors, eventually they made electric motors for almost every use. In 1978 this business was sold to a group of employee and renamed Etatech Industries. The company went into receivership in 1987. The building is currently unoccupied. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Transportation

Highway 403 remained the only unfinished 400 series highway in the province. This highway was conceived in the 1950s. The Brantford cutoff portion opened on 31-October-1966, yet the highway still did not connect to Highway 401 in the west or the Queen Elizabeth Way in the east. Motorist still needed to travel Highway 2 at either end to complete their trip. Highway 2 in the west was a two-lane highway carrying heavy truck traffic. Highway 2 between Brantford and Hamilton was a four-lane highway that carried trucks and heavy commuter traffic. This portion was especially hazardous because traffic travelled well above the posted 80 km/h speed limit yet there are numerous roads, farms, houses, and businesses that front on the highway with cars and trucks turning into and out of these places. The traffic was so heavy that at times a motorist could wait 20 minutes on White Swan Road to find an opportunity to turn left onto Highway 2. Between 1978 and 1986, 710 accidents were reported on this stretch of highway resulting in 23 deaths.

Highway 403 was a vital route to and through the City, much like the railways were 80 years before. It was completed to the junction of Highway 53 outside Woodstock in 1985. The interchange with Highway 401 in Woodstock was completed in 1988. Pressure was applied to the provincial government from local citizens and governments to complete the eastern portion of the highway. In 1987, the provincial government agreed to begin construction of this portion of the highway in 1989 with completion expected by 1996. The highway finally opened in August-1997.

Even though the Brantford Southern Access Road (BSAR) was identified as a key component in the City’s traffic system, the 1980s saw little progress on this road. In 1985, after twenty years of negotiations, the City reached an agreement with Six Nations for a right-of-way across the Glebe property, behind Pauline Johnson Collegiate. The City also worked with the province to build an overpass over the CNR mainline tracks on Park Road North to eliminate the second most dangerous railway crossing in the province. In 1988, the City completed an agreement with the province for financing the portion of the BSAR between Market Street and Colborne Street at Park Road North. In 1989 a new agreement with the province replaced the 1969 agreement whereby the province agreed to pay 75 percent of the cost of land, design, and construction of the roadway. The money would be allocated before 1994. The BSAR was expected to be completed coincident with the opening of the eastern portion of Highway 403.

The Victoria Bridge on Market Street South was closed in 1983 in preparation for the construction of a parking garage. The bridge opened in 1912. It was damaged by a box car hitting the underside of the bridge in 1977. The bridge was demolished in 1984.

Victoria Bridge. This series of photos shows the bridge from Colborne Street looking south, a profile of bridge looking east before the canal was covered over, and the demolition of the bridge to make way for the downtown parking garage. (photos courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

The Mulroney government’s 1989 budget slashed VIA Rail’s funding drastically; VIA’s operations were to be reduced by 55 percent. This resulted in the reduction of VIA service in Brantford to eight trains a day. Previously nineteen trains a day serviced the City. Rail users and cities along the VIA corridor protested the cuts to no avail. VIA did, however, add a morning commuter train that ran between London and Toronto stopping in Woodstock and Brantford. The train became an express train between Brantford and Toronto.

The main runway at the Brantford Airport was extended 1,000 feet, to a length of 5,000 feet, in preparation of Queen Elizabeth’s visit to the Mohawk Chapel in 1984. This was done to accommodate corporate jets.

Police and Fire

A 1979 report of the Ontario Police Commission was finally released in the early 1980s. The report supported a 1976 report that recommended a reduction in the force’s complement. The reports concluded that taxpayers were subsidising an inefficient police force. The Police Commission rejected the report’s conclusions.

In 1981, the Police introduced yellow cars as they were deemed more visible, similar to school buses. However, the specially mixed colour became harder and more expensive to acquire. In 1988, the yellow cars were replaced with white cars.

Yellow Police Cruiser. The Brantford Police used yellow coloured cruisers between 1981 and 1988. In 1988 the yellow cruisers were replaced with white cruisers. (photo from Pinterest by Timothy Boniface)

Mary Jane Hammond vanished during the early morning hours of 3-September-1983, walking to her job at a bakery on Morton Avenue East. An extensive police investigation that included the use of hypnotism on two witnesses turned up no useful clues. The mystery of Mary Jane’s disappearance has still not been solved.

In October-1983, the Crime Stoppers programme was introduced. This programme is designed to assist police with information by obtaining tips from the public.

The City’s police station was in dire need of an upgrade and expansion by the 1980s. The police station, opened in 1954, was designed to accommodate 90 people. In 1985 the police department had 138 people working at the station. A 1986 report noted that a station would need almost twice as much space as currently existed and contain facilities for female officers. Money for a new station was cut from the 1986 budget. A 1988 public inspection again raised the issue. The options were expansion or a new build. The Police Commission favoured a new build at Park Road North and Elgin Street. Council rejected this proposal and asked the Commission to review all possible locations. Thirty locations were reviewed and the Park Road North at Elgin Street location was again recommended. Council approved this recommendation in February-1989, but the delay saw the cost of the project increase by $2 million.

In May-1985, the department’s first two female constables were hired, Judy Hobbs and Nancy Nichol Bielawski. The women faced a number of challenges. Their uniforms were tailored for men and the Station on Greenwich Street lacked a change room for female officers; the constables used a storage closet to change.

In 1986, the police acquired a mobile command centre at a cost of $79,000. It looked like a recreational vehicle crammed full of communication equipment.

In 1989, the downtown foot patrol was reintroduced in order to increase police presence downtown. A police substation was also opened.

As the economy deteriorated, crime increased, including violent and drug-related offences. The crime rate in 1983 was the highest in the province. By 1989, the rates of crime had declined.

Fires continued to plague the City. In 1982, a fire of suspicious origins destroyed the Iron Horse Restaurant on Market Street South at Erie Avenue. The restaurant was housed in the former Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo railway station. The building was rebuilt restoring the train station.

A house fire in 1985 claimed the lives of three children. The coroner blamed City Council for not enacting a smoke detector bylaw. A coroner’s jury had recommended in 1982 that the City pass a smoke detector bylaw but no action was taken. A month after the 1985 fire City Council passed a smoke detector bylaw requiring smoke detectors in all homes and rental units. Landlords were required to install and maintain smoke detectors in their buildings.

In December-1986, two warehouses of the former Cockshutt Plow Works caught fire. The blaze was fought by 23 firefighters.

Health Care

In 1979, the provincial government introduced the concept of rationalisation in health care. The idea was to be more efficient with health spending by making hospitals work together to specialise in the services they offered; to eliminate duplication. In 1980, the Brant District Health Council accepted a plan where the Brantford General Hospital would have the only emergency department. St. Joseph’s would continue as an active treatment hospital, open a day hospital and increase their number of chronic care beds. The Brantford General Hospital would lose over half of their chronic care beds. The Willet Hospital in Paris would become solely a chronic care hospital. The Brantwood Residential Development Centre would become a centre for children with multiple challenges, losing their chronic care beds.

The Willet Hospital (1971) in Paris when it was still a stand alone hospital, before it became part of the Brant Community Healthcare System, and before the building was expanded with an addition built in front of the building. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

A shortage of chronic care beds plagued the health care system in Brantford for years. This shortage meant that elective surgeries were routinely cancelled. Patients needing chronic care beds were housed in storage rooms, lounge areas, makeshift wards, and stretchers throughout the hospital. Chronic care patients were being placed in short-term stay beds. In 1987, the Brantford General Hospital had 94 chronic care patients but only had 23 long-term care beds.

The John Noble Home, a long-term care facility where 350 people resided, was in poor condition. The roof leaked, and the boiler was irreparable. $9 million would be needed to bring the facility up to first class standards. This situation exacerbated the chronic care bed shortage because this residence was supposed to alleviate the need for long-term beds at the hospitals. The City considered selling the home to the private sector but relented and decided to upgrade the facility. Upgrades occurred slowly. By 1989, the cost had escalated to $12.4 million.

Health care programming, however, was advancing. A birth control centre opened in 1982. A new emergency and radiology department opened at the Brantford General Hospital in 1984. A CT scanner became operational in 1989.

Education

In 1979, it was proposed that the public-school board, separate school board, and the City’s Parks Board work together to build a combined school and recreation complex in the Brantwood Park neighbourhood. Negotiations to proceed moved slowly. In 1987, ground was broken on the complex. This initiative was the first of its kind for Ontario. Never before had two school boards and a city worked together to jointly develop a facility. Branlyn Community School, Notre Dame Separate School, and a community centre opened in the fall of 1988. David Peterson, the Premier of Ontario, attended the opening.

In August-1980, King Edward School was closed. Built in 1890, the school was originally known as Huron Street School. It was renamed King Edward School in 1907 in honour of King Edward VII. The vacant school, located at 55 Edward Street, burned down on 13-June-1981.

After a fierce battle between parents and the public-school board that lasted ten years, the Cainsville School was closed on 30-June-1988. The school was originally build in 1920. An addition was completed in 1951. The school population was amalgamated with Woodman Drive School, and the school was renamed Woodman-Cainsville School.

Central School, the City’s oldest school, was in poor condition. The school opened in 1891. The school board wanted to demolish the school and build a new one. Heritage advocates wanted the school designated and renovated. A fire on 10-March-1982 that seriously damaged the school looked like it would end the matter, but the heritage advocates continued their fight for designation and obtained an injunction against the demolition. The City turned down the request to designate the school and the school was razed. The new and smaller Central School opened in October-1983. During excavations for the new school, 28 graves were unearthed. The school’s site was designated as a burial ground in the original 1830 survey of Brantford.

Full public funding for Separate schools (Catholic schools) was implemented by the provincial government in 1984. This decision caused a spike in enrolment to the Separate school board’s high school; a migration of students from the public high schools to the Separate high school. St. John’s College had a student population of 1,300 pupils in 1987, in a school designed to house 750 students. Portables thus became the norm. Initially provincial funding to enlarge the school was denied because there was surplus space in the public schools however, in 1988, $4.7 million was made available to finance the expansion of the school. The Separate school board also began to lobby for a second high school in the City.

A Breakfast Club was launched at Victoria School to ensure all students began the day with a full stomach. A half-day nursery school opened at Pauline Johnson Collegiate to accommodate single mothers and adult students. An alternative school was established at Victoria School in 1985 for students that had problems learning in a traditional school setting. The programme expanded to Fairview School in 1988. Special adult classes started at North Park Collegiate for adults wanting to return to high school. The public school board began to offer classes for 18 to 20 year olds incarcerated at the Brantford jail. Some students from the Jane Laycock School were moved to Prince Charles School to place them in an inclusive setting.

Mohawk College expanded their programming in 1983 from two to seven courses. The College created a downtown campus for adult retraining when the Richard Beckett Building opened in 1985. To this point the College functioned as an adult retraining centre. In 1987, it was proposed that the Brantford campus be expanded to accommodate 1,100 students and that programmes tied to the proposed telecommunications museum and an adult education centre for the visually impaired be established. The price tag was $38.7 million. The provincial government rejected the plan but did offer funds to enlarge the campus.

Enrolment in the French immersion programme offered by the public board had risen to 508 students by 1989. To contain the cost of running the programme the public school board suggested that enrolment not begin until grade four. The community voiced their outrage and the idea was dropped.

Recreation

In 1981, City Council created a committee to study the recreational potential of the 22 miles of the Grand River passing through the City with particular attention on the area between the Lorne Bridge and the Brantford Southern Access Road bridge, including Earl Haig pool. Using the committee’s September-1982 report, contributions from the community, and funding from the Canada-Ontario Employment Development programme, work began on cleaning up and improving the river front, and developing and extending walkways and bicycle paths.

Earl Haig pool closed in 1983. It was in dire need of repairs. The plan was to rebuild the pool. The facility was demolished, and excavation work was completed. While waiting for the concrete to be poured for a new pool, the City learned that the cost for the pool had risen by $150,000. The City abandoned the project and in 1987 filled in the hole. This left the Eagle Place neighbourhood without a pool. The idea was then floated of building a leisure pool.

The City continued to improve Mohawk Park. The improvements resulted in an increase in the number of people who used the park. To stimulate even greater usage of the park, a project was launched in 1987 to study the feasibility of cleaning and restoring Mohawk Lake for recreational purposes. In the meantime, the Waterfront Advisory Committee worked to raise funds for boating facilities and to build an observation deck as a start to adding attractions that once made the park a popular destination. The Brant County Medical Officer of Health put a damper on this initiative when he warned that no lake activity should resume until the lake was cleaned.

Joseph Brant monument in Victoria Park. The monument was designed by sculptor Percy Wood of London, England. The statue of Joseph Brant stands nine feet high. The monument was unveiled on 13-October-1886, and fully restored in 1984. (photo by the author)

The Brantford Highland Games came to an end. Operating since 1964, the organisation disbanded because of a lack of community support. The International Villages Festival continued and celebrated its tenth year in 1984. Riverfest was launched in 1988 to celebrate the City’s Grand River heritage.

The Joseph Brant statue in Victoria Park was restored in 1984. Over the years, the mortar crumbled from the joints and pieces of the bronze statuary went missing. All monuments in Brantford are now regularly maintained on a rotating schedule.

On 1-October-1984, the newly renovated Mohawk Chapel, more formally known as Her Majesty’s Royal Chapel of the Mohawks, was dedicated as a National Historic Site by Queen Elizabeth accompanied by Prince Phillip. The Royal couple planted a white pine tree and unveiled a plaque inscribed in English, French, and Mohawk.

Lorne Park floral display commemorating the two-hundredth anniversary of Her Majesty’s Royal Chapel of the Mohawks, more commonly known as the Mohawk Chapel. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Housing

All types of housing were in demand in the 1980s, but there was a shortage in some categories. The Ava Golf course was turned into a subdivision of executive style homes. The old St. John’s College campus on Dufferin Avenue was converted into row type condominium housing. Plans to renovate the Penman’s factory on Grand River Avenue to, first a hotel, and then apartment style condominiums were not successful. The building later burned down. Plans to develop the Massey complex on Greenwich Street into a mixed development including housing, commercial and light industries also did not materialise.

Low rental and geared-to-income housing continued to be in short supply. To address this need, the City created a not-for-profit corporation to develop and operate housing projects. The situation grew so dire that some people were forced to live in parks and motels. Some families had to put their children into foster homes because they were unable to find suitable accommodations. Bylaws were also created to regulate the size and location of group homes to ensure they were not concentrated into a few neighbourhoods.

Sporting Matters

The Brantford Bisons junior football team disbanded in 1982. Declining fan support and player interest led to the team’s demise. The Bison Alumni however still remain a force in the City, supporting minor sports of all kinds and at all age levels.

Brantford Alexanders pennant - The Brantford Alexanders played at the Brantford & District Civic Centre in the Ontario Hockey League from 1978 to 1984. The team was named after Alexander Graham Bell. It missed the playoffs only once while in Brantford, during its first season. (image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

In 1984, the Brantford Alexanders Major Junior A hockey team left the City for Hamilton. Fan interest waned even though the on-ice product was competitive. The team had reported losses of $100,000 per season for several years. During the 1984 and 1985 hockey season, the Flamboro Mott’s Clamatos Senior A team played part of their season at the Civic Centre. In 1986, the team moved its entire operation to Brantford. Known as the Brantford Mott’s Clamatos, the team won the Allan Cup that season, Brantford’s second Allan Cup in ten years.

Gary Summerhayes retired from boxing in 1980 after losing the Canadian light-heavyweight title he had held for seven years. In 1982, Gary’s brother John, regained the Canadian light-heavyweight title in a 12 round split decision. John lost his defence of the title the following year at a bout at the Civic Centre.

Kevin Sullivan first gained international attention for his middle-distance running. In 1988, at age 14, Sullivan ran the 800 metres faster than any 14-year-old had even run that distance in competition. He continued to break records in 800 metre and 1,500 metre races.

The City renamed the North Park Sports Complex to the Wayne Gretzky Sports Centre in July-1982 in recognition of Gretzky’s accomplishments in the NHL. The City’s first choice was to rename the Civic Centre after Gretzky, but the Brantford and District Labour Council objected as they had been largely responsible for the building of the Civic Centre. In 1984, a Toronto art gallery proposed to place a 14-foot statue of Gretzky at the complex but the family objected to the gallery’s fund raising methods and blocked the project.

In 1981, Gretzky established an annual invitational tennis tournament in the city. The event evolved after a few years to a slow-pitch baseball tournament. The tournaments featured sports and entertainment celebrities. All profits from the tournaments went to the Canadian National Institute for the Blind.

The Brantford and Area Sports Hall of Recognition opened in 1985 to recognise nationally and internationally successful athletes from the area. The Hall opened honouring the achievements of 41 athletes.

On Christmas Day in 1987, the Petro-Canada Olympic Torch Relay passed through Brantford on its way to Calgary for the 1988 Winter Olympics.

Ben Johnson, the disgraced sprinter of the 1988 Summer Olympics was appointed parade marshal of the City’s 1989 Canada Day parade. Johnson was warmly received by the crowd. Johnson’s invitation to attend the 1989 Wayne Gretzky slow-pitch tournament was withdrawn because sponsors threatened to pull out of the event if he participated.

CKPC and the Canadian Caper

CKPC button (image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

After the U.S.-backed Shah of Iran’s regime fell during the Islamic Iranian Revolution, Islamist students and militants seized the U.S. embassy and all embassy personnel in Tehran on 4-November-1979. Six Americans managed to escape and after six days were given sanctuary at the residences of Canadian Ambassador Ken Taylor and his wife Patricia and Immigration Officer John Sheardown and his wife Zena. A plan was hatched by Taylor with the support of Prime Minister Joe Clark and Secretary of State for External Affairs Flora MacDonald to smuggled the Americans out of Iran with the assistance of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. An Order in Council was made to issue the Americans Canadian passports with fake identities. As time passed Taylor feared the Americans’ concealment may have been discovered by the Iranians so plans were accelerated to get the Americans out of Iran. By this time Taylor had reduced embassy personnel to a skeleton crew. The Americans left Iran with Canadian passports on Sunday 27-January-1980. The story was broken by La Presse reporter Jean Pelliter on Monday 28-January in Montréal. The Canadian embassy was quietly closed on Monday and Taylor and the remaining staff returned to Canada.

During an election tour through southern Ontario on Tuesday 29-January-1980 Joe Clark was in Brantford, appearing on the CKPC programme “Off the Cuff”, hosted by John Best. It was at CKPC, in front of television cameras, with the CKPC logo featured prominently behind Clark, that Clark revealed Canada’s role in helping the American hostages escape Iran. 52 Americans remained in captivity until 20-January-1981, after 444 days, when they were released, the day Ronald Reagan assumed the presidency from Jimmy Carter. Joe Clark went on to lose the 1980 federal election on 18-February-1980, that saw Pierre Trudeau returned to office.

Commercial Developments

C. Mady Leaseholds of Windsor began development of a plaza on King George and Kent Roads in August-1984. The 60,000 square foot plaza sported a 40,000 square foot A & P supermarket. The A & P opened in May-1985. A & P closed their two 1950s era supermarkets in Brantford in 1976. One was located at Dalhousie and Stanley Streets, now a McDonalds, and the other at King George Road and Queensway Drive. The A & P is now a Food Basics, a banner owned by Metro. Metro acquired A & P in 2005 and rebranded the stores to Metro in 2009. Food Basics has operated since 1999. A & P opened its first stores in Canada in 1927.

On 4-August-1986 a major expansion to Lynden Park Mall opened. The expansion increased the number of stores at the mall from 55 to 100. The expansion opened almost 12 years to the day the mall first opened on 1-August-1974. The expansion created a circular traffic pattern to the mall and added a food court. At the time of expansion Kmart, Sears, and Miracle Food Mart were the major anchor tenants of the mall. The addition included Marks & Spencer, A & W, Manchu Wok, MMMarvellous MMMuffins, Atlantic Video and Sound, Living Lighting, Micro Cook Centre, St. Clair Paint and Wallpaper, J.H. Young and Sons, Bijou, Boutique Marie Claire, L.A. Express, Foot Locker, Tip Top Tailors, Mister Minit, Aggies, Ashton Shoes, The Coffee Bean, The It Store, Sunrise Records and Tapes, Le Chateau, Pantorama, and Thrifty’s, among many others. There are a lot of memories shopping at these various stores, most no longer around. The mall had plans to expand their retail space and add office space when the demand arose. These additions were never built.