Brantford in the 1990s - Post 23

By the end of 1980s the City was optimistic. The 1990s was predicted to be Brantford’s decade. New civic projects were progressing, over 100 new companies had set up shop in Brantford since 1985, and real estate brokers reported that there was an increasing number of people looking to move to and settle in Brantford. Brantford had turned a corner and was confidently expecting an improving economy.

The Economy

The North American economy was plunged into a recession in the early 1990s. Some of the reasons cited were: the end of the Cold War leading to a decrease in military spending; restrictive central bank monetary policies in response to rising inflation; the rise in oil prices from $17 per barrel in July-1990 to $36 per barrel in October-1990 because of the Persian Gulf War; Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait; and a decline in real estate development because of overbuilding during the 1980s.

Brantford was hit hard during this recession. By February-1991, over 7,000 people in the City and County were collecting unemployment insurance, an increase of almost 2,200 people from the year before; this was the highest level in seven years. People on welfare reached 2,570, an all time high; more than 1,200 higher than the year before. Food bank usage soared causing the food bank to use some of their reserve funds. At the end of 1991, over 20,000 people had used the food bank, almost double from the number in 1990. The line-ups at the Blessing Centre soup kitchen got longer as the year progressed, the United Way did not reach its fund-raising goal, the number of people filing for bankruptcy increased substantially, and unpaid taxes were at their highest level ever.

The Brantford Blessing Centre was founded in 1982 to provide food and basic necessities to residents in need. Anyone is welcome for a hot meal, warmth, and fellowship. Volunteers prepare, cook, and serve meals six days a week. The Centre is supported by the following churches: Bethel Reformed Church, Central Presbyterian Church, Cornerstone Church, Evangel Pentecostal Church, Grand Valley Christian Centre, Grace Free Reformed Church, Life Quest Church, Living Water Reformed Church, New City Church, New Life Church, and Church of the Nazarene. (photo by the author)

1992 was even worse than 1991. 27,500 used the food bank. The recession put tremendous pressure on Social Services requiring considerably more funding than the previous year. The demand for affordable housing was at crisis proportions with over 850 people on the Housing Authority’s waiting list in 1993. Brantford was much worse off than other communities in southern Ontario. The hard times in Brantford made the front page of the New York Times on 3-October-1993. The writer blamed the free trade agreement with the United States which resulted in the City undergoing a transition similar to what other manufacturing centres were experiencing. Manufacturers found that they no longer needed a plant in Canada if American products could move across the border duty free.

The Brantford Food Bank began in the late 1980s because of the economic hardship that hit the city. It was originally called the Brantford Unemployed Help Centre. In addition to helping families and individuals in Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations they provide a food distribution service to 26 other food and meal providers in the community.

The local economy began to improve in 1993. The unemployment rate in November-1993 was 10.7 percent, down from 14.7 percent in March-1993. The economy gradually improved throughout the 1990s. It is interesting to note that in September-1999 The Manpower Employment Outlook, an international magazine, rated Brantford last for employment prospects in a list of 44 cities, yet three month later Brantford was noted as one of the most promising job markets in Canada. It can make one question just how credible are these lists?

Industry

The City’s industrial landscape continued to evolve. Old companies of the past were replaced by new, smaller companies moving to town. By the mid-1990s the following companies were gone: Trailmobile (Fruehauf Canada), Solary, Chicago Rawhide, Timberjack (Koehring-Waterous), Robbins & Myers, Brantford Roofing (Northern Globe), and Barber-Ellis (Innova Envelope). These companies left or closed because of amalgamation, free trade, restructuring, or outdated equipment. In 1994, BASF on Craig Street closed as did TRW Automotive Electronics Group. TRW employed 180.

Trailmobile began in Paris in 1863 as Adams & Son, and later the Adams Wagon Company. It moved to Brantford in 1900. Cockshutt acquired the business in 1911 and renamed it Brantford Coach and Body. In 1960 a new plant opened in the Cainsville industrial park. Trailmobile Canada acquired the company in 1968. The plant closed in July-1990. (photo by the author)

Timberjack began in 1844 when Phillip VanBrocklin opened Brantford Engine Works. The company was renamed C.H. Waterous and Company in 1864 and then Waterous Engine Works in 1874. It was acquired by the Koehring Company in 1953. Timberjack acquired the company in 1988. It closed down in October-1992, the oldest Canadian company in continuous operation when it closed, 148 years. (photo from Pinterest)

Barber-Ellis moved to Brantford from Toronto in 1904. The factory was located on Marlborough Street at Park Street. The company manufactured envelopes, printing papers, and stationery. The company moved to Plant Farm Road in 1990. Now known as Innova Envelope, it closed in August-1996. The original factory site was partially demolished and converted into condominiums by Multani Customs Homes. (photo by the author)

This building located on Craig Street and Morton Avenue East was the site of BASF and later Nu-Gro. The site was the preferred location for a Costco store in Brantford but the location was rejected by the Ministry of Transportation because setback requirements for highway 403 could not be met. Costco is planning to build on the property of Lynden Park Mall (photo by the author)

In 1990, Calbeck’s was sold to Sobey’s. Calbeck’s was Ontario’s largest family-owned grocery-store chain at the time; it had seven stores. Agnew-Surpass moved to London in 1992 and went bankrupt in 2000; it started in Brantford in 1879 as Agnew Shoes and merged with Surpass stores in 1928. Brant Dairy, which started in 1921, was sold in 1995 to Agropur of Québec. Brant Dairy, continued to operate on Elgin Street.

Reg Calbeck opened his first store on Colborne Street West in 1921; first as a bakeshop but soon thereafter changed it to a grocery store. Calbeck’s began to expand in 1956 under the leadership of Arthur (Reg’s son) and Jack Calbeck (Arthur’s son). Calbeck’s grew to seven stores - three in Brantford, and one each in Paris, Waterford, Simcoe, and Port Dover. Calbeck’s was sold to Sobey’s in 1990. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

Keeprite began operations in Branford in 1945. In 1983, Keeprite was the largest manufacturer of air conditioners in Canada. The company was acquired by Inter-City Gas Ltd. Because of restructuring Inter-City moved production from their Illinois plant to Brantford in 1991. Rather than doubling employment at the plant as the company had expected, a weakening of the market saw the plant lay-off workers. In January-1994, the Brantford plant closed costing 765 workers their jobs.

American Healthcare Manufacturing, formerly Texpack, went into receivership in March of 1992. A buyer was found and the union agreed to a new contract but the Ontario Development Corporation, who held loans on the company, didn’t believe the plant was viable causing the buyer to walk away from the purchase after objecting to the conditions set by the ODC. 190 people lost their jobs.

Harding Carpets died a slow, agonising death over eight years. A failed joint venture with a Tennessee company in 1990 almost led to the end of the company, but the Ontario Development Corporation provided loans and loan guarantees to keep it afloat. Sales increased fifty percent between 1991 and 1993. In 1994, National FibreTech bought the company. By 1997, the company was overextended and declared bankruptcy. The plant closed in May-1997. The employees tried to buy the plant and reopen it financing the purchase using money owed to the workers by the company in unpaid benefits. This proposal would result in the unemployed workers having their unemployment benefits clawed back, so the plan was abandoned. Another group surfaced in 1998 with a plan to begin production in April but their financing never materialised. The plant closed for good in August-1998 and the production equipment was auctioned off.

Gates Rubber, the City’s largest employer in 1990, expanded their operations in 1990, and again in 1992 and 1994. A slowdown in the U.S. automotive market resulted in lay-offs in 1995 and 1996. In 1999, the company closed its Iroquois Street manufacturing factory. The company still operated a facility on Henry Street.

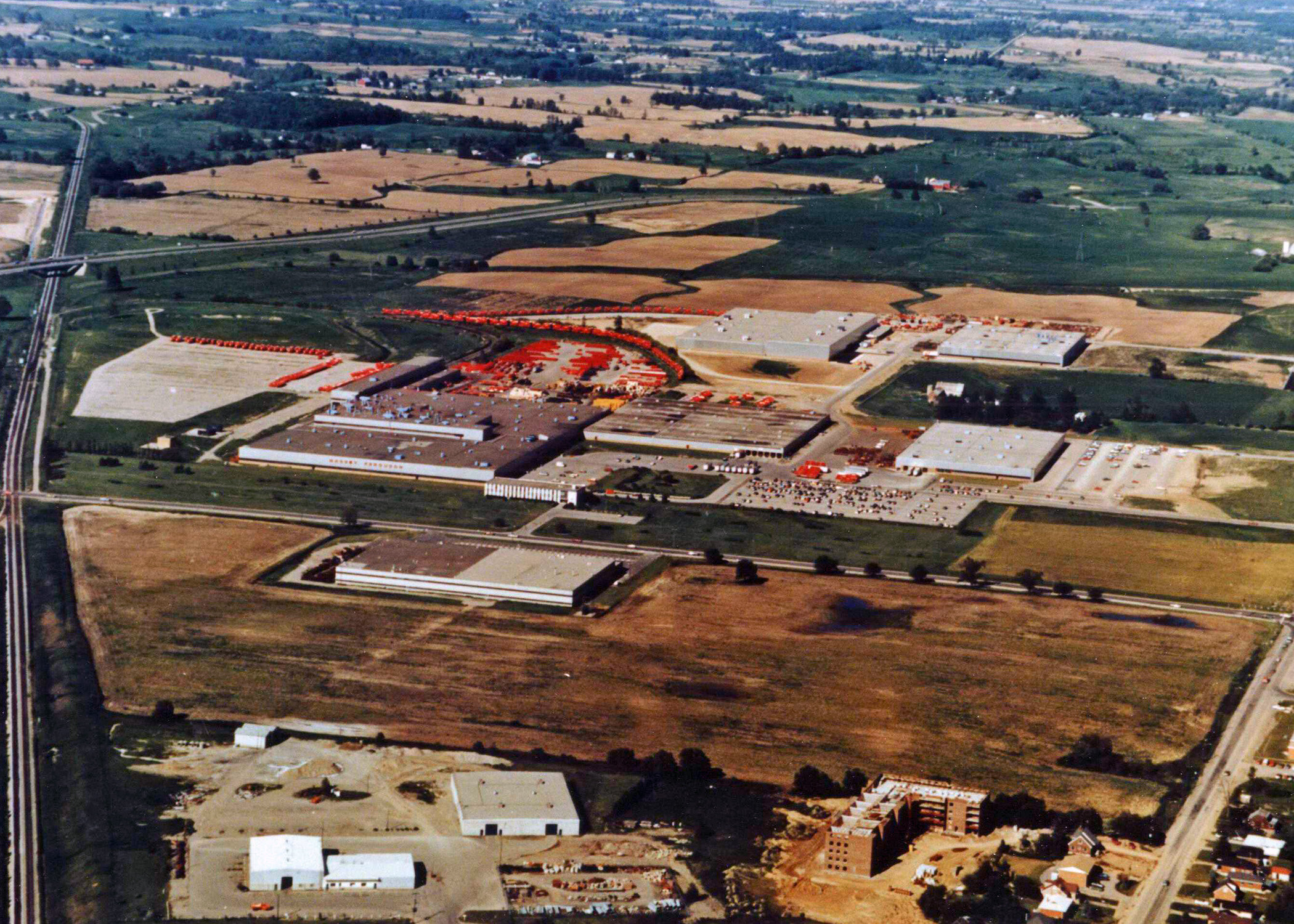

On the good news front, the City attracted 17 new companies to town in 1990. By the end of 1994, all the space at the former Massey-Ferguson North American combine plant was occupied. This complex was renamed the Brant Trade and Industrial Park. SC Johnson and Son saw a significant increase in sales by giving the Brantford plant a North American mandate for certain products, taking advantage of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement. This resulted in a near doubling of production staff by 1994.

The City was able to attract auto parts manufacturers. Standard Tube of Canada and Utilase Blank Welding Technologies arrived in 1997. In 2000, Meridian Automotive Systems announced their intention to move to Brantford and Wescast Industries announced it was building a technical centre and head office in the new Northwest Industrial Park.

By 1999, the unemployment rate was down to 5.8 percent. The National Post Business Magazine rated Wescast Industries, Eagle Precision Tools, and Nu-Gro among the best business performers in the country. None of these companies have manufacturing facilities in Brantford any longer.

Northwest Industrial Park

In 1991, the City purchased 200 acres to create the Northwest Industrial Park, at Oak Park and Hardy Roads. More land for industrial development and expansion was needed by the City. The idea was to service the land with sewer and water connections through West Brant and along the river bed of the Grand River, upstream from the water intake for the City’s water supply. In 1994, environmentalists and members of the Six Nations set up camp on an island in the Grand River to stop the construction of the sewer and water line. The river bed is First Nations territory and the sewer line risked contaminating the water supply downstream should it fail. In 1997, the City and Six Nations reached an agreement whereby the City would bury the lines 10 to 15 feet below the river bed. The drilling method the City planned to use failed because the bedrock was too hard for the drill. In 1998, the City built a pedestrian bridge across the river. This bridge would carry the water and sewer lines above the river to the new industrial park. The project was completed in March-2000.

Municipal Affairs

In 1997, Council appointed a Big On Brant committee to develop and implement a strategic plan for the City and the surrounding area to combat Brantford’s image problem of a struggling city of closed factories requiring government handouts. In 1999, the City hired a consulting firm to rebrand the City and give it a more distinct civic identity. The logo proposed by the consultants was criticised as being unreadable and meaningless. The City organised a contest to create a new image for the City; a new logo designed by Michael Swanson, a local artist, won the contest and $5,000 in prize money. His logo is still in use today.

Citizens and business owners were dissatisfied with the services being delivered by the City. A 1995 Mayor’s task force report concluded that City Hall was dictatorial, slow to respond, and weak on follow up. A 1998 report sponsored by the federal government concurred, citing negative attitudes, weak marketing, too much red tape, and poor decision-making and coordination.

The recession of the early 1990s created challenges for City Council. Taxes rose by over eight percent in both 1990 and 1991. In 1992, City Council sought a zero-budget increase. Budgets were slashed and all services reviewed. For the first time in thirty years there was no property tax increase. Provincial downloading instituted by the provincial government of Mike Harris in 1996 put further strains on the budget but City Council managed to avoid increasing property taxes until 1998. Provincial downloading is when the provincial government transfers the cost of providing some programmes from the province, and the provincial treasury, to local governments and thus their taxpayers. The cost of these programmes delivered locally is borne solely by the municipal (local) taxpayer.

Even though merger talks between the City and the County did not materialise, the City and County agreed to a shared services agreement in 1998 for the following services: John Noble Home, ambulance, 911, child care, social housing, and the Brant County Health Unit.

T H & B Landslide

On 22-May-1986, a landslide washed out the Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo Railway line below Colborne Street, across from Garden Avenue. The Grand River Conservation Authority believed more landslides would occur and wanted the City to buy the properties in jeopardy from the property owners. The property owners balked at the price offered to them, 1986 value less seventeen percent. The City lacked the funds to stabilise the river bank and buy all the properties and the property owners wanted a better deal so even though the river bank was rapidly eroding, by 1996 few property owners sold their property to the City. Since the budget item was high and the number of affected properties was small, this situation was not a high priority for the City or the provincial government. After a few more changes were made to determine the properties’ value, most of the properties were sold to the City. By 1999, only three property owners had not sold their property. Among the businesses along this strip were Pat Alonzo’s Music Studios, GasRite gas bar, and Clubine Lumber.

New Library

In January-1992, the new downtown library was opened. The library was located in the former Woolco store on Colborne and Market Streets. The new Library came in over budget by a large amount. City Council was now faced with the question of what to do with the old Carnegie Library building. Suggestions included converting it to a courthouse, an art gallery, and municipal offices. The building was offered to the Brant Historical Society but the $1.8 million price tag was too high for the Society and the proposal was rejected. The building was mothballed.

The downtown Woolco store was purchased by the City and converted into the Public Library, replacing the Carnegie Building on George Street. The new library opened in January-1992. The building was designed by Moffat Kinoshita Associates of Toronto. The design was runner up to the new Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto in the third annual Design Efficiency Awards and won an award of excellence from the Hamilton Society of Architects. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

War Memorial

The Brant County War Memorial was finally completed when seven new statues were unveiled on 12-September-1992. The Brant County War Memorial Committee raised $350,000 to finish the memorial. The memorial was designed by Walter S. Allward and constructed in 1933. The memorial did not include a group of statues representing Humanity because of financial constraints. Allward’s statues were of a wounded youth, a resolute mother, a figure praying, and a piece of crippled field artillery. Allward designed the Bell Memorial on West Street and the Vimy Ridge Memorial in France. On 2-July-1954, a memorial gallery designed by local architect Charles Brooks was unveiled commemorating those who perished in the Second World War. The Canadian Military Heritage Museum on Greenwich Street opened in 1993 by a group of veterans and military enthusiasts. The museum featured exhibits of wartime weapons, equipment, and memorabilia. The museum covers the military heritage of the United Empire Loyalists of the 1700s to the peacekeepers of today.

The Brant County War Memorial was finally completed when seven statues were unveiled on 12-September-1992. The statues represent the men and women who fought in the Army, Navy, and Air Force. The additional female statue represents the Medical Corp. (photo by the author)

Sunday Shopping

The issue to allow Sunday shopping was defeated in a civic referendum in 1988 however Sunday shopping became widespread after June 1990 when the Supreme Court of Ontario ruled that the Retail Business Holidays Act was unconstitutional. The Ontario Court of Appeals reversed this decision in March 1991. In June 1992, the Retail Business Holidays Act was amended to permit Sunday shopping.

No Smoking By-law

A 1988 survey indicated that thirty percent of Brantford’s residents smoked tobacco products; the highest rate in Canada. In 1998, the City tried to limit smoking in public places but was met with opposition from local businesses and the Chamber of Commerce, fearing a loss of business. A by-law to ban smoking in public places including bingo halls, bowling alleys, and restaurants was finally enacted in 2003.

Stan’s Fries on Darling Street behind the TD Canada Trust building, before the Transit Terminal was built. (photo from Pinterest)

Business Developments

The chip wagons, a downtown Brantford institution, came under attack in 1997 when downtown restaurants objected to the chips wagons as unfair competition. The matter was resolved when the wagons were charged an annual licence fee.

Tim Hortons opened the city’s first doughnut shop in 1968. By 1997, there were 25 doughnut shops operating in the Brantford. Today Tim Hortons operates 20 restaurants in Brantford.

Bingos

Bingo was a popular pastime in the City. Bingos provided a stable source of revenue for charities and minor sports organisations. The two largest bingo halls were the Delta Bingo Parlour and the Brantford Charities Bingo Palace. The Brantford Charities Bingo Palace opened in 1994. The Bingo Palace distributed almost $4.5 million to local charities in the six years it operated. The Bingo Palace closed in early 2000 as a result of the opening of the Brantford Charity Casino on Icomm Drive. Both bingo halls were under investigation for running unlicensed bingo games and for infractions of the province’s gaming rules.

In November 1992, the first telephone factory building in Canada on Wharf Street was demolished. The factory was started by James Cowherd in 1879 and operated until Cowherd’s death in 1881. This occurred even though the building once had a plaque on it noting its significance. This demolition resulted in the City compiling an inventory of heritage buildings.

Queen Elizabeth II visited Brantford in 1997 to unveil a plaque which officially designated the Bell Homestead as a National Historic Site. In 1953, a cairn and plaque placed at the Bell Homestead only commemorated the invention of the telephone and did not designate the site.

Brantford Coat of Arms

Brantford Flag and Coat of Arms

Brantford adopted its corporate seal in 1850. In 1977, it registered its first coat of arms which was presented to the City by the Zonta Club. The coat of arms was based on the 1850 corporate seal with some modifications. In 1989, the Kiwanis Club helped the City petition the Canadian Heraldic Authority for a grant of arms. The arms were officially granted on 6-March-1991. In April 1991, the City requested that a new flag be presented with the new arms. On 24-September-1991, Governor-General Ray Hnatyshyn presented Brantford’s new coat of arms and flag.

Brantford flag

Environmental Clean-ups

The City launched their blue-box recycling programme in November 1989. The programme was an overwhelming success as two tons more per day was being collected than expected.

Environmental contamination became a growing concern for the City at brownfield sites and decaying factories. As factory buildings grew older and Ontario started shifting away from its industrial economy, company owners found it cheaper to walk away from their contaminated factories rather than clean up the environmental damage.

Northern Globe on Pearl and Sydenham Streets in the North Ward was a particularly dirty site the City ultimately paid to clean up. The site manufactured roofing products since 1906, first as the Brantford Roofing Company and then Domtar when the Montreal company bought the facility in 1954. Globe Building Materials bought the plant in 1991 and renamed it Northern Globe. They closed the facility in November 1995 when Northern Globe went bankrupt. Fires in 1997, 1999, and 2001 destroyed the buildings on the property. The City took over this property in 2004. It was remediated and a soil cap was installed in 2016.

Brantford launched a brownfield programme to monitor 16 former factory sites. Brantford was an early adopter of this brownfield approach. Issues surrounding liability, ownership of the properties, and funding hampered efforts to begin remediation efforts. The Greenwich-Mohawk properties which once housed the Sternson, Cockshutt, and Massey-Ferguson factories were the first sites targeted. Remediation of these properties was only completed at the end of 2017.

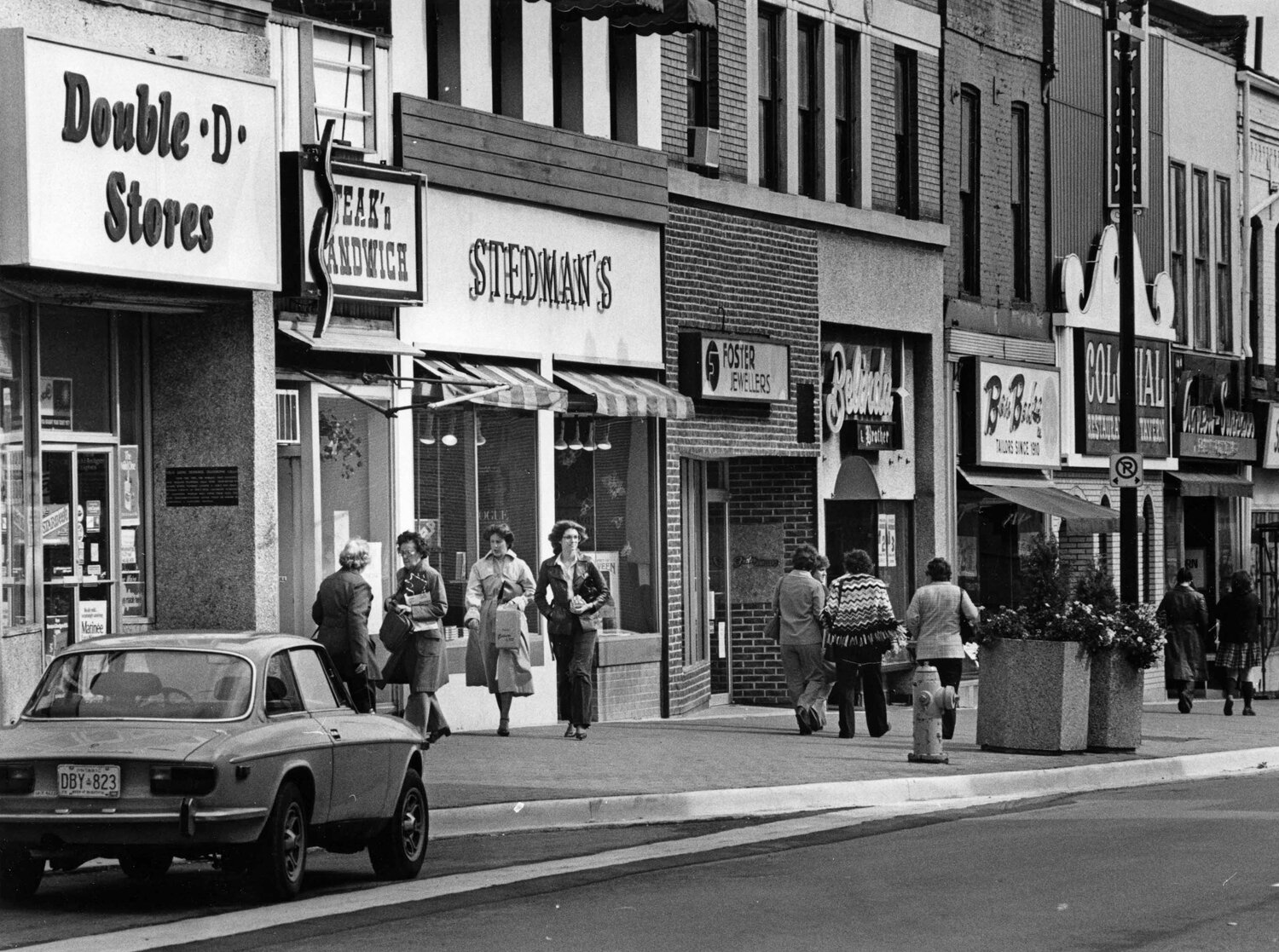

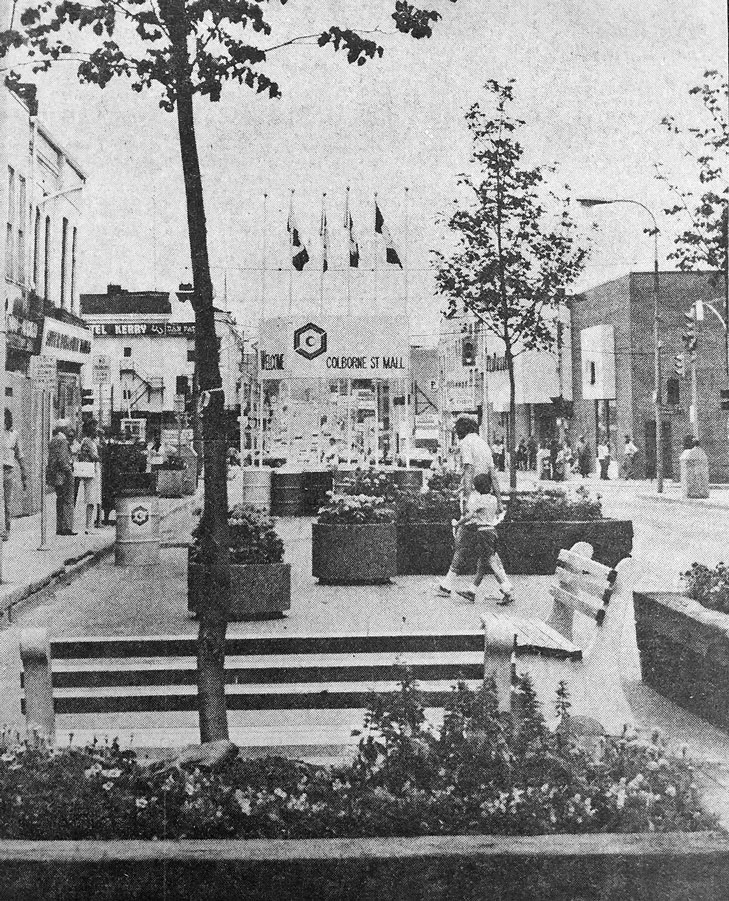

Downtown

What was supposed to be the saviour of downtown Brantford and bring people flocking back to downtown was a total flop. Eaton Market Square Mall never ended up making downtown a shopping destination. The City was ever hopeful but the downtown buildings were old, tired and in decay, especially along Colborne Street. New residents and young people were scared to go downtown because it was so rundown. The City never committed to enforcing its property standards bylaws downtown believing that working with downtown property owners would produce better results; it did not. Most owners ignored the work orders filed against their properties knowing the City was not going to take them to court. Parking was also an issue. The City removed street parking spaces in the 1970s when they tried to beautify the downtown with wider sidewalks and trees and planters. Aggressive parking enforcement also drove patrons away.

The downtown continued to eat up City resources. Staff reports, consultant reports, citizen committees, and rehabilitation funding were all used to find a solution to get citizens to return downtown. The City could not get private sector investment committed to the core, and the downtown continued to deteriorate. Some common recommendations were a return to two-way streets and to focus on encouraging housing and employment. A list of downtown initiatives included:

Colborne Street Revitalisation Association

Police Foot Patrol – 1989

Citizen’s Task Force – June 1990

Citizens’ Committee on Core Area Revitalisation

BIA commissioned study – July 1993

Mayor’s downtown task force – 1994

Operation Facelift - 1998

Consultant report to promote the municipality’s image

In July 1990, the Liberal provincial government announced that the Ministry of Government Services would move its head office to downtown Brantford. 280 jobs would move to Brantford. The Liberal government of David Pearson started to move some ministry offices out of Toronto and into smaller cities in Ontario; the Ministry of Health moved to Kingston, the Ontario Lottery Corporation head office to Sault Ste. Marie, and the OSAP programme administration to Thunder Bay. The Constellation Hotel chain showed interest in building a hotel on the Patterson candy factory property but abandoned those plans in October of 1990. The City selected this site for the Ministry of Government Services building even though a downtown task force had recommended building on the south side of Colborne Street. In April 1993, the NDP government rescinded the plan to move the Ministry of Government Services to Brantford. The announcement even caught local NDP MPP Brad Ward by surprise. Finally, the Royal Bank of Canada purchased the property in 1996 and opened a financial services centre which consolidated three bank branches; Mount Pleasant Street, Brant Avenue and Bedford Street, and the downtown branch at Market and Dalhousie Streets; into one. The new RBC office opened in 1997.

The City received a $20 million compensation package from the provincial government because of the cancelled relocation. Some of the money was used to build the Brantford District Labour Centre on Icomm Drive and some was used to set up a research centre for the recycling of plastics. The research centre had trouble attracting companies to become involved and closed in 1995 before operations even began.

The Public Utilities Commission purchased the 18,000 square foot Canadian Order of Foresters building at Market and Wellington Streets for $834,000.

Empire Company, the owner of Sobey’s supermarkets, purchased the old Koehring-Waterous site, on Market Street South, in March 1994. Their plan was to build a 60,000 square foot Sobey’s store and plaza on the site. Sobey's eventually built their store in West Brant and opened a Price Chopper at this site.

J.H. Young & Sons, jeweller, closed their downtown store in the Eaton Market Square on 30-July-1994. Young’s had been downtown since they opened in 1900. Their Lynden Park Mall store remained open.

The old Hurley Printing building at 179 Dalhousie Street, that operated at that location from 1912 to 1977, was demolished in July-1994.

Parking meters were removed from the downtown in 1994 as part of a 14-month trial. They have never been reinstalled. (photo from Pinterest)

The Mayor’s downtown task force in 1994 recommended the removal of parking meters among other things. 218 parking meters were removed for a fourteen-month trial. Parking meters were seen as a barrier to visiting downtown. The meters were never reinstalled as downtown merchants made it clear they did not want them.

In December 1994, J.P. Baron, apparently of Sarasota, Florida, planned a redevelopment of the downtown. He claimed to be backed by Saudi investors. His development would be completed over a five to eight-year period and be based around a Roaring 20s theme. He backed out citing intense media scrutiny. In turned out that J.P. Baron, also known as Paul Plishewsky, was from Cambridge, Ontario, not Sarasota. He had for a short time an office in Kitchener. In 1996 he was charged with welfare fraud.

In 1995, Waterford businessman John Stam proposed to restore a block of Colborne Street (115 to 141 Colborne Street) into a Native Heritage Arts area hosting craft and antiques stores, a tea room and a sidewalk café. Stam estimated it would cost $200,000 to purchase and renovate each of the 12 properties. His proposal attracted little interest.

John Stam’s conception of a sidewalk café at 129 Colborne Street, formerly Arn Black’s and Annie’s. (photo from the archives at the Brantford Public Library)

The tenth anniversary of Eaton Market Square in 1996 was not a celebratory one. The mall’s occupancy rate was only seventy percent and Eaton’s future was uncertain. In 1997, Eaton’s filed for bankruptcy protection. The Brantford store was one of the first to close. The Shopper’s Drug Mart store seeing no future for the mall left shortly after. As the mall’s occupancy rate continued to decline, the mall closed its lower level in 1998. A federal study conducted at the time concluded that moving Mohawk College and the YM/YWCA to the mall location would be an economic boost for the downtown.

A proposal to build a $25 million YM/YWCA including apartments and condominiums on the south side of Colborne Street stalled when the YM/YWCA decided it wanted to build on its own, but rising costs put the project out of reach.

Operation Facelift was Mayor Friel’s idea to spruce up the downtown. Volunteers would donate materials and time to paint the worst looking buildings on Colborne Street. Only one building, Lawyer’s Hall, 76 Colborne Street, was completed when funding for the campaign ended.

Two call centres opened in the mall; F.C.A. International in 1998 and R.M.H. Teleservices Centre in 1999. R.M.H. employed 500 workers when it opened. By 2000, R.M.H. employed over 1,000 workers. Downtown traffic increased significantly with the opening of the call centres but retail store openings never materialised.

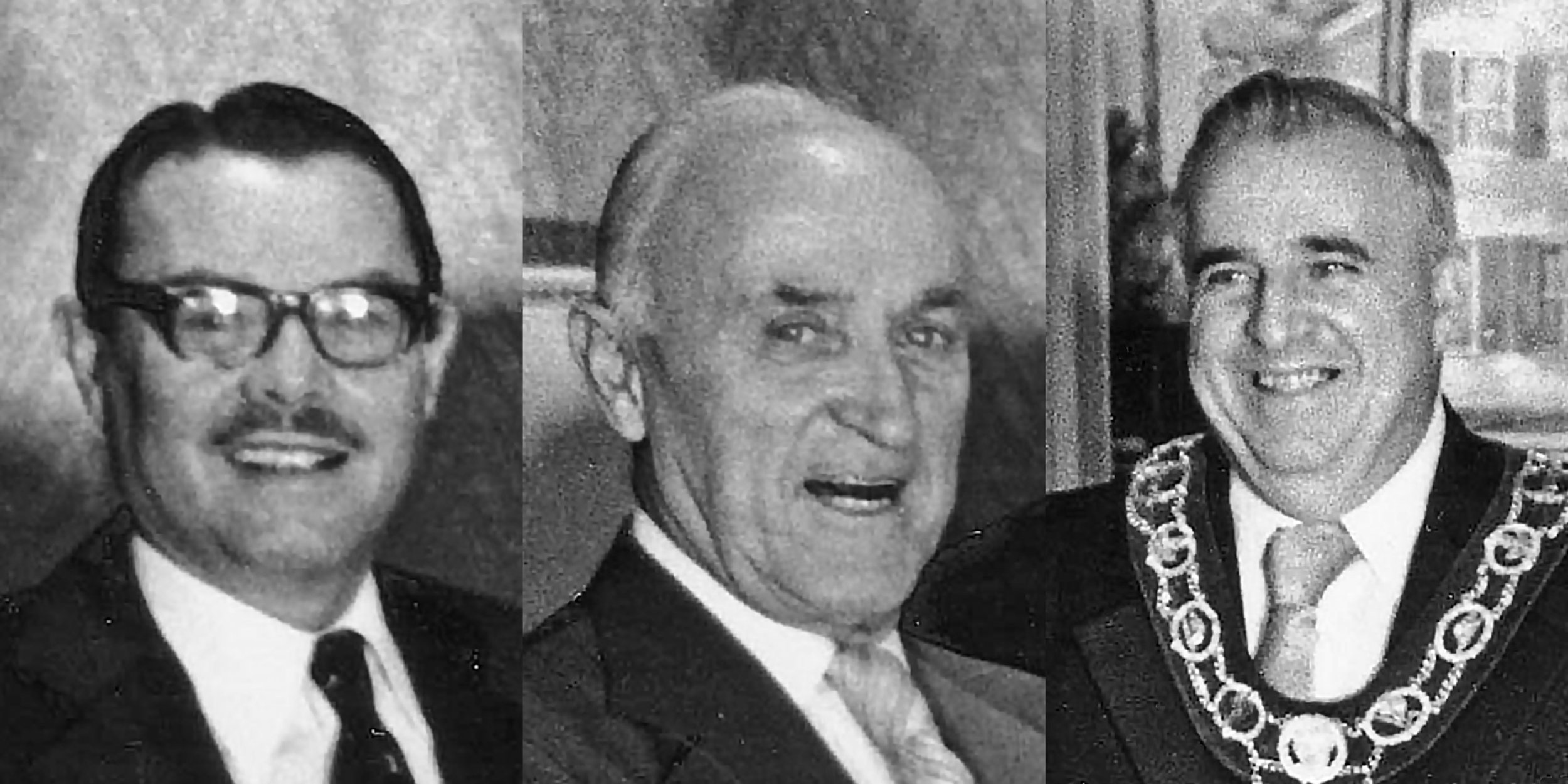

Politicians

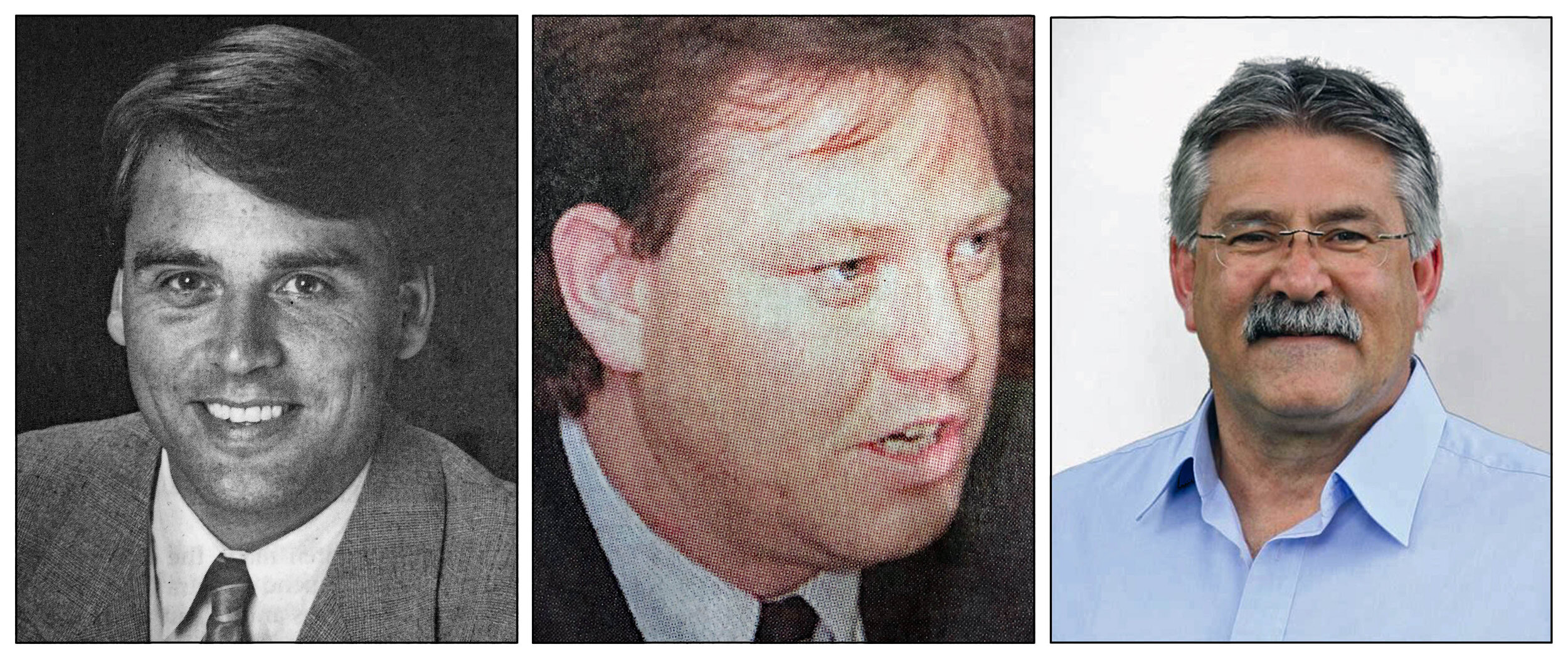

Jane Stewart, MP for Brant. First elected in 1993 and reelected in 1997 and 2000. (photo from the archives at the Brantford Public Library)

Derek Blackburn of the NDP had represented Brant in the House of Commons for 22 years when he resigned his seat in 1993. Jane Stewart of the Liberal party was elected to represent Brant in the subsequent election. Stewart won with 51 percent of the votes. Stewart won the next two elections in 1997 and 2000 with an even higher percentage of the votes. Stewart served as Minister of National Revenue from 1996 to 1997, Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development from 1997 to 1999, and Minister of Human Resources Development from 1999 to 2003. Stewart retired from politics on 13-February-2004.

Former Brantford Mayor, David Neuman of the Liberal party, represented Brantford provincially until the 1990 provincial election when he was defeated by Brad Ward of the NDP in a surprising sweep to power for the Bob Rae led party. Ward was a parliamentary assistant to the Minister of Skills Development from 1990 to 1991, a parliamentary assistant to the Minister of Industry, Trade, and Technology from 1991 to 1993, and a Minister without Portfolio in the Ministry of Finance from 1993 to 1995. In May of 1993, the Ontario government cancelled their plan to move the computer and telecommunications division of the Ministry of Government Services from Toronto to Brantford. This Ministry was planning to build a building at the corner of Brant Avenue and Colborne Street, now the site of the RBC bank branch. In the 1995 provincial election, Ward was defeated by Progressive Conservative candidate Ron Johnson. Johnson was noted as having one of the worst attendance records in the Ontario legislature and as a result was dropped from all legislative committees in 1997. Not surprisingly, Johnson did not run for re-election in 1999. Dave Levac of the Liberal party won the 1999 election narrowly defeating Alayne Sokoloski of the Progressive Conservative party. Levac was a teacher and principal before he entered the legislature. Levac was named OECTA Distinguished Teacher in 1994 for this work in conflict resolutions programmes, and citizen of the year in 1997 by readers of the Brantford Expositor.

Brad Ward, MPP for Brantford. He served one term from 1990 until 1995.

Ron Johnson, MPP for Brantford. He served one term from 1995 until 1999.

Dave Levac, MPP for Brant. Levac served from 1999 to 2018. He was the longest serving Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, from 2011 until 2018. (photos from the archives at the Brantford Public Library)

Municipally, Brantford entered the decade with Karen George as Mayor. George was defeated in the 1991 election by Bob Taylor. In 1994, Taylor was defeated by 27-year-old Chris Friel. Friel won re-election in 1997 and 2000. Friel is noted for declaring that Brantford had the worst downtown in Canada in a Toronto Star article published on 19-May-1994. The Star published a follow up article “Brantford fights back” on 8-Nov-1999. Friel was opposed to establishing a casino in Brantford. He felt a casino diverted money from the municipality to the province. The Brantford Charity Casino opened in November-1999. Friel worked to establish a campus of Wilfrid Laurier University, known colloquially as Laurier Brantford, in downtown Brantford. The campus opened in 1999. Friel wanted to begin merger discussions with Brant County in 1996, but the county was not interested and instead reorganised itself into a single municipality in 1999.

Bob Taylor served as Mayor from 1992 until 1994.

Chris Friel was elected Mayor in 1994 and again in 1997 and 2000. He was defeated in the 2003 and 2006 elections but reelected in 2010 and 2014. (photos from the archives at the Brantford Public Library)

In 1995, after lengthy and intense discussions Brantford City Council replaced the use of the term Alderman with Councillor. Max Sherman retired from municipal politics in 1997 after 31 years of service.

Police and Fire

In January 1991, the Brantford Police Department changed its name to Brantford Police Services. In November 1991, the police department moved into its new headquarters at Wayne Gretzky Parkway and Elgin Street leaving its antiquated 1950s headquarters at Greenwich and Newport Streets behind.

Police Chief Al Barber succeeded John Weir in 1987. Barber retired in 1998 and was succeeded by Bob Peeling. Barber led a significant change in the force’s approach to policing. Barber wanted closer ties between the department and the public. Community policing was implemented where the same police officers were stationed in particular areas of the city so they would become a familiar presence in their assigned neighbourhoods. First the downtown was addressed, then the north end. In 1992, the concept was rolled out city wide. In 1994, the police service announced an effort to include more women, Aboriginals, minorities, and the disabled to its ranks.

The province restructured police services in 1996 and it appeared that the city police force would amalgamate with the police services in Paris and Brant County, but Brant County rejected this proposal.

Crime rate statistics from 1999 showed the crime rate fell by fifty percent since 1983. However, drug offences, youth crime, use of weapons, and crimes of violence were increasing. Eleven murders and 541 robberies were committed in the City in the 1990s.

On 3-March-1992, it was discovered that two machine guns, 64 C7 rifles, and 9 Browning 9mm semi-automatic pistols were stolen from the Armoury, the largest robbery of an armoury still to this day. A man was charged and most of the weapons were recovered. The machine guns were WWII vintage and had no firing pins, 45 rifles had missing bolts and the 9mm pistols did not have barrels. The bolts and the barrels were stored separately. No ammunition was taken. It turned out that the burglar alarm at the armoury was not connected to the new police station, it remained connected to the old empty police station, so the police were not aware that the alarm was triggered when the robbery occurred.

The police had to deal with the shaving cream attacker, a man who would sneak up on women and smear their face and hair with shaving cream. After nine months the attacker was caught; the attacker apparently suffered from impulse control disorder.

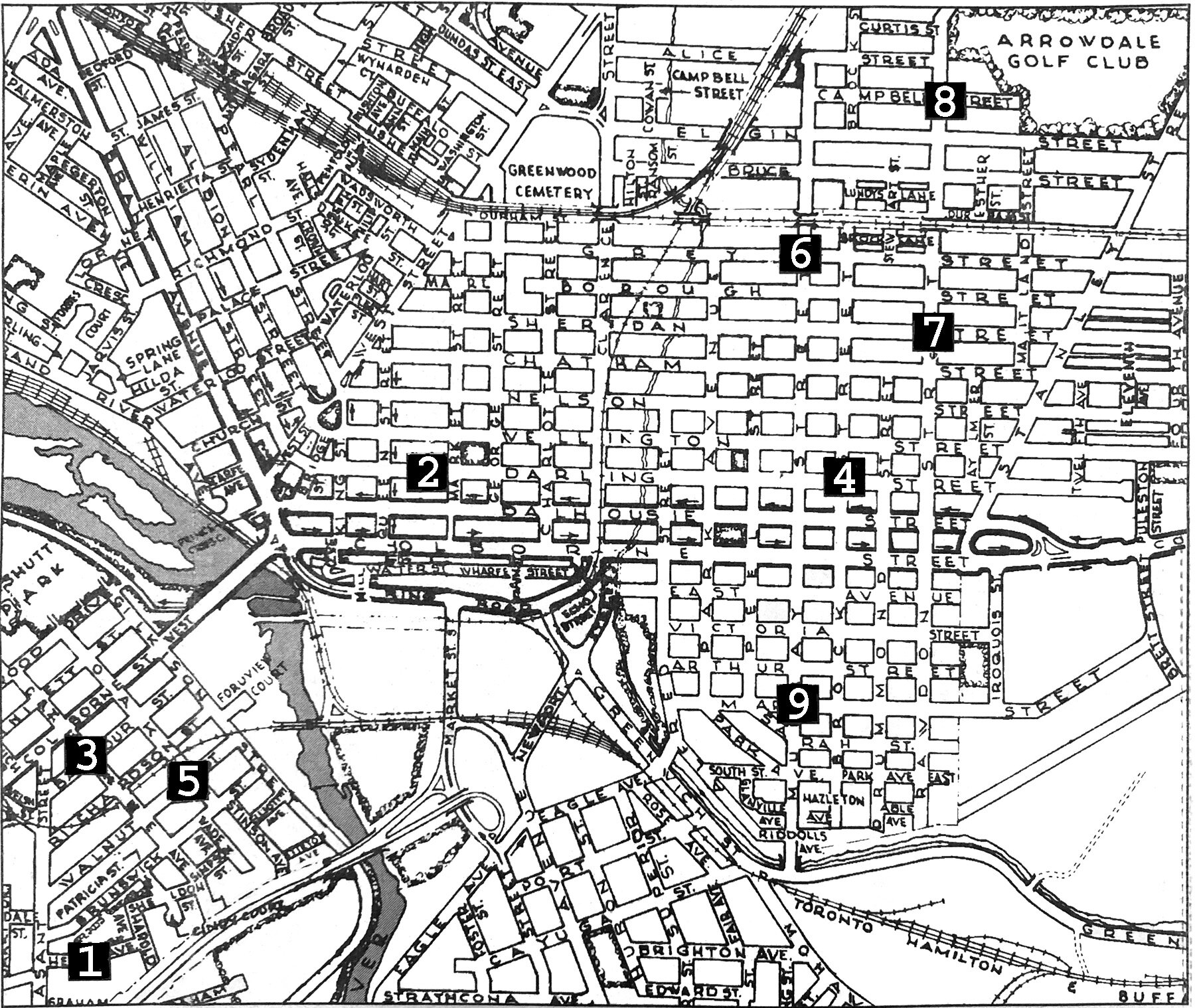

The Shaving Cream Attacker stalked victims in East Ward and West Brant between 7-December-1993 and 7-July-1994. Nine women between the ages of 14 and 29 were attacked. Thomas Ranson, 21, admitted to seven attacks and was sentenced to 60 days in jail. The attacks occurred on 1) 7-December, 2) 24-January, 3) 15-March, 4) 19-April, 5) 13-June, 6) 15-June, 7) 17-June, 8) 28-June, and 9) 7-July. (from the archives at the Brantford Public Library)

On 9-April-1994, an American trucker, Michael Lovejoy, was found shot to death in the sleeping compartment of his cab which was parked on the shoulder of Highway 403 between Garden Avenue and the Wayne Gretzky Parkway. Lovejoy parked his rig on Friday afternoon 8-April and set his alarm to wake himself up at 5:30 pm. Another tractor-trailer was seem parked behind Lovejoy’s rig on Friday afternoon. Despite continent wide publicity and flyers distributed to all truck stops between Flint, MI, and Buffalo NY, along the Highway 402/403/QEW corrridor, no leads were uncovered. This crime remains unsolved.

Michael Lovejoy of Flint, MI, driving for RTS Transport, was found shot to death in the sleeping compartment of his rig on Saturday afternoon 9-April-1994. Lovejoy parked his rig on the shoulder of Highway 403 on Friday afternoon 8-April. His parked rig was noticed by a fellow RTS Transport driver who passed it twice on Saturday on his way to and from Buffalo. The driver stopped to investigate and found Lovejoy dead. The circumstances surrounding Lovejoy’s death remain a mystery. (from the archives at the Brantford Public Library, photo by Brian Thompson, Brantford Expositor)

The courthouse at Wellington Square was too small and crowded to accommodate all the cases brought before the court. There was also an insufficient number of judges to hear the cases and make timely judgments. In 1992, an extra half of a judge of time was added. In January 1993, the province requested proposals to find a new facility to accommodate all court facilities under one roof in downtown Brantford. The company that was awarded the tender withdrew their bid citing it was not economically viable to proceed. The project was retendered but the courthouse size was reduced by forty percent leaving it with no more space than the current facility. The City and police objected but the province moved forward undeterred. A new courthouse was constructed next to the family court building on Darling Street. It opened in 1996.

A new fire department headquarters was opened on 29-May-2000 at Clarence and Wellington Streets. No tears were shed when firefighters moved out of their problem plagued 1950s headquarters building on Greenwich Street.

The fire department was kept busy during the decade. Brant Dairy moved from Dalhousie and Stanley Streets to Elgin Street in 1992. On 7-August-1992, their vacant building was set ablaze. The old Massey-Ferguson foundry on Greenwich Street was set on fire on 7-November-1992 by two boys aged 13 and 14. The downtown building at 53 / 55 Colborne Street was set ablaze on 1-August-1993. The building was owned by Stephen Kun and housed the Appliance Repair Centre which was operated by John Bragg for 17 years. The building was repaired and the fourth floor was removed. The C.J. Mulholland Mattress Factory at 363 Colborne Street burned on 25-September-1994. The fire was thought to be deliberately set. Pauwel’s Travel, 95 Dalhousie Street experienced a second storey fire on Tuesday morning 11-October-1994.

Brant Stereo fire 3-November-1994. The fire started in the store basement. The building was built in 1880. Brant Stereo had been operating from this location since 1979 and is still in business at this location. (from the archives at the Brantford Public Library)

A fire started in the basement of Brant Stereo, 44 Market Street on Thursday morning 3-November-1994, gutting the store. The store building was built in 1880. Brant Stereo has been located there since 1979. $3.5 million of inventory, just received for Christmas was lost. Moffat Lunch and the Odeon Theatre both received smoke and water damaged.

Fire damage in 1995 was the heaviest it had been in a decade. Hill & Robinson Funeral Home, 30 Nelson Street at Queen Street, suffered a fire on 12-April-1995. The storage barns at Cashway Lumber on Park Road North burned on Sunday 14-May-1995. The empty Bay State Abrasives building at McMurray and Pearl Streets was set on fire on 6-September-1995. Five people died in a house fire at 26 1/2 West Street on 24-September-1995. Four children and their mother perished. The fire was set by one of the children. A fire started in the rear of Maich Appliances, 61 Colborne Street, on 20-October-1995. The Solaray factory in Holmedale was gutted by an arsonist on 30-October-1995. A fire at Lee-way Plumbing Supplies on Colborne street east of Murray Street on 23-December-1995 destroyed the building along with two other businesses, Copyd, and the Ontario Public School Teachers’ Federation office. This building was located across the street from St. Mary’s Church.

On 4-January-1996, a fire was set at the former House of Hagen Bakery & Delicatessen, 131 Colborne Street, downtown. On 10-January-1996 a fire was started in the Twin Eagle Variety Store located in the Temple Building on Dalhousie Street next to the former Federal Building. The fire quickly spread to the second and third floor apartments over the store but was contained by firefighters.

On Saturday 9-March-1996 an explosion destroyed a fourth floor apartment at the 6-storey Slovak Village on 5th Avenue, blowing out the wall of the apartment unit. A former tenant, Douglas Swift, angry for being evicted from the apartment building, arranged for Richard Teichmann, of Dundas, to torch the unit. Teichmann soaked the unit in gasoline and lit a match. He was blown out of the unit 300 feet away into a field. The blast caused $1.5 million damage to the apartment building and took 16 months to repair.

Damage from an explosion at the 6-storey Slovak Village apartment building on 5th Avenue on 9-March-1996. Unit 413 was doused in gasoline and ignited. Six units were destroyed in the blast. Richard Teichmann, of Dundas, was sentenced to 22 months in jail for setting the blast. Douglas Swift, the unit’s former tenant, was charged with conspiracy to commit arson. Swift was angry by his eviction from his unit a few months earlier. The blast caused $1.5 million damage to the apartment building and took 16 months to repair. (from the archives at the Brantford Public Library, photo by Wayne Roper, Brantford Expositor)

On 20-December-1996 a fire was started in the lost and found bin at St. Theresa School on Dalewood Drive. The fire occurred on the last day of school before the Christmas break. 350 students had to be evacuated.

A tire fire broke out at Otterwood Tire Recycling and Storage on 2-December-1997. The facility was located in the old Sternson Factory on Mohawk Street. The site contained 40,000 tires. 7,000 tires burned. Arson was the cause. The abandoned Northern Globe roofing factory on Pearl Street was twice set ablaze by arsonists; in 1997 and 1999.

A fire at Searle Manufacturing, 122 Copernicus Crescent on Monday 19-April-1999 marked the Fire Department’s first use of their heat sensing camera to locate hot spots and fight the fire.

The Hagersville Tire Fire started on Monday 12-February-1990. 14 million tires were stored on a 14-acre site operated by Tyre King Tyre Recycling, and owned by Ed Straza. The fire was fought by volunteer firefighters from 10 municipalities. High winds and poor weather hampered their efforts, grounding water bombers for days. Freezing rain produced extremely hot steam and fog. The fire took 17 days to put out. A gang of five area boys were found responsible for setting the fire. (from the archives at the Brantford Public Library)

Education

In 1990, the Brant County Board of Education made a major investment in technology by installing a keyboard conferencing system, desk-top publishing, and one computer in every classroom. French immersion was under threat as the school board looked to reduce costs by reducing its scope. The introduction of junior kindergarten was contentious because of the money needed to run the programme.

Students with academic challenges in grade school were identified and directed to vocational programmes at Herman Fawcett. Changes made by the Ministry of Education led to destreaming and consequently, Herman Fawcett Secondary School needed to make changes to its programmes in order to accommodate a wider range of students. These changes led to the renaming of the school in 1995 to Tollgate Technological Skills Centre.

Thomas B. Costain elementary school closed in 1998, after 45 years of service to its neighbourhood. Half-day child care was launched at Pauline Johnson Collegiate in 1988. The programme was expanded and a preschool programme was introduced in 1995 with the opening of a new building next to the high school. A day-care centre for Herman Fawcett Secondary School was rejected by City Council in 1992. These day-care centres were designed to keep teenage mothers in school. The province stepped in to provide funding. The Brant Community Development Agency then agreed to fund and operate the day-care. The day-care continued to operate until the demise of the Brant Community Development Agency. The public school board also initiated the Learning, Earning, and Parenting programme in 1999. This programme allowed teenage mothers on welfare to attend school. The Lansdowne Children’s Centre which provided day-care for over 1,000 disabled children and young adults got a new facility. The centre began in 1952. In 1998, the new facility opened at the former Jane Laycock School on Mount Pleasant Street. It was funded by provincial money and community donations.

Pauline Johnson Collegiate Child Care Centre. This $450,000 building opened in 1995 replacing a former windowless tech classroom. The centre was built under the direction of its first director, Geke Nolden, to provide a bright, airy environment for the children. The day care accommodates 10 infants, 10 toddlers, and 24 pre-school children. The centre is now known as the Brantford Little School Community Child Care Centre and is open to all children. (photo by the author)

Constable Bill Doherty, high school resource officer. St John’s College became the first school in Ontario to hire a police resource office, to create a better rapport between students and the police and to help students understand the role of a police officer in the community. (photo from the Brantford Police 1990 Annual Report)

Enrolment at the Catholic School Board continued to increase. 1990 witnessed the largest increase in its history requiring the hiring of 27 teachers and the addition of eight portables . To alleviate overcrowding at the secondary school level, Assumption College School opened in the fall of 1992. St John’s College became the first school in Ontario to hire a police resource officer, Constable Bill Doherty, to create a better rapport between students and the police and to help students understand the role of a police officer in the community. Chief Bob Peeling led this initiative. When Assumption College School opened in 1992 the police resource officer divided their time between the two schools. This programme was expanded to North Park, Pauline Johnson, and Tollgate Tech in September 1990, and to BCI in September 2000.

Assumption College School opened in 1992 to ease the overcrowding at St John’s College. Brantford’s second Catholic High School since the merger of St John’s and Providence College. An addition was completed in 2007. (photo by the author)

The Strap. Strapping, generally applied to the hand, was a form of corporal punishment, used to discipline children. The strap was made of leather or a rubber belt wrapped in canvas. Strapping was banned in public schools in 1992. The separate school board banned the strap in 1987. The use of the strap in Canadian schools was outlawed by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2004.

The use of the strap was banned in public schools in 1992. The separate school board banned the strap in 1987.

Funding cuts to education made by the Bob Rae NDP government in 1993 and further cuts made by the Mike Harris Progressive Conservative government led to teacher unrest. Teachers began to work to rule and withdrew services such as coaching sports teams and after-hours homework help. In 1993, the county’s public high school teachers were the second lowest paid in the province so they launched a two-month work to rule campaign in protest. In 1997, separate school board teachers went on strike, the board’s first ever teacher strike. Later in 1997, teachers from both boards joined a province-wide strike to protest government cutbacks and education policies. In 1998 public secondary school teachers worked to rule for four months while negotiating a new contract.

James Hillier, born in Brantford in 1915, was a graduate of Brantford Collegiate Institute and the University of Toronto. Hillier and colleague Albert Prebus built the first North American electron microscope at the University of Toronto in 1938. He joined the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) in Camden, NJ in 1941. Hillier rose through the ranks at RCA and when he retired he was the Executive Vice President and Chief Scientist of RCA Labs. Hillier remained involved with the Brantford community and established the James Hillier Foundation in 1993 to award annual scholarships to Brant County students pursuing an education in Science. Hillier is buried in the Farringdon Cemetery.

Dr. James Hillier, the co-inventor of the electron scanning microscope, offered to match locally raised money to establish a scholarship in his name for science students intending to attend university. A $1.2 million scholarship was established in 1996.

The passing of the province’s Fewer School Boards Act in 1997 resulted in the amalgamation of the Brant County Board of Education, Norfolk Board of Education, and the Haldimand Board of Education into the Grand Erie District School Board on 1-January-1998. The Catholic Boards in the three counties were amalgamated into the Brant Haldimand Norfolk Catholic District School Board.

Enrolment at Mohawk College was exploding at this time. Enrolment jumped by 20 percent from 1989 to 1990. Desks and classrooms were in short supply; the school implemented a shift system to accommodate the students. The college invested in a campus expansion in the early 1990s that saw the school change from a satellite campus to a full-service campus. Continuing budget constraints affected the number of programmes the campus could offer. In 1996, the school planned to build a third building, but the provincial government implemented a freeze on capital spending. The school then opted to discontinue its nursing programme in Brantford, a programme that was transferred from the Brantford General Hospital in 1973. The College looked to move into the Eaton’s Market Square building or the icomm building as an alternative to expanding its campus. The move had the backing of the provincial government since the College would be leasing the buildings rather than owning them but a move never materialised.

In the 1990s, Brantford was the largest city in the province without a university. A committee of the Brant Community Futures Development Corporation, later known as the Grand Valley Education Society planned to open a private liberal arts university in the city, to be named the University College of the Grand Valley. Coincident with this plan Wilfrid Laurier University was considering Brantford for a satellite campus and approached the Grand Valley Education Society. Laurier was interested in the icomm building, but it had just been sold for a casino. Laurier also expressed interest in establishing a campus in the Victoria Park area. In May 1998, the City offered Laurier the renovated and vacant Carnegie Library building. On 30-June-1998, the City and Laurier agreed to operate a temporary campus in the Carnegie building for a five-year period. In September 1999, 39 students, known as the pioneers, began their studies in the Contemporary Studies programme, a programme unique to the Brantford campus. In 2000, the City gifted the Holstein building to the university for use as a residence.

In 2000, enrolment at Mohawk was up to 725 students, Mohawk’s thirtieth year in Brantford. Laurier had an enrolment of 130 full time students in 2000, its second year of operation in Brantford.

P.U.C.

The Public Utilities Commission (P.U.C.) was responsible for Brantford’s water works, electricity distribution, and the buses. It was formed in 1935 by the amalgamation of the Hydro Electric Commission, the Board of Water Commissioners, and the Municipal Railway Commission. As the decade progressed, disagreements and tensions developed between the P.U.C. board and the City over the cost of running a second elected body to manage water, electricity, and the buses. The City hoped to save $1 million a year by eliminating the P.U.C. and taking the services in house, except for electricity, which would be set up as a separate City-owned company, as per provincial regulations. A separate P.U.C. was seen by many critics to be an antiquated form of managing these services. The dismantling of the P.U.C. began in 1996 and was completed on 30-August-1998 when the P.U.C. was dissolved and its elected board was replaced by a City appointed board.

PUC Building. This mid-century modern building opened in 1957. It was the headquarters of the Public Utilities Commission. Built for $395,000 by Hamill Construction of Galt (now Cambridge), Ontario. The building was remodelled and repurposed into classroom and administration space for Nipissing University in 2008. Nipissing closed their Brantford campus in 2018. (photo by the author)

In 1990, a geneticist at the University of Western Ontario (now Western University) in London advised residents not to drink the tap water because the presence of NDMA (N-Nitrosodiamethylamine) made Brantford water unsafe to drink. The main source of the contamination was from the Uniroyal Chemical plant in Elmira. This led civic leaders to question the ability of the PUC to provide clean, dependable water services. In 1996, a new water treatment system was introduced to eliminate the foul taste of the drinking water. This system also reduced the amount of chlorine that needed to be used. The foul taste was not related to the Uniroyal contamination.

Bus ridership continued to decline while losses from operating the service increased. A new bus terminal, smaller air-conditioned buses and various marketing programmes did not stabilise ridership. Consequently, fares increased and service was reduced. In 1995, the provincial government cut transit subsidies to municipalities which increased the losses suffered by the City. In 1999, Brantford Transit introduced dial-a-bus which was North America’s first curb-to-curb bus service. This service operated on weekday and Saturday evenings and all-day Sunday in place of a fixed bus route. A customer would be picked up at their door within 45 minutes of calling for a bus. The service was so successful that additional buses were added but rising losses forced the service to be cut back. It was reduced to two fixed routes and four on-demand buses. The P.U.C. operated the city transit service from 1935 until March 1997 when the municipality took over. Bus service between Brantford and Paris operated by the P.U.C. ended on 21-June-1996. Private operator About Town Transportation provided service between the two centres from 1996 until 2004.

Arts, Culture, Recreation and Sports

Interior renovations of the Sanderson Centre to restore the building to its 1919 design, which began in October 1989, continued. When the theatre reopened on 8-September-1990 the Expositor noted that it was the “most thorough restoration job in the history of Brantford”. The cost of the restoration, budgeted at $5.8 million, came in at $6.4 million. Anne Murray was the headline performer on opening night. The restoration work earned the theatre the 1991 Historic Theatre Preservation Award from the League of Historic American Theatres. The Theatre’s diverse entertainment offerings and less than ideal size has contributed to its yearly operating deficit. As a City owned facility, it has a mandate to provide a range of entertainment options even if the market for those offerings is small. Mid-size theatres in North America struggle to cover their operating costs. The City attempted to sell the theatre to private interests in 1993 but no taker could be found.

Sanderson Centre concert hall. (photo by the author)

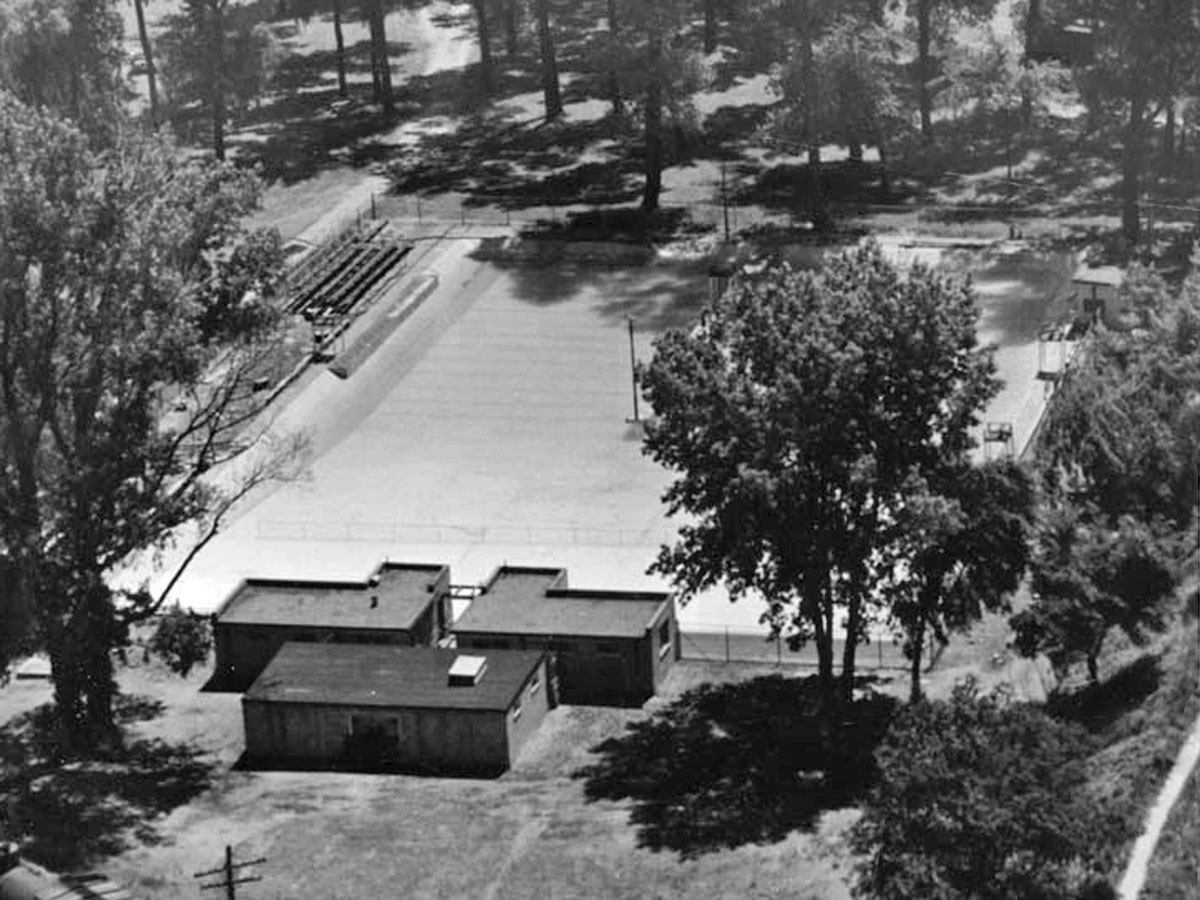

In 1994, the City received a provincial grant to study the feasibility of a clean up of Mohawk Lake. It was the seventh study conducted of the lake since 1950. The report concluded the lake wasn’t as polluted as once thought. Clean up was estimated at $3.8 million. The City was to receive $6 million from the provincial government to clean up the lake and Mohawk Park. This was part of the compensation package when the Ministry of Government Services office was cancelled. The new Harris government cancelled this funding in 1995. Mohawk Park was made fully accessible in 1994. This improvement was funded by donations from 15 local companies totalling $130,000.

An aerial view of Mohawk Lake.

Waterfront Park opened in 1989. Built by private investors it was not able to make a return on its investment and was turned over to the City in 1995 and renamed Earl Haig Family Fun Park. The image also shows the remains of the go-cart track which was decommissioned and removed.

Waterfront Park was built in 1989 by private investors to replace Earl Haig Pool. The water park never did well due to sporadic attendance and rising property taxes. In 1995, the owners of the park agreed to turn over the assets of the park to the City in exchange for a contract to manage the park for ten years. Park profits would be split with the City. In 1996, the management company decided they would no longer manage the park. The City assumed operation of the park and renamed the facility the Earl Haig Family Fun Park.

Iroquois longhouse built at Kanata Village.

The development of the trail system throughout Brantford began. The Brant Waterways Foundation, the City, the Grand River Conservation Authority, and S.C. Johnson and Son partnered to develop over 40 kilometres of trails. These trails connected to the Brantford to Hamilton trail built on the old Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo Railway roadbed, and the Brantford to Cambridge trail, built on the Lake Erie & Northern Railway roadbed. Brantford became a trail hub because of these connections to adjacent communities.

Plans to construct an authentic 17th century Iroquois village as a tourist attraction began in 1996. Kanata Village, built across from the Mohawk Chapel, opened in May of 2000. The site was successfully operated and drew visitors interested in First Nations culture and heritage. The Mohawk Workers group began an occupation of the site in 2007 and attendance declined.

In 1995, Brantford placed first in the Communities in Bloom national horticultural competition for cities with a population between 30,000 and 100,000. The City also placed first for the best planned and maintained floral arrangements. In 1996, Brantford placed first in the Nations in Bloom competition for cities with a population between 25,000 and 125,000. Brantford was the only non-British winner in the competition. In 1997, Brantford took top honours in the Class of Excellence category in the Communities in Bloom national awards competition. This category was for past winners.

Brantford hosted the 1991 Canadian Games for the Physically Disabled. The event attracted over 350 athletes and involved over 350 volunteers.

Doug Hunt set the world stilt-walking record on 23-September-1998 when he walked 54 steps on stilts measuring 50 feet, 5 inches long, without touching his safety lines. He broke his record on 14-September-2002 when he walked 29 steps on stilts 50 ft, 9 inches long. Although two men have since walked on higher stilts they were not able to walk a minimum of 25 steps which qualifies for the record. (photo courtesy of Doug Hunt)

On 23-September-1998, Doug Hunt set a world’s record for tall stilt walking and heavy stilt walking. Hunt walked 54 steps on stilts that were 50 feet, 5 inches high, weighing a combined 126 lbs. His stilts were made from carbon fibre sailboat masts bolted together. On 14-September-2002, Hunt broke his own record by walking 29 steps on stilts 50 feet, 9 inches high, weighing a combined 137 lbs.

The Zamboni Company launched an online contest to select the most popular Zamboni driver to celebrate the company’s 50th anniversary. The contest received more than one million votes and by November 1999, it was a race between two men, Octopus Al Sobotka, the Zamboni driver at Detroit’s Joe Louis Arena, and Jimmy the Iceman MacNeil, the Zamboni driver at the Brantford and District Civic Centre. Sobotka had the support of the Detroit Red Wings and their fans while MacNeil was supported by Walter Gretzky and Brantford residents. MacNeil won the contest. It included an all-expenses paid trip to the 2000 NHL All-Star game, which was held in Toronto that year. MacNeil’s father was a Zamboni repairman. The Zamboni Company opened their Brantford manufacturing facility in 1967.

Jimmy “the Iceman” MacNeil, of the Brantford ad District Civic Centre, was voted the most popular Zamboni driver in a contest run by the company to celebrate its 50th anniversary in November-1999. MacNeil beat out “Octopus Al Sobotka, the Zamboni driver at Detroit’s Joe Louis Arena.

Brantford Smoke logos from 1991, 1992, and 1996.

Professional hockey returned to Brantford in 1991 when the Brantford Smoke began play in the new Colonial Hockey League. This was the City’s first professional hockey team since 1910. The team won the Colonial Cup in the 1992-93 season over the St. Thomas Wildcats. The team was successful on the ice but not at the box office. The team was sold to American owners in 1997 and despite pledging to keep the team in Brantford, they moved the team to Asheville, NC for the 1998-99 season.

The Wayne Gretzky Celebrity Tennis Classic began in 1981. It was a fund-raising event to support the Canadian National Institute for the Blind. The tennis tournament changed to a celebrity softball tournament at the close of the 1980s. The softball tournament ended in 1992. The tournaments raised $1.2 million for the CNIB over its twelve-year run. In 1994, the City held a banquet for Gretzky and his family at the Civic Centre in recognition of Gretzky breaking the NHL record for most goals scored, long held by Gordie Howe. Gretzky retired from the National Hockey League in 1999, after playing for 20 years. Wayne Gretzky holds or shares 61 records listed in the NHL’s Record Book: 40 for the regular season, 15 for the Stanley Cup playoff and six for the All-Star Game.

Kevin Sullivan set the world record for the 800 metres at the Ontario junior track and field championships in 1992. In 1993, Sullivan became only the fifth North American high schooler to run the mile in under four minutes.

Kevin Sullivan, a runner, set the world record for the 800 metres at the Ontario junior track and field championships in 1992. In 1993, Sullivan became only the fifth North American high schooler to run the mile in under four minutes. Sullivan won a silver medal at the 1994 Commonwealth Games in Victoria, BC, in the 1,500 metres and represented Canada at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, Australia. Swimmer Julie Howard competed for Canada at the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona, Spain, and the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, GA.

Rhapsody on Ice, the Brantford-based, female precision skating team folded after their final performance in Denmark in December-1992. In the summer of 1985 Neil Young, Wayne Francis, and Marjorie Black, together with choreographers Scott Kufske, Carol Forrest and Dave Campbell began to build a team to tour the world.

Health Care

Balancing the hospital budget has been a perpetually trying task. Between December 1990 and June 1991 the Brantford General Hospital closed two wards resulting in the loss of 78 beds because of budget deficits, reducing the bed count to 303 beds. Forty years previous, the hospital had 550 beds. Another budget deficit in 1996 resulted in the loss of 65 beds, 106 full time jobs, and 23 chronic care beds which were moved to St. Joseph’s Hospital. St. Joseph’s also reduced staff from 315 to 285 between 1991 and 1996.

Continuing cuts to hospital funding from the province required a review of the two hospitals and how best to provide cost efficient services. A 1995 report by the Hospital System Planning Task Force recommended closing 81 beds, cutting 100 jobs, and making the Brantford General Hospital the sole provider of acute care and St. Joseph’s the sole provider of chronic care. The recommendation was not received well by St. Joseph’s Hospital as it had just opened four renovated operating rooms, a day surgery and an outpatient area. On 27-November-1997, the Ontario Health Services Restructuring Commission ordered St. Joseph’s Hospital to close by April 2000 to become a nursing home. BGH would receive funding to undergo a major renovation. St. Joseph’s looked to partner with McMaster University Faculty of Health and become the county’s chronic, rehabilitative, and palliative care treatment centre but this appeal was rejected by the province. St. Joseph’s closed in June-2001, an extension from the original date in order to give the BGH time to finish their renovations.

The BGH renovations was budgeted at $57 million. An $11 million fund-raising campaign for the hospital was launched. In 1996, an oncology clinic and kidney dialysis centre opened at the BGH. BGH also installed the world’s first X-ray camera that could take multiple images without moving the patient.

The aging John Noble Home required extensive upgrades and modernisation. Converting St. Joseph’s Hospital to a long-term care facility would ensure a supply of beds for the community until renovations could be made at the John Noble Home. 205 beds were transferred from the John Noble Home to the converted hospital.

In April 2000, the City and County agreed to come together and operate the ambulance service as a County department.

Icomm

The interactive communications complex, named icomm in 1990, saw its cost projections go up while attendance projections went down. The complex was caught between the building boom of the late 1980s and the recession of the early 1990s. The cost of the facility had risen to $23 million in February 1990 from $15 million a year earlier. Predictions of 700,000 annual visitors was revised down to 450,000. The complex was planning a July 1991 opening but this was pushed back to the spring of 1992 so all of the exhibits could be completed. The local fundraising campaign to raise $3 million was going poorly. By April 1991, the price for the complex was now at $29 million which meant that $6.6 million was required from the provincial and federal governments to keep the project going. An audit of the books did not reveal any fraudulent activity but it did reveal poor project and cost management. The City and some corporate backers provided money to complete the building which opened to the public, empty of displays and content, in October 1991. Over 5,000 people attended the open house. Project costs continued to climb to $31.4 million in 1992 while attendance figures were again reduced to 225,000, and the opening was pushed back to the fall of 1993, then later revised to sometime in 1994. The provincial and federal governments contributed $3.6 million to the project in 1992 to stabilise the operation. An $8 million national fund-raising campaign aimed at the telecommunications industry in Canada was launched in May 1992. This campaign was not successful as businesses in Canada were dealing with the effects of the recession.

In 1992, City Council changed the name of the street to icomm Drive from The Ring Road in anticipation of the museum’s opening. By February 1993, $3 million was still needed to complete the exhibits and a secret report prepared for the museum president recommended that the project be shut down. On 2-March-1993, the Expositor reported that icomm had been cancelled. $20 million of public and private money had been invested in the project. The City assumed the building on 30-March-1993. A scaled down version of the museum was proposed by a group of citizens but there was too much uncertainty in their proposal. City Council decided to mothball the facility in September 1993. A number of possible uses for the building were contemplated including: a museum, arts studio, Mohawk College campus, business incubator, research centre, hotel, and casino.

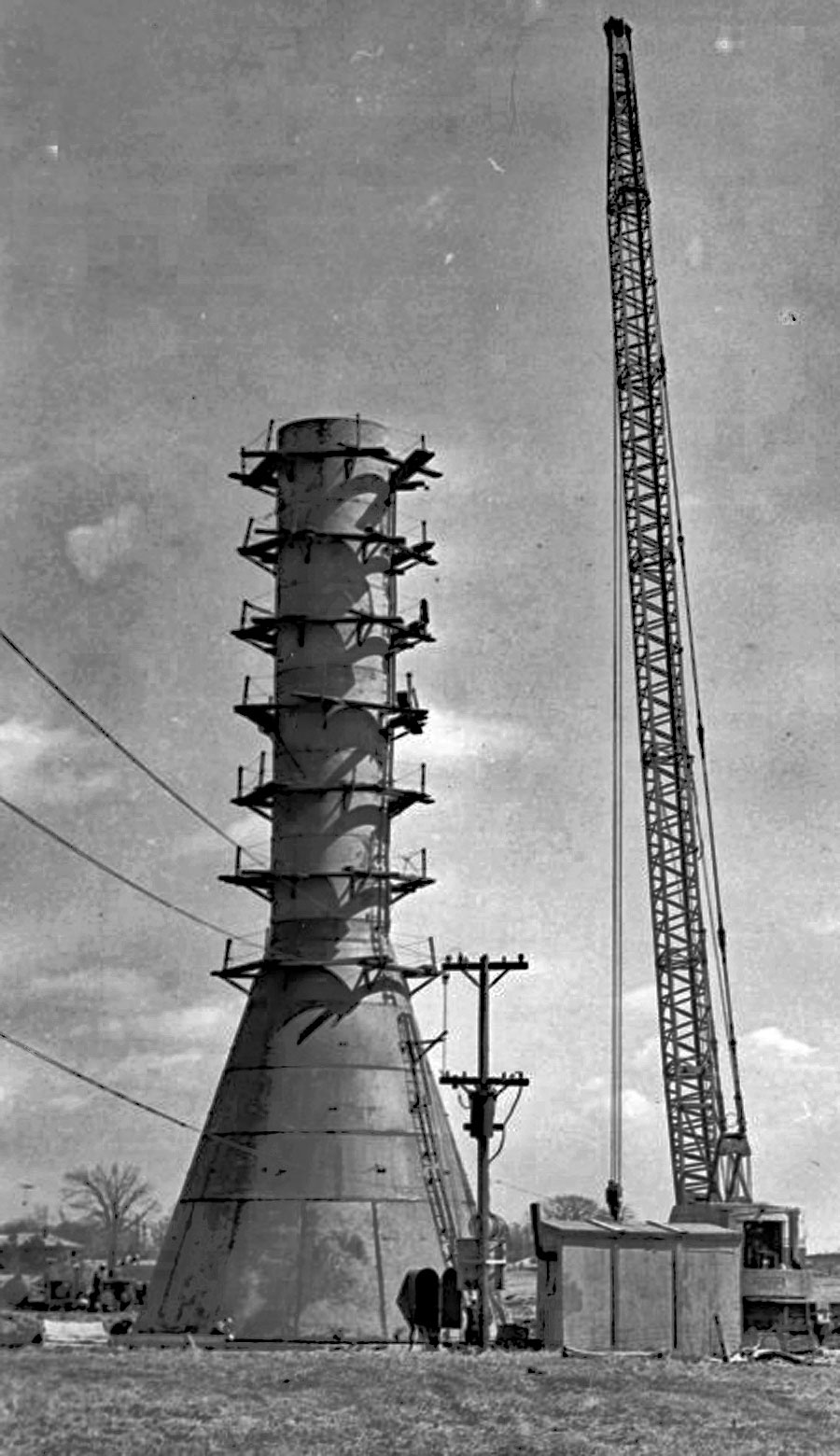

Artistic rendering of the icomm building in 1990. (photo courtesy of the Brant Historical Society)

The Icon, the aluminum tube sculpture that sits atop the Casino, formerly icomm. The sculpture, shown here at sunset, looks like a lower case i. It represents both a beacon and a receiver. It was designed by Canadian artist Ron Baird and his wife Linda. The inner portion is a 30 foot, 18-inch square structure housing 32 strobe lights. It was placed on 13-September-1989. It is surrounded by a 50 foot aluminum tube sculpture that was put in place in November 1989. The sculpture was installed by Taylor Construction. (photo by the author)

Businesses and organisations investigated the potential use of the facility over the next three years. Uses included a technology and media centre run by a consortium of colleges, a university, a college to study telecommunications, a telemarketing centre, and a television production facility.

In September 1994 a pending lease agreement was reached with Canadian Sportfishing Productions to move their production facilities into the building. The company encountered financial difficulties and withdrew their proposal.

A suggestion first proposed in 1992 was to convert the building into a casino. The province was studying allowing casino gambling in Ontario. When the icomm project was cancelled a Yes Casino for Brantford committee, spearheaded by Mike Tutt, began lobbying the provincial government to locate a casino in Brantford.

In 1994 Six Nations Band Council set up a gaming committee to study setting up an off-reserve casino in Brantford. In February 1995 Brantford City Council agreed to meet with Six Nations Band Council to discuss converting icomm into a native owned off-reserve casino. This idea did not progress further.

In 1996, the provincial government began to look for sites to establish a charity casino. Brantford was selected as one of 44 sites in 1997. Over the next few years, there was a pitched battle between those who wanted to see a casino located in Brantford and those who did not. Mayor Friel was not a supporter. The Expositor tried to measure the community’s feeling towards a casino through a write in campaign. The result of the vote was two to one against the casino. With that result, Council voted unanimously against hosting a casino. The Yes Casino for Brantford committee lobbied for a referendum during the 1997 municipal election. The referendum showed 55 percent of voters supported hosting a casino. Council changed its position on hosting a casino after this.

Logo of the Brantford Charity Casino, 1999. (photo by the author)

RPC Anchor Gaming was selected by the province to run the charity casinos. The company offered the City $4 million for the icomm building in February 1998. The anti casino forces continued to lobby City Council to overturn their decision going as far as appealing to the Ontario Municipal Board to quash the rezoning of the icomm property. In late 1998, the province decided not to create 44 casino sites but rather only four and to have them operated by the Ontario Lottery Corporation rather than RPC Anchor Gaming. The OLC picked up RPCs option on the icomm building in January 1999. OLC would spend $24 million to renovate the building.

City Council organised the Brantford Casino Impact Study to prepare for the opening; to measure the effects the casino would have on the City. The Casino held an opening gala on 17-November-1999 for 1,800 people. By February 2000, the casino was so busy it started to operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The expectation was that the casino would contribute $1.2 million dollars a year to the City as the City’s share of slot machine revenue. The casino’s first quarter revenue sharing cheque to the City was $1.5 million. It was the most financially successful of the four charity casinos in the province. The other charity casinos were in Sault Ste. Marie, Point Edward (Sarnia), and Gananoque. Attendance reached one million on 8-June-2000, just after 172 days of operation.

There was controversy on what to do with the casino money. After much deliberation, debate, and public outcry City Council decided to direct the money to a special fund used for capital projects and community investments. The money would not be used to reduce property taxes or other operational purposes.

Roads and Rails

The saga of the Brantford Southern Access Road continued into the 1990s. The roadway was conceived in the 1960s as a limited access highway that would loop though the southern portion of the City connecting West Brant with Highway 403. Only the portion of roadway between Mount Pleasant Street and Erie Avenue was completed by the early 1970s. Twenty years had passed, and the roadway was still largely a dream; a contentious dream. Concerns about the roadway included: ecosystem destruction, Native land claims, and a division of neighbourhoods as the road would cut through the City south of Colborne Street, across the Glebe lands, along the canal then along Greenwich Street, behind the homes along Eagle Avenue to meet up with the West Brant portion at Erie Avenue. These residents felt the need for the expressway was outdated. A need did exist, and still does today, to move traffic efficiently from the Wyndfield development in West Brant to Highway 403 to accommodate the new resident commuters. In 1992, the City commenced efforts to complete the roadway. It was at this time that the road was downsized to a 4-lane roadway from the original limited-access expressway. A provincial government report released in January 1993 called for the project to be put on hold so it could be re-evaluated and Native issues resolved.

A portion of the roadway construction was allowed to proceed, from Colborne Street to Henry Street. This portion opened in July 1996. There was community backlash with the proposed name of the new road, the Wayne Gretzky Parkway. There was an anti-Gretzky sentiment with a minority of residents. This generated negative publicity for the community, but the name ultimately prevailed. The parkway was extended to Dunsdon Street, again not without controversy and a call for more environmental studies. This portion was opened on 9-December-2000. The final northern portion to Powerline Road opened on 15-October-2001.

In 2000, the City accepted $11.5 million and all adjoining land next to the expressway from the provincial government in exchange for a release of any further responsibility by the provincial government to build or maintain the roadway. In November 2000, the agreement with Six Nations elected Band Council to build the BSAR through the Glebe lands expired and the Band Council chose not to extend or renegotiate the agreement.

Work on Highway 403 between Brantford and Ancaster began in the summer of 1990. The volume of traffic carried on Highway 2 between the two centres was heavy and hazardous given all the homes, businesses and farms located along the highway. The City and Chamber of Commerce continued to lobby the provincial government to complete the highway because the highway was vital to the City’s economy and growth. Highway 403 finally opened on 18-August-1997 to great fanfare. A street (highway) party was held on the roadway on 14-August-1997. The highway was finally completed between Woodstock and Hamilton 45 years after it was first conceived. Sound barriers on Highway 403 through the City began to be erected in 1991. The project was completed in 1997.

The Ring Road was renamed Icomm Drive on 5-October-1992.

In 1989, VIA Rail drastically reduced the number of trains travelling through and stopping in Brantford from thirteen to four. GO Transit studied service to Brantford but abandoned the idea because the distance between Aldershot and Brantford was too long with little potential for stops between Brantford and Aldershot due to a lack of population hubs. In 1991, the provincial government paid VIA a subsidy to resume its weekday morning commuter train from London to Toronto. The subsidy was part of a three-year trial. The service became permanent when ridership made the run profitable for VIA.

Arrival of the morning commuter train, Train 82, at the Brantford VIA Rail station. (photo by the author)

This post concludes my serialised History of the City of Brantford.