Brantford in the 1950s - Post 19

During the 19th century, Brantford led Ontario in expanding municipal services for its residents and had a well-developed infrastructure of city services. It was able to do this because the early civic leaders understood they were in competition with newly developing cities and towns to attract capital and settlers.They reckoned that a progressive and modern town would be an attractive place to settle and invest. However, by the end of the First World War, Brantford needed to be rebuilt and modernised. In addition, demand for new services continued. Providing funding for these services while keeping taxes low required compromise

By the mid-20th century, Brantford’s standing as a leading and progressive municipality in Ontario and Canada began to diminish. The depression and war years had taken their toll on City services as the funding levels had not kept pace with demand and routine maintenance. The continued postponement of needed expenditures by municipal governments during these periods only delayed the inevitable. The baby boom that started after the war further compounded the situation as demand for school space and City services soared. A perfect storm hit Brantford.

The Brantford we are familiar with today began to take shape during the 1950s.

City Council

As the 1950s began, Brantford was faced with a substantial services deficit. Boundary expansion, traffic congestion, lack of downtown parking, industrial expansion, hospital overcrowding, expanded and new schools, arena and performing space, and sewage treatment all competed for Council’s attention and funding.

Years of inadequate funding meant property tax increases were necessary, but tax increases are unpopular and Aldermen, now called Councillors, were elected to one year terms, so their performance was constantly under scrutiny. Two year terms were adopted in 1957. Short election terms equate to a focus on short term achievable goals. Noble, long term intentions do not always translate into popularity. Longer term goals can be ignored when a pressing current issue has the attention of voters.

Brantford had become a victim rather than a beneficiary of its conservative fiscal policy. Brantford would finally abandon its pay-as-you-go philosophy in 1957 because the need for capital expenditures could no longer be met unless financing could be spread over the life of the project through the issuing of municipal debentures.

Tension among councillors increased during the fifties. Disagreements over civic spending, the appointment of a new city clerk in 1956, the consideration to add a City Manager, the entitlement of Aldermen regarding City assets, allegations of bribery, and a parking meter scandal created a circus like atmosphere at council meetings.

Boundary Adjustment

Brantford’s ability to increase its tax base was being hampered by a lack of land to develop. This lack of serviced land caused industries to pass Brantford by. In 1952, Canadian General Electric built its $8 million heavy equipment plant in Guelph Township because space was not available in Brantford.

There were two possible solutions, annex land from Brantford Township or amalgamate with Brantford Township. The City and the Province favoured annexation of Township lands. Despite the missed opportunities for Brantford to attract large industrial developments, negotiations between the two councils was pursued lackadaisically. When talks finally began in earnest in 1952 the two sides were far apart. The City was seeking 3,400 acres and the Township was offering 500 acres. Faced with an impasse, Brantford appealed to the Ontario Municipal Board (O.M.B.). Brantford withdrew their appeal in January 1953 to allow for further discussions but these talks also failed so the City reapplied to the O.M.B. but this time asked for 7,900 acres of land which included the suburban Township subdivisions adjacent to the City. The Township argued it would dissolve as a community since its tax based would be decimated. The City countered that it was stagnating. In October 1954, the O.M.B. ruled in the City’s favour. The annexation would be effective on 1-January-1955. With this annexation, the City’s population increased from 37,000 to 50,000. The total area of the City increased by 350 percent, from 3,178 acres before annexation to 11,078 acres after. Little opposition was received from Township residents affected by the annexation. However, anxiety surfaced in 1956 when former Township residents received their tax assessment and were upset by the property tax increases.

City Council commissioned a Master Plan to guide the development of the new enlarged City. This plan was needed to assist Council in the prioritising and costing of municipal improvements. Had plans been developed in the past, the City would likely have avoided some of the problems that came home to roost after the war.

Annexation of Brantford Township lands to 1960. Image courtesy of the City of Brantford Planning Department

Market Square

In 1950, the sad condition of City Hall and the relocation of the Farmers’ Market headed Council’s list for downtown improvements. It is interesting to note that as early as 1895, City Hall was regarded as an eyesore and an embarrassment to the City, yet fifty-five years later it was still the seat of municipal government. Given its location in the bustling retail and commercial centre, City Hall sat on prime land that was not producing revenue for the City. In 1951, Council decided to move the Farmers’ Market to the canal basin on what was then Greenwich Street, now Icomm Drive, its present location. By the end of the fifties, the Market remained on Market Square. In April 1951, a Toronto development company proposed to purchase and develop the Market Square but nothing further became of the proposal. In 1958, an American investment syndicate made a verbal offer of $1 million for the Market Square to build a five-storey building and 400 car underground garage. Again, nothing became of this proposal but the proposal did note that the downtown was vulnerable to suburban developments and the downtown needed a catalyst to remain relevant and vibrant. The City did take one step in 1957 regarding City Hall when it purchased the Y.W.C.A. building and property at the corner of Wellington and George Streets for $67,000. As the 1950s ended no decision was reached on what to do with Market Square. Debate ensued around keeping City Hall on site, selling the property outright, or converting the property to a parking lot.

YWCA on Wellington Street at George Street. Site of the Brantford City Hall. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Downtown

Traffic downtown was a mess; rush hours were accompanied by gridlock. This situation was the result of no alternative routes for through traffic to avoid downtown. In June 1951, the Brantford and Suburban Planning Board’s traffic study made the following recommendations: convert Colborne and Dalhousie Streets to one-way streets, implement parking restrictions, convert the Market Square into a parking lot, locate the bus terminal just outside of the downtown area, purchase land for off-street parking, and synchronise the traffic lights on the newly configured one-way streets. The downtown merchants were not in favour of one-way streets, but despite their protests City Council decided to implement one-way streets on a 4-month trial basis. On 4-August-1954, Colborne Street, Dalhousie Street, King Street and Queen Street became one-way streets. The public supported the changes and on 6-November, the change was made permanent. Strangely, City Council twice declined to act on synchronising the traffic lights on these one-way streets, in 1954 and 1958. In 1957, eight more streets were converted to one-way.

The Brantford and Suburban Planning Board’s traffic study also indicated a need for 500 off-street parking spaces. 200 spaces were opened on the canal basin along Greenwich Street in November 1950 and all-day parking meters were installed on Market Square in January 1951. The planning board report also noted that it would be in the interest of the downtown merchants to build their own parking lots or have the City provide parking lots for a fee and to refrain from using street parking for their staff and themselves. Failure to increase the number of parking spots available downtown would render the downtown vulnerable to suburban plazas that provided free parking. The Board’s warnings were not heeded and the downtown parking problem continued.

1952 aerial photo of downtown Brantford and Market Street South industrial basin. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

a) Armoury, b) Prince Edward Hotel, later the Best View Hotel, c) William Patterson & Son Co. Ltd., Confectionery & Biscuit Manufacturers, d) Federal Building, e) City Hall, f) Hotel Kerby, g) Brantford, Norfolk & Port Burwell (CNR) freight shed, h) Lake of the Woods Flour Mill. The mill closed in 1956 and was demolished in the early 1960s, i) Victoria Bridge (Market Street South), j) Interchange yards between the Lake Erie &Northern Railway (LE&N) and the CNR, built over the canal, k) LE&N Railway station, l) LE&N line to Port Dover, m) Greenwich Street, n) Scarfe & Company, paint and varnishes, o) CNR rail line to Tillsonburg, originally the Brantford, Norfolk & Port Burwell Railway, p) Massey-Harris Company, South Market Street plant, q) Waterous Limited, later Koehring-Waterous, then finally Timberjack, r) Freight yards of the Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo Railway (TH&B).

Transit

The rapid rise in automobile ownership was taking a toll on the City’s transit revenue. 1949 was its last profitable year. In 1952 the transit service posted its first deficit which quickly multiplied in the coming years. To compound matters, the 1955 annexation increased the services’ geography significantly. The City wanted the service to run on a self-sustaining basis but deficits continued to escalate. Service cuts were implemented and in 1956 Sunday service was discontinued. Reducing service rarely results in increased ridership.

Housing

The emergency housing complex established at the former pilot’s training school at the Airport was becoming a distraction for the City. The community was not located in the City and received no City services. The community was established to alleviate the post war housing crisis. As the housing situation began to improve in the 1950s, the City was intent on closing the community rather than investing in maintenance. In June-1953, the remaining residents were asked to vacate the community as the buildings were rapidly deteriorating. In 1959, a survey identified a need for geared to income housing and plans were made to build 50 rowhouses in Eagle Place with the assistance of the provincial government.

Bell Homestead

Brantford and Boston have long had a friendly competition regarding the claim as to where the telephone was invented so it came as a pleasant surprise when, on 7-May-1950, the Boston Sunday Herald wrote the following: It was during a vacation at Brantford in July 1874 that Bell first conceived the principle that underlies not only telephony, but television, radio and sound motion pictures as well… This recognition of principle always constituted for Bell the actual invention of the telephone. On 12-September-1953, the Historic Site and Monument Board of Canada unveiled a cairn to commemorate the invention of the telephone in front of the Bell Homestead. The Homestead would finally receive its designation as a National Historic Site of Canada on 1-July-1996.

Black Sunday 24-September-1950s

The afternoon of Sunday 24-September-1950 will always be remembered by those who lived through it. Shortly after 1PM the skies over Brantford began to darken. Street lights came on and cars needed their headlights. Darkness descended over Brantford and the northeastern United States. By 4 PM the sky began to brighten and the roosters began to crow. Speculation as to the cause of the phenomenom included an eclipse, an atomic explosion, a tornado, a snowstorm, a flying saucer, and the U.S. Army trying to see if it could block out the sky. The odd darkening was attributed to high altitude smoke from forest fires in Northern Alberta and British Columbia. At that time forest fires were allowed to burn freely if they burned more than 10 miles from roads, rail lines, and communities. This darkening of the sky phenomenon has been reported throughout history, since biblical times, notably in 1547, 1706, and on 19-May-1780, 18-April-1860, and 19-March-1886. In 1915, Scientific American magazine cited a U.S. Forest Service Bulletin which listed 18 dark days between 1706 and 1910.

Edward Barbarian, Brantford’s Bad Boy

On 13-June-1951, Edward Barbarian was found, shot to death, in a ditch near Mount Pleasant. He was 28. He was a short, husky man, always impeccably dressed. He was tough and he was mean; people were afraid of him. He carried around a .38-calibre revolver. His police record began in 1939, when he was 16. He was convicted of robbery, theft, burglary, bootlegging, and receiving stolen goods. He spent two years in jail and 4 years at the Kingston Penitentiary. Barbarian’s name was synonymous with gambling, bootlegging, and racketeering. He was also a lady’s man; good-looking, alluring, and dangerous. He cruised around town driving a 1946 Cadillac. Barbarian’s fronts were a cigar store on Queen Street and the Golden Rail Restaurant at 63 Dalhousie Street. He was known to erupt in fits of rage from time-to-time and once threatened to kill every cop in town. His murder remains unsolved. Barbarian’s demise may be attributed to ahmot, the Armenian word meaning to never bring shame to the family.

War Memorial

In 1955, Mayor Reg Cooper made the completion of the war memorial a priority. The memorial was to be commemorated on 11-November but a delay in the supply of the stones pushed back the unveiling to July-1956. The Remembrance Gallery honours the sacrifice of 339 Brant County men and women who died in the Second World War and the Korean War.

Police and Fire

Two relics from the 19th century remained in use well beyond their designed lifespan, the fire station on Dalhousie Street and the Police Station, behind it, on Queen Street. These buildings were designed to serve the needs of 1900 Brantford, not a modern and expanding City. In 1952, the City decided to replace these antiquated facilities with new buildings at Greenwich and Newport Streets, built on reclaimed canal basin land (a former carp pond). The new stations opened in 1954 and were immediately beset with problems due to the land they were built on. As the buildings settled, walls cracked, pipes broke, and telephone and electrical problems occurred. The floors in the fire station sank two and one-half inches in 3 years. In 1955, the Canadian Underwriters’ Association recommended three more fire stations be constructed, more firefighters hired, and firefighting equipment updated. In 1959, a tender was issued for a second fire station to be constructed at St. Paul Avenue and Dundas Street.

Fires continued to rage throughout the 1950s. Wood framed buildings with wood flooring, dried out after decades of use where prime to ignite at the slightest provocation of carelessness. Many of these fires often stretched the resources, men and equipment of the fire department to their limit. Major fires included the blaze at Gazer Mill Stock Co. on Grey Street, near Park Ave, in May-1951, the Loblaws store at 197 Colborne Street in January-1956 (the store was located in the building adjacent to the east side of the present Library building), the Agnew-Surpass store at 166 Colborne Street, just west of Market Street, in November-1958, and the Stedman’s Bookstore fire in January-1955 which required every fire fighter and every piece of equipment in the City to fight. To complicate the situation, a break in the water main downtown forced the fire fighters to pump water from the covered canal on Water Street. Within 24 hours after the Stedman blaze had been put out, store manager Bill White started to reorder merchandise to restock the store at a temporary location from memory, aisle by aisle, shelf by shelf.

Aerial photo of Greenwich St, 1955. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

a) Brantford Hydro substation, b) CNR connecting track to the Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo Railway (TH&B), c) CNR rail line to Tillsonburg, d) Fire Station, e) Newport Street, f) Police Station, g) Masonic Temple. Brantford Mosque since 2005, h) Former Brantford Hamilton Electric Radial Railway line, i) Clarence Street.

Bridges

The need to replace the Ava Road bridge that crossed over the CNR tracks and connected Brant Ave with Paris Road was identified as early as 1924. Although the bridge was an important thoroughfare into Brantford, the bridge was in Brantford Township. Canadian National Railways was also difficult to negotiate with. Discussions regarding the replacement of the bridge were renewed in 1951 and an agreement was reached in 1954. The 1955 annexation put the bridge within the City limits. In 1957, it was decided to build the bridge at a 45-degree angle rather than at right angles as per the original bridge. Land was purchased from the Ontario School for the Blind to accommodate this change and in August 1959 traffic began travelling over the new bridge.

Ava Road Bridge. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

The dashed line identifies the proposed route of the new bridge to cross the Canadian National Railway’s mainline tracks connecting Brant Ave with Paris Road. The new bridge opened in 1959.

In 1957, the Brantford and Suburban Planning Board had determined that the Lorne Bridge was no longer adequate to carry the increasing amount of traffic using the bridge and that within five years the traffic congestion would be unbearable. The Board recommended a new bridge be located upstream of the Lorne Bridge, however, a 1958 consultant’s report recommended that a new bridge be constructed one-half mile downstream of the Lorne Bridge. This bridge was eventually built as part the Brantford Southern Access Route, now known as the Veterans’ Memorial Parkway. The bridge opened to traffic in 1972.

Highways and Railways

Around the turn of the 20th-century, the Grand Trunk Railway acquired land north of the City to construct a bypass to divert their freight trains around the City rather than travelling through the City. When the Grand Trunk commenced work to excavate and grade the right-of-way the railway discovered a high water table which rendered the land useless as a rail right-of-way. The ground turned to quicksand as it was excavated. In 1947, at the behest of William Henry Summerhayes, the chair of the Brantford and Suburban Planning Board, discussions between Brantford Township and the Canadian National Railway, the successor to the Grand Trunk, began to acquire the railway’s right-of-way. Negotiations concluded in 1954 for Brantford Township to acquire the abandoned right-of-way. The right-of-way ended up in the City after the 1955 annexation of Township lands. The intention was to build a highway to carry through traffic away from the centre of Brantford and to open up the north end to residential and industrial development. In 1959, the Department of Highways agreed to build a limited-access expressway along this route; the projected cost was $4 million. In 1958, the City began to plan for the Brantford Expressway, later to be known as the Brantford Southern Access Route.

In November 1949, the Echo Place Association asked City Council to build a road along the Brantford Hamilton Electric Radial Railway right-of-way to provide another route into town. This request would result in the construction of Glenwood Drive.

Highways 2 and 53 between Brantford and Hamilton was a very busy two-lane concrete highway. The concrete surface was laid in 1929. In the summer of 1950, the highway was widened to four lanes from the junction of Highway 54 to the county line. A second bridge over Fairchild Creek for east-bound traffic was added at this time. A few years later the four-lane highway was extended to Binkley’s Corners, at the junction of Highways 2 and 8 near Hamilton.

Passenger train service between Brantford and Tillsonburg on CNR’s Burford subdivision, formerly the Brantford, Norfolk & Port Burwell Railway ended on Saturday 24-April-1954 when mixed train M328/M329 made their final runs. Rail service on this line commenced on 1-January-1878. On Saturday 25-September-1954, the last Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo passenger train left Brantford for Hamilton, ending 59 years of passenger service on the line. The freight office moved to the closed passenger station until the station building was sold in 1969.

On Saturday 23-April-1955, the Lake Erie & Northern Railway made its final passenger service run between Galt and Port Dover. On 25-April, Canada Coach Lines began bus service over this route. The station remained vacant after passenger service was discontinued and was demolished in 1958. Passenger service had long been unprofitable for the railway but their requests to end passenger service was continually denied by the Canadian Transportation Commission. In order to hasten the demise of the service, train schedules were purposefully set to frustrate the travelling public especially with respect to connections between the Lake Erie & Northern line with that of the Grand River Railway which travelled between Brantford, through Galt, to Kitchener. With the popularity of the automobile it was only a matter of time before passenger rail service was discontinued.

Train departing the Lake Erie & Northern station bound for Port Dover. Passenger service ended on the LE & N on Saturday 23-April-1955. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Passenger train service on Canadian National Railway’s Buffalo & Lake Huron Railway line between Fort Erie, through Brantford, to Stratford, was discontinued in 23-April-1960.

Street Name Changes

In 1958, a few street names were changed. St. George Road was renamed King George Road to avoid confusion with St. George Street. Brant Street in West Brant was changed to Sherwood Drive to avoid confusion with Brant Avenue. Burford Road was changed to Colborne Street West.

Industrial Developments

The City’s economy was closely tied to farm implements and textiles. After the post war boom, the manufacturing economy began to settle down. As the fifties wore on, lay-offs began to mount, by 1954 Brantford was the hardest hit community in Canada with over 4,000 people looking for work, in a City of 52,000. Employment began to slowly improve and in 1959 Massey-Ferguson’s employment peaked, just below the record levels of 1950, and Cockshutt’s situation was also vastly improved.

Massey-Harris built a new foundry, named the M Foundry, at its Verity complex in 1950. In August 1953, Massey-Harris merged with Harry Ferguson Companies to form Massey-Harris-Ferguson. The name was shortened to Massey-Ferguson in 1958. In 1956, the company purchased 118 acres of land on Park Road North and Henry Street as a reserve to eventually replace some of its older factories. In 1960, all production at Massey-Ferguson’s Market Street complex was discontinued and all personnel were laid-off. During the 1950s, Massey’s began to build factories in other countries and it became cheaper to manufacture the products produced at the Market Street factory overseas. The Market Street complex was one of the original Massey-Harris plants. The complexed was razed except for the warehouse at the north end of the property. The Brantford and District Civic Centre would eventually be built on the site.

Cockshutt faced a different situation. The stock of the company was undervalued. The company kept large reserves of working capital and cash to self-finance its expansion and thus paid small dividends. The company carried no debt. English Transcontinental, backed by American investors, began buying Cockshutt stock at depressed levels. By 1958, they had amassed over thirty percent of the company’s stock and demanded a reorganisation of the Cockshutt Board with English Transcontinental in control. The beginning of the end for Cockshutt began. The value of the company was less than the sum of its parts. The great dismantling and liquidation of the company would begin in 1960.

Changes at Brantford Cordage were also underway. The United Auto Workers organised the workforce and the family atmosphere at the plant began to dissolve. The UAW demands were greater than a textile oriented union more familiar with the industry made. It was clear to C.L. Messecar, owner and manager of the factory, that the union demands would disrupt the delicate balance of the cost structure of his business. Messecar sold the business to the Gairdner Group in Toronto, who combined it with Davis Leather Company of Newmarket, to form Tancord Industries. It was purely a financial play, to use the tax losses accumulated at Davis Leather to offset the profits from Brantford Cordage. Davis Leather closed down three years after the amalgamation.

In 1953, Gates Rubber announced plans to build a factory in Brantford; two years later it announced plans to triple the size of the plant. A.G. Spalding and Brothers announced in February 1954 that they would build a new plant in West Brant. The Brantford Screw Company purchased 50 acres in West Brant for a plant expansion at their Colborne Street West and Welsh Street facility. Canadian Westinghouse moved its radio and television division to the City in 1954. In 1959, Harding Carpets announced a major expansion to its Holmedale plant.

Canadian Westinghouse moved their television and radio division to a plant on Greenwich Street in 1954. Westinghouse closed this plant in 1971. The three and a half story building to the left is now Brant Instore and the foreground building is Ingenia Polymers. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

The Koehring Company of Cleveland bought the Waterous Company and brought the production of cranes and excavators to Brantford. In 1957, Koehring’s closed the foundry, dropped the sawmill equipment line of products and sold off the boiler products line. In 1959, an addition to the factory was made to accommodate the production of large forestry operations equipment.

Announcements of new plant openings and expansions were accompanied by plant closings. In 1952, the Canadian Car and Foundry malleable iron foundry on Usher Street was deemed surplus by its owner Avro Canada and production was moved to Montreal. The company’s buildings were quickly demolished and the land was sold to the CNR who built rail sidings. In 1959, Slingsby Manufacturing Company, located at 270 Grand River Avenue, suspended its operations putting 300 people out of work. Brantford Washing Machine Company, located at 16-18 Grey Street, closed as the company consolidated its operations in Toronto. Universal Cooler, located at 146 Sherwood Drive, shut down minutes before signing a new labour contract with the United Auto Workers, citing difficult union negotiations and poor expansion opportunities. The company moved to Barrie. Copeland Refrigeration Company moved into the vacated factory.

Canadian Car and Foundry plant on Usher St. It began as the Pratt and Letchworth Foundry in 1900. Pratt and Letchworth was a Buffalo based company. Canadian Car and Foundry purchased the plant during WWI. The foundry closed in 1952 and was demolished. The building marked A, the old pattern shop, is the only remaining building of this complex. It is now the location of Board of Your Flooring. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Slingsby Manufacturing Company Ltd Started by William Slingsby, a Yorkshireman, in 1872.The company grew from 15 employees to over 800 by 1947. The plant was located on Grand River Avenue at the foot of St Paul Avenue. Canadian Celanese of Montreal acquired the company on 13-February-1959. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

FitzJohn Coach of Canada In 1949, FitzJohn Coach of Canada was established by the FitzJohn Coach Company of Muskegon, Michigan, in an old hangar at the Brantford Airport. General Motors could not keep up with the post war demand for city buses, thus allowing smaller companies like FitzJohn to fill the void. The company started off strong in Brantford but faded after 1952. In 1958 the facility was sold to Blue Bird, allowing Blue Bird to expand into Canada. FitzJohn produced a total of 197 buses at the Brantford facility. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Expositor Building In 1950 the Expositor built a modern addition onto the west end of their existing building. When the $180,000 addition was completed the cupola and corner entrance would be removed. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Labour

Labour relations in the 1950s were not too tumultuous. A major strike at Cockshutt was averted in May 1950 with the assistance of the Ontario Labour Minister. The U.A.W. was able to get the work week reduced to 40 hours per week from 45 hours and provide fully funded pensions.

A strike at Harding Carpets, located at 85 Morrell Street, began on 23-August-1956 and lasted for 91 days. The Canadian Textile Council was seeking reduced weekly hours without a reduction in pay, an improved pension plan, and better medical coverage. There were verbal and physical confrontations on the picket line. Police were called to the picket line on a number of occasions. Violence peaked on 23-October when 40 policemen clashed with strikers who were supported by members from other unions, when they tried to clear the picket line to allow people to leave the plant. In the end, workers received a pay raise and improved pension and medical coverage, but not a reduced work week.

At Robbins & Myers, located at 58 Morrell Street, workers struck over wages and hours of work issues in 1959. This strike lasted 16 weeks.

Education

Lack of space in schools reached crisis proportions in the early fifties. Classes at Brantford Collegiate Institute were large, with up to 50 students in a class, classrooms were scarce, the student-teacher ratio was high, and the teachers faced a heavy workload. The City spent less on education than cities of comparable size in the province. Where the common practice was to allocate one-third of tax dollars to education, Brantford allocated one-quarter. In 1950, the Board of Education working with the City identified the Glebe lands on Colborne Street as a suitable site for a new high school and arranged a deal with Six Nations council to acquire the site. This site was the former location of No. 20, Canadian Army Basic Training Camp during World War II. Although Six Nations Council supported the land sale, ratification of the agreement by the reserve residents was necessary and the voters on Six Nations did not ratify the agreement.

The Board of Education needed to find another site. Twelve locations were considered including the Arrowdale Golf Course, Mohawk Park, and a portion of Mount Hope Cemetery. In 1951, the Board opted for a 12 acre Mohawk Park site but then balked at the price the City asked for. In the meantime, with no site yet selected, attendance at BCI had reached 1,400, in a school designed to hold 900. In 1952, the School Board built an eight-room annex behind BCI to alleviate some of the overcrowding. The Board returned to the Glebe site as their preferred choice. In February 1953, the Six Nations voters agreed to sell 90 acres of the Glebe property to the Board of Education for $160,000 and the right to name the school. Pauline Johnson Collegiate Institute opened in January 1955 but this second high school did nothing to alleviate the overcrowding in the vocational department of BCI. Vocational subjects were going to be needed at Pauline Johnson.

Enrolment continued to rise in the high schools and it was clear a third high school was needed. In 1956, the Board decided to build a third high school on Wood Street, between what is now Metcalfe Crescent and St. Paul Avenue. Even though the Board was now moving quickly to begin construction of the third high school, BCI and Pauline Johnson were over capacity and the expectation was that the new school would still not provide enough space to accommodate all the expected 2,700 students. The Wood Street site would have to be abandoned when the School Board learned that the Department of Highways planned a four-lane highway behind the school, depriving the school of any campus space. A new location on North Park Street was identified and construction began in 1957. North Park Collegiate did not open until January 1960 which necessitated the implementation of a shift system at BCI to accommodate all the students. BCI student attended the school in the morning and North Park students attended in the afternoon. An addition to Pauline Johnson was also underway and would open in the spring of 1960.

Drawing of Pauline Johnson Collegiate as it appeared on the cover of the 1956-57 yearbook - Owanah. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

The Brantford Catholic High School moved into the former Cockshutt Estate on Dufferin Avenue in 1951. The high school opened in 1941 in the basement of St. Ann’s Catholic School on Pearl Street with one grade nine class. A new class was added every year until 1951. An addition was made to the school in 1958 and the school’s name was changed to St. John’s College in 1959. The Dufferin Street campus remained in use until 1981 when expansion of the former Providence College campus was finally able to accommodate all students at one site.

Elementary schools were also under pressure. Between 1945 and 1952, elementary school enrolment increased by over 1,000 students. The Brant County Board of Education went on a building spree. Fairview Memorial School, located at 34 Norman Street, opened in 1947. In 1988, the school was converted to house alternative and special education classes. In 1992, it became a French-immersion school, École Fairview. The school closed in June 2016. Prince Charles School, located at 40 Morton Avenue, opened in 1949. In 1953, Thomas B. Costain School, located at 16 Morrell Street, opened. Costain returned to Brantford to officially open the school. Coronation School on 54 Ewing Drive opened in 1954. The school closed in June 2014. It reopened in September 2016 as a French-immersion school, École Confederation. F.C. Bodley Public School, located at 365 Rawdon Street opened in 1955. Bodley was the architect of more than a dozen City public schools built between 1924 and 1960. The last school Bodley designed for the Brant County Board of Education was North Park Collegiate. F.C. Bodley School closed in June 2006. Agnes Hodge Public School, at 52 Clench Street, opened in 1956. It was named after the women who organised the City’s first Home and School Association. Woodman Drive Public School, located at 51 Woodmand Drive, and Oak Hill Drive School opened in 1958. Oak Hill Drive School closed in June 1983. Greenbrier School opened in 1960.

The Board tried other ways to alleviate overcrowding. In 1959, the first portable classrooms to be used in the City were installed at Prince Charles Public School and Fairview Public School.

The Catholic Board of Education was also busy building four new schools. Our Lady of Fatima, located at 120 Ninth Avenue, opened in 1954. It closed in 2009. St Pius X School on Wood Street was built in 1954 and doubled in size in 1956. The school closed in June 2012, was razed, and rebuilt, opening in September 2013. Holy Cross School, at 358 Marlborough Street, opened in 1958. St. Theresa School, located at 12 Dalewood Avenue, opened in 1959.

St. Pius X School on Wood St in 1954. The school built an addition in 1956 to double the number of classrooms. In 2012 the school was razed and rebuilt, opening in September 2013. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

In 1951, a Royal Commission Report on Education found the conditions at the Ontario School for the Blind, renamed the W. Ross MacDonald School in 1974, deplorable. The report found the school building to be …inadequate, antiquated, dilapidated, dismal, poorly lit and constitute a fire hazard of the first order…. After the report was released, the Ontario Department of Education quickly announced plans to update the older building and build a new junior school.

In 1951, salary arbitration was used for the first time in Ontario when forty of the fifty teachers at BCI submitted their resignations in protest of the salary being offered them. The teachers were awarded an increase of $800.

Public Health

By 1952, the Grand River was known as The Grand Sewer and was reported to be one of the six worst polluted rivers in North America. Brantford was the only large centre located on the Grand River without any type of treatment plant even though residents voted for the construction of a primary treatment facility in 1946. Concerned about the condition of the river and the implications to the health of Brantford residents, the Board of Health began lobbying the Provincial Board of Health to force Grand River communities to build sewage treatment plants. In October 1957, engineers determined that a primary and secondary sewage treatment facility would cost $2.9 million. The City was financially prepared to build a facility because it had been collecting a special tax for this purpose since 1946. Construction began in 1959 and the facility was officially opened on 7-September-1960.

It should come as no surprise to the reader that the conditions at the Brantford General Hospital were terrible and dangerous. The wards were overcrowded and sunrooms and corridors were being used to house patients. The nurse’s dining room and the kitchen facilities were inadequate. The hospital only had two and a half operating rooms when six were needed. A 1951 Grand Jury report found the original hospital building to be: obsolete in design and function as well as presenting a very dangerous fire hazard. The recommendation was to demolish the building as soon as possible. The Hospital had been running a deficit since 1934 so this impacted their ability to modernise and upgrade the facility. The Grand Jury recommended that the Hospital reorganise itself with a focus on administering the hospital more like a business. In May 1952, the Hospital appointed a business administrator and finished 1954 with a surplus.

Between 1945 and 1950, hospital admissions doubled. The increase in admissions was attributed to an increase in the City’s population, new health insurance schemes, and a declining fear of hospitals amongst the public.

Drastically improved facilities for the City were required. The Hospital Board considered extensions to the existing building, a new hospital in the Township or across the street from the current facility, and even a private hospital. But the Board was split on how to proceed in spite of a dire need for action. The catalyst to action came by way of the Sisters of St. Joseph who proposed a new 150-bed hospital in the City. The Brantford General Hospital now had competition for funding. The Board quickly proposed a $2.8 million plan for a six-storey addition and the modernisation of the Hospital. In 1954, taxpayers voted to support the plans of both hospital groups with the BGH getting $1.8 million dollars and the Sisters of St. Joseph, $1 million.

Brantford General Hospital after the completion of the rebuild in 1960. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

St. Joseph’s Hospital, a 135-bed facility, opened on 15-August-1955. In December 1955, work at the BGH would begin on Wing A, the Westview Pavilion. It officially opened on 1-June-1957. In 1959, Wing B, the John H. Stratford Pavilion, opened. Amidst all the planning for the expansion of the BGH, Wing B was designed with no elevators. An oversight no one caught.

St. Joseph’s Hospital in 1955 on what was then Park Road North. The building has been repurposed to St. Joseph’s Lifecare, a long-term care facility. St Joe’s closed their maternity ward in June-1972. The Ministry of Health closed the hospital 2001. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Nursing school was provided at the BGH but the residence for nursing students was located at Winston Hall in Eagle Place (124 Ontario Street), not conveniently located to the Hospital. Winston Hall was built as a residence for war workers. It was designed as a temporary structure to be taken down after the war but was pressed into continued service because of the housing crisis in the City. A new nurse’s residence was desperately needed. Remember the fear City Counsellor’s had regarding building cheap temporary war time homes mentioned in my earlier columns? Their concern was that the homes would not be dismantled but continued to be used and become unsightly. This example demonstrates that their concern had merit. A new nurse’s residence would not open until 1964. It was built on BGH property south of the hospital.

To alleviate some of the overcrowding at the Brantford General, Alderman John Noble proposed a hospital for the chronically ill, on the grounds of the Brant County Home for the Aged and Infirm. Noble made it clear the facility was not a hospital but rather a care facility. In November 1954 a new 80-bed facility opened. It was named the John Noble Home.

Newly opened John Noble Home in 1955. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Arena / Performing Arts Centre

In 1950, Mayor Howard Winter declared that the construction of a new arena would be a priority for the City. Brantford needed a modern facility if it was to compete with neighbouring municipalities as a desirable place to live. A bylaw was prepared to issue $650,000 in debentures for the construction of a multi-use building to be built on the canal basin, where the Farmers’ Market is today. The building would house a 1,200-seat auditorium, banquet hall, and an arena seating 5,000 for hockey and 7,000 for concerts. The community felt there were more pressing issues, a sewage treatment plant, new schools, and a new hospital, and defeated the bylaw, but by only 374 votes.

In 1953, Brant Arena Limited proposed to erect a privately owned 3,500 seat arena and multipurpose facility at the entrance to Mohawk Park. The company abandoned its plans one year later.

As discussions and proposals for a new arena and civic centre made headlines during the 1940s and 1950s, the Arctic Arena deteriorated. The Arctic Arena’s owner was reluctant to invest in the arena, the City’s only indoor artificial ice surface, because of the expected construction of a municipally owned facility. In May 1959, the arena building was condemned as a fire hazard and closed. That left the City with only two outdoor artificial ice rinks at Lions Park that were constructed in 1954. In 1958, the City’s Planning Board recommended a site for the arena on Wood Street, between what is now Metcalfe Crescent and St. Paul Avenue, where North Park Collegiate was first planned to be. Edmund Cockshutt, in addition to leaving his Glenhyrst estate to the City, left $5,000 towards the construction of a new arena as long as construction commenced by January 1959. As the 1950s closed, Brantford did not have an indoor artificial ice arena.

In the 1950s, the Paramount and Capitol Theatres were the only concert hall venues in the City. The Rotary Club lobbied for a multi-purpose auditorium to be included in the design for one of the new high schools. The Board of Education supported the proposal but was not willing to assume any financial burden for the auditorium and the idea died.

The Odeon Theatre, located at 50 Market Street, opened on 17-December-1948. The opening film shown was Blanche Fury starring Valerie Hobson and Stewart Granger. The Brant Theatre, located at 77-79 Colborne Street, was purchased by Paramount Theatres Limited in 1951 and renamed the Paramount Theatre. It closed in 1960. The Esquire Theatre, located at 65 Colborne Street closed on 25-July-1955. The 982-seat theatre opened in 1937. The building was demolished in July 2010 along with the rest of the south side of Colborne Street, between Market Street and Brant Avenue. The 447 seat College Theatre, located at 310 Colborne St, opened in 1939. The theatre closed in 1956 but then reopened in 1957 before closing for good in 1962. After the theatre closed it became the Talk of Town Billiards; it is now the 310 Sports Bar & Grill.

The Breezes Drive-In Theatre on Powerline Road opened on Saturday 22-May-1954. The theatre was built on a 12-acre site and accommodated 500 cars, but had room for an additional 1,000 cars. The screen measured 48 feet wide by 40 feet high and was designed to handle CinemaScope when it became available with the addition of wings to the edge of the screen. The theatre featured baby-bottle warmers to encourage families with babies to get out for a night. The theatre opened showing the 1951 film, I’d Climb the Highest Mountain, starring Susan Hayward and William Lundigan, and the 1948 film, When My Baby Smiles At Me, starring Betty Grable and Dan Dailey.

Arts and Culture

Lorne Greene, Mel Tormé, Gracie Fields, Glen Gould, the National Ballet of Canada, and Barbara Ann Scott all visited Brantford in the 1950s. Barbara Ann Scott skated in front of a packed house of over 2,000 at the Arctic Arena in 1950. Scott won a gold medal for Canada in figure skating at the 1948 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Switzerland.

The Universal Mixed Choir placed first at the Chicagoland Music Festival in 1952, the second time a Brantford Choir achieved this distinction. In 1949, the Universal Ladies’ Mixed Choir placed first. The Cockshutt Male Choir disbanded in 1957. The choir performed in 180 concerts before more than 60,000 people over its 22 years.

Cockshutt Male Choir in 1950. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Edmund Cockshutt willed his estate, Glenhyrst Gardens, to the City in 1951 with the proviso that the grounds be used as a horticultural centre and the residence as an art gallery. Cockshutt passed away in 1956 and the art gallery, now known as Glenhyrst Art Gallery of Brant, opened in 1957. With this gift, Brantford became the only city in Canada to own its own building dedicated to art, crafts, and hobbies.

Edmund Cockshutt built his estate at Glenhyrst in 1922. The mansion was designed by Brantford Architecture F.C. Bodley. Cockshutt donated the estate to the City of Brantford upon his passing in 1956. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

The Brant Historical Society opened the Brant County Museum in their new location at 57 Charlotte St in June-1952. The nucleus of the Society was formed in 1890. Its small collection was housed in the library which at the time was located in what is now Royal Victoria Place at the corner of Dalhousie and George Streets. The Brant Historical Society was formed at a meeting held on 11-May-1908. The Society operated a museum in the Carnegie Public Library until it bought its own property in 1951.

Brant County Museum in 1960. The Aboriginal Mask was added over the front door in 1959. An addition was added to the north side of the building (left side) and opened in November-1966. The Mask was removed from the museum in 1996. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Sports and Recreation

Mohawk Park declined during the decade. The track was now used for stock car racing and the grounds and buildings were badly in need of maintenance, yet the park proved popular with residents attracting over 100,000 visits during 1955. During the 1950s, City Council considered selling some of the park for Pauline Johnson Collegiate, using some of the park for a new arena, and selling some of the land for residential development. In 1956, the City spent $5,000 to clean up and beautify the park. Vandalism, drinking, and rowdyism at the weekly dances in 1959 caused the City to padlock the concession stand and dance pavilion in September.

Mohawk Park Dance Pavilion. Vandalism, drinking, and rowdyism at the weekly dances in 1959 caused the City to padlock the concession stand and dance pavilion in September. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Agricultural Park was renamed Cockshutt Park in 1957, after the Cockshutt family who donated the 19-acres of land to the City in 1901.

Earl Haig pool was overhauled in 1956 after water from the Grand River began seeping into the pool.

Earl Haig Pool, ready for the summer season 1955. The pool opened 7-July-1923 in Swimming Pool Park. The park was renamed Earl Haig Park in 1929 at the request of the Canadian Legion. The pool was closed in 1930 due to a spinal meningitis outbreak and remained closed until 1942 because of the difficult financial times the City was experiencing. The pool was overhauled in 1956. In 1982 the site was rebuilt and renamed Waterfront Park. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Bowling gained in popularity and four new suburban lanes opened in the 1950s. Brantford had two bowling alleys downtown. In 1953, Echo Lanes at 750 Colborne Street and Star Lanes at 144 Mary Street opened. North Star Lanes, at 61 Charing Cross Street opened in 1959. Mohawk Bowl, next to Pauline Johnson Collegiate, in the Mohawk Plaza opened in 1960.

The Esquire Theatre was constructed in1937. It sat 982. The theatre was built in the Art Deco style and featured a Thunderbird centred over the second storey. The ground floor was clad in Vitrolite, an opaque pigmented glass. The theatre closed in 1955. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

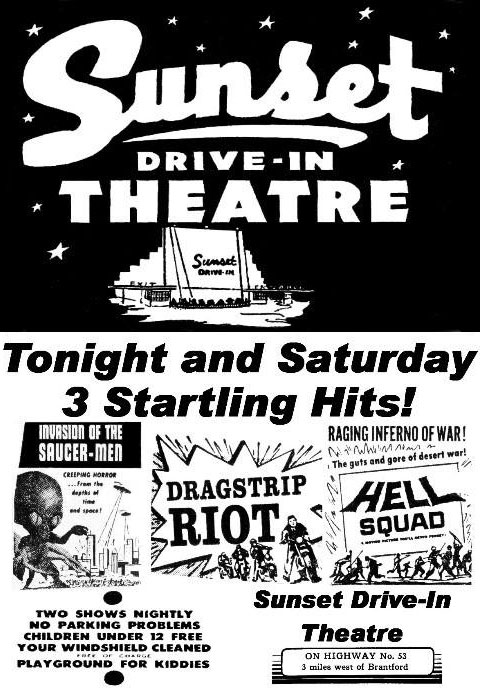

Sunset Drive In newspaper ad from 1958. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Northridge Golf Course opened in 1957 and the debate began about closing Arrowdale Golf Course and using the land for housing. It was decided to allow Arrowdale to operate for one more year. Arrowdale is still open and the debate over its future continues, 60 years later.

Brantford Golf and Country Club clubhouse from the early 1950s. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

The Brantford Nationals won the Ontario Senior B hockey title in 1950 and again in 1951 under the name the Brantford Burtols. The team moved up to Senior A in 1952 but had to withdraw from the circuit in 1953 because the Arctic Arena was not large enough to seat the crowds needed to support the team financially.

Brantford’s tradition of fielding competitive basketball teams started early. Men’s and Women’s teams won several Ontario titles and in 1957 the Bel-Aires won the Canadian Senior B Ladies basketball championship.

After winning the 1949 Senior Intercounty Baseball League Championship, the Red Sox lost the 1951 championship in seven games. Baseball was popular in Brantford and fan support was very good during the early 1950s. Support waned in the mid-fifties and the team almost folded in 1955. However, by the end of the fifties fan support had returned and the Red Sox won the 1959 title, the first of six championships in seven years, winning five titles in a row. In 1957, the Parks Board rescinded its permission to allow Sunday baseball games to be played at Cockshutt Park. The Sunday sports debate would rage for four years.

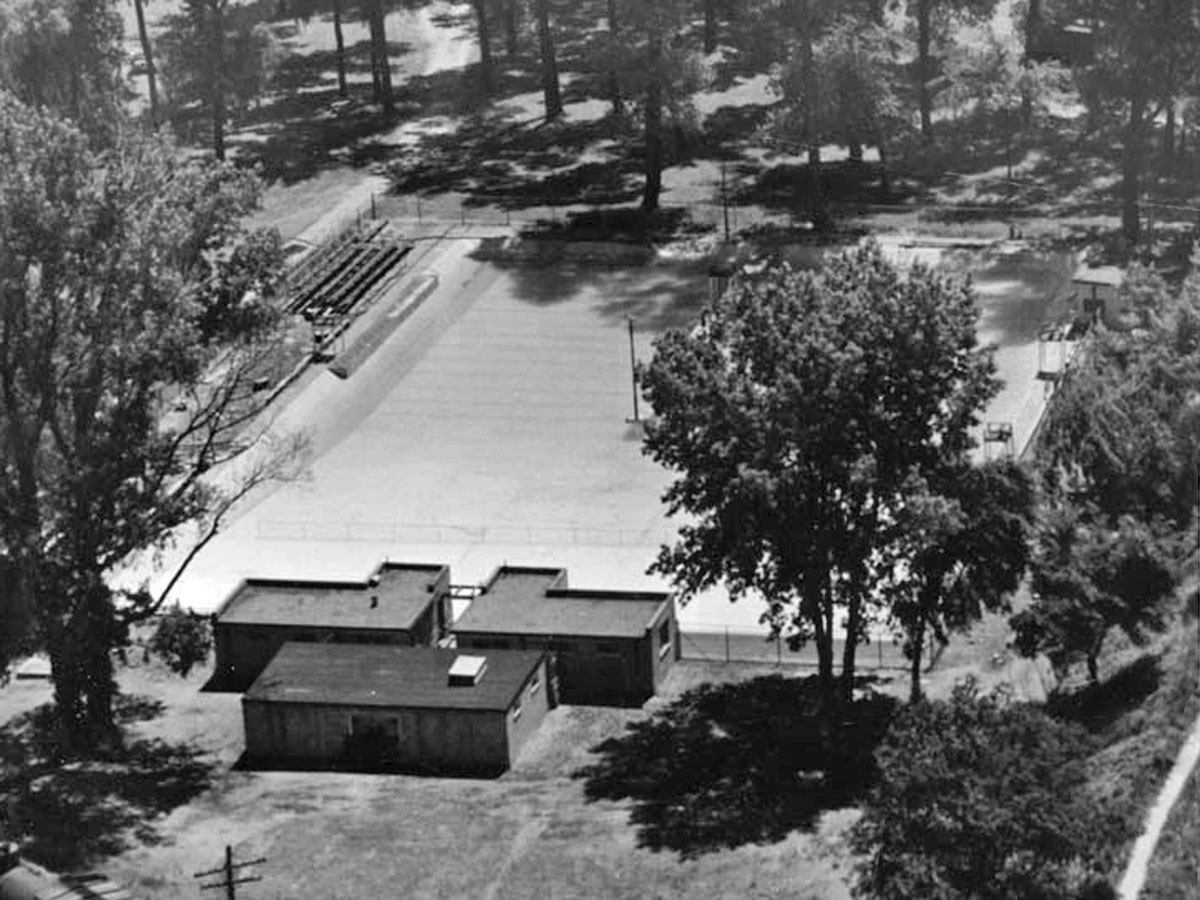

Watching the Brantford Red Sox practice at Cockshutt Park in the spring of 1954. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Jimmy Wilkes was an outfielder in Negro League Baseball between 1945 and 1950. He spent two years in the Brooklyn Dodger organization before joining the Brantford Red Sox of the Intercounty Baseball League in 1952. He settled in Brantford and worked for the City. He helped the Red Sox win five consecutive Intercounty titles between 1959 and 1963. He continued as an empire in the Intercounty league for another 23 years. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Football struggled in Brantford for fan support although the 1957 Brantford Tiger-Cats made it to the Eastern Canadian final in the Intermediate Ontario Rugby Football Union.

Gord Wallace achieved success in the boxing ring upsetting British champ Ron Turpin in the light-heavyweight class in 1955 and defeating British boxer Ron Barton for the British Empire light-heavyweight championship in 1956.

Gord Wallace became the British-Empire light-heavyweight boxing champion in 1956 defeating British boxer Ron Barton. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Swimmer Sara Barber represented Canada at the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Vancouver. At 13, she was youngest athlete at the competition. Sara competed in the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, and the 1960 Olympics in Rome. Sara also competed in the 1958 and 1962 British Empire and Commonwealth Games and the 1959 Pan-American Games.

Piston Pushers

In the early 1950s, a group of young men began hanging out over their mutual love of cars. They would cruise downtown and race on weekends. In December-1953 they met to discuss organising a club. Piston Pushers was formed in June-1954. In 1955, they registered their club, elected an executive, and started to hold regular meetings at the Starlight Dance Hall on Colborne Street at Locks Road. They called themselves Piston Pushers. There were 14 original members. They wore red jackets with white lettering. Shake N Burger, Koster’s Drive-In, S&S Root Beer and A&W became favourite hangouts. They opened their first clubhouse in 1956. In 1958, they moved into a former Esso station on Highway 2 beside Fairchild Creek and remained there for 25 years. The Piston Pusher name on the building was well known to motorists travelling between Brantford and Hamilton. Although no longer their clubhouse, the old building on Highway 2 remains standing.

Piston Pushers’ long time club house on Hwy 2 & 53 located next to Fairchild Creek. The club occupied the building for 25 years. The building still stands. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

The Proliferation of the Automobile

After the war as the economy returned to peacetime production, the automobile became the centrepiece of the growth of the economy. Cars were cheap to operate and the burgeoning highway network was enticing to the motorist, especially because there was a concerted effort to convert the highways to hard-surface, all-weather roads. As the population took advantage of their new-found freedom of movement, motels started to be built along the highways to accommodate travellers, replacing the cabins of the 1930s and the downtown hotels. Motels offered parking at your door.

Highway 2 was the major east-west thoroughfare in Ontario until Highway 401 was completed in the late 1960s, and the highway between Brantford and Hamilton carried a high volume of traffic. The first motels in the City were built along the eastern end of Colborne Street. The first motel was built by H. Sumler at 950 Colborne Street. It became known as the Beauview Motel in 1954, then later the Twin Gates Motel. It is now known as the Galaxy Motel. Next came the Gage Motel at 568 Colborne Street in 1951, followed by the Bell City Motel at 901 Colborne Street, in 1953, The Mohawk Motel located at 769 Colborne Street, in 1955, the Sherwood Motel at 797 Colborne Street, in 1959, and finally the Brant Motel, 780 Colborne Street, in 1960. Of all these motels only the Brant Motel no longer exists.

Beauview Motel, the first motel in Brantford, opened by H Sumler on Colborne St E. For years it was known as the Twin Gates Motel. It is now known as the Galaxy Motel. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

The Mohawk Motel opened in 1955 on Colborne St E. It is still operating today under its original name. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

The Sherwood Motel opened in 1959 on Colborne St E. It is located adjacent to the Sherwood Restaurant. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Improved roads also supported the development of suburbs adjacent to existing cities. Since these suburbs were located farther from the downtown commercial areas and were not serviced by city buses, suburban plazas began to be built to cater to the needs of the people in these new subdivisions. The demand for parking spaces downtown exceeded the supply, and downtown was congested with traffic. The suburban plazas featured big new stores, were easy to get to, and offered free parking. The new subdivisions were carefully planned with separation between residential and commercial areas, which meant that a car was a necessity to travel to these plazas.

The first suburban plaza was built by Loblaws at the gore of St. George Road, now King George Road, and St. Paul Avenue, in 1953. This store was known as a Super Market and was two to three times the size of a grocery store of the period, 10,000 to 12,000 square feet as opposed to 3,000 to 5,000 square feet. The A & P built two stores, the first one in 1953 on St. George Road, opposite Elmwood Avenue, and the second store in 1956 at Dalhousie and Stanley Streets, where the McDonald’s restaurant is today. Grand Union opened at the Mohawk Plaza, next to Pauline Johnson Collegiate on Colborne Street, in 1956. The store became a Steinberg’s in 1958. The location eventually became a Calbeck’s and finally a Price Chopper. It is now the location of Brantford Surplus. Dominion Store opened their new modern super market on St. Paul Avenue and St. George Street in 1959. Calbeck’s had two locations, at 61-73 Murray Street, and at 106-108 Colborne Street West, which opened in 1951. Calbeck’s first used the term super market to describe their stores in 1954. In 1955, the Colborne Street West store was called Super-Save and the Murray Street store was an IGA. The Murray Street store was branded Super-Save in 1957. Gordon’s Groceteria at 67 Erie Avenue became Gordon’s IGA in 1956, then Gordon’s Red and White in 1960. In 1965, a new store was built at 43 Erie Avenue. It was first known as Gordon-Guscott’s Foodmaster, and then later Gordon-Guscott’s Super-Save. The IGA Foodliner opened at the Pleasant Plaza Shopping Centre at 164 Colborne Street West, at Welsh Street, in 1960.

Loblaws was located in the first suburban plaza built in the City in 1953, on King George Rd and St Paul Ave. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

The Grand Union Super Market opened in February-1956. It was located next to Pauline Johnson Collegiate. The super market became a Steinberg’s in 1958. The plaza was built out in the late 1950s adding the TD Bank and the Shake ’N Burger in 1959 and Mohawk Bowl in 1960. Today the store is occupied by Brantford Surplus. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Minard-Gerow Pharmacy, the first modern drug store in Brantford opened on St. Paul Avenue at Dublin Street in 1956. It was located in one the first suburban strip malls in the City across from the new Loblaws Super Market.

Minard-Gerow Pharmacy, the City’s first modern drug store, opened in 1956 on St Paul Ave at Dublin St kitty corner from the new Loblaws. Image courtesy of Sheila Minard

Drive-In restaurants also started to appear, again catering to the motoring public. George Koster opened Koster’s Cream-EEE-Freeze on Brant Avenue and Bedford Street in 1953. In 1965, the building was moved to the Brantford Plaza on King George Road and the name was changed to Dairee Delite. Koster also opened a drive-in on Highway 2, Koster’s Drive-In. Dairy Queen opened two locations in Brantford. The Echo Place outlet at 930 Colborne Street was the seventh Dairy Queen in Canada. It opened in 1954. The second outlet opened in 1955 at 113 St. George Road, now King George Road. In 1956, Mac’s Drive-In opened at 666 Colborne Street. It became Nick’s Drive-In in 1957 and Bill’s Drive-In in 1960. Stan Bielick opened the Shake ’N Burger at the Mohawk Plaza on Colborne Street in 1959. The Shake ’N Burger featured a drive through take out window. To eat on site, the driver turned on their headlights and a cowgirl roller skated to your car to take and deliver your order. The Quikee Drive-In opened in 1959 on Colborne and Puleston Streets. The business became Robertson’s Drive-In in 1961 and was later rebranded Robbies. Robbies' King George Road location, next to Loblaws, opened in 1965.

Koster’s Drive-In was one of the early drive-ins established just outside the city. Koster’s was located next to what is now the Crossroads Antique Market, formerly the Cainsville Mall, 1146 Colborne St E. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

The Cres-Mar Dining Lounge became the Pow Wow Drive-In on Hwy 2 & 53 to Hamilton. It is now the China King Restaurant, 1320 Colborne St E. Image courtesy of the Brant Historical Society

Of local interest, the Shanghai Restaurant opened as the Shanghai Chop Suey House at 89 Colborne Street in 1956. The Oriental Restaurant opened at 104 Market Street, next to the Bell Telephone Building in 1960.

In 1957, the Cainsville Post Office closed. It was established in 1854. Roy Pierson was the retiring postmaster.